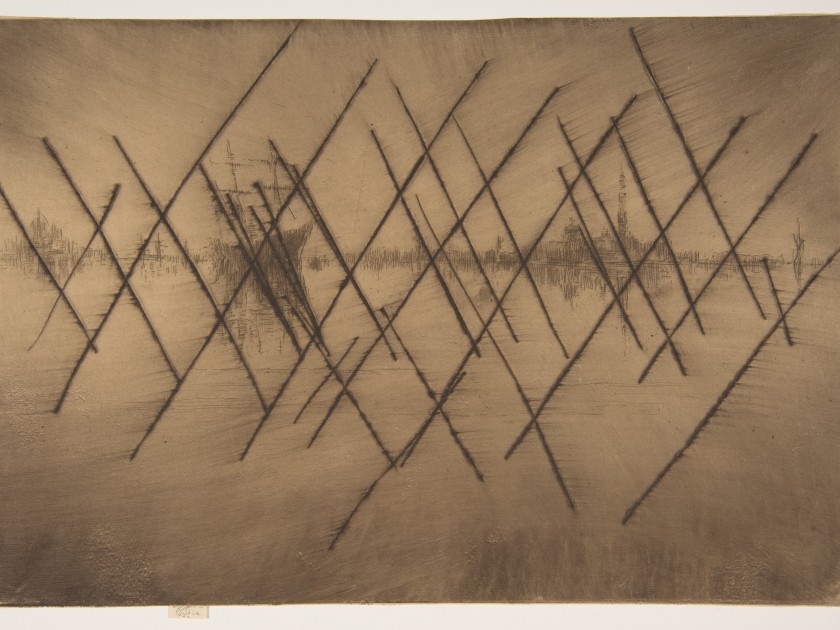

Nocturne, from First Venice Set (“Venice: Twelve Etchings,” 1880), James McNeill Whistler, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917.

The year 1492 is commonly associated with Christopher Columbus’ voyage to what has become known as the Americas. But in the history of European Jewry, this is the year which marks the Jews’ expulsion from Spain. In the records of Florence it marks the death of the great art patron Lorenzo ‘the Magnificent’ de’ Medici, while in Catholic history 1492 is the year that Rodrigo Borgia ascended to the papal throne. In short, it is a year that we now look back on as the beginning of upheaval in Europe and beyond. This conjunction of events is the starting point for my new book, The Beauty and the Terror. From the start of planning I was keen to include the story of Italy’s Jews, whether they came as refugees or had been long-standing residents.

The Renaissance is very often told as a positive story in the history of European Christendom. To this day, tour groups circulate through Italian galleries and churches to appreciate the wondrous art of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Yet the cultural elite who commissioned these works existed in a broader context, one characterised by warfare, persecution, and campaigns for church reform. Jewish history is entangled in this world, not least because this is the society that in 1516 created the Venetian ghetto.

Alexander VI — the newly-elected Borgia pope — allowed Jewish refugees to come from Spain to Italy. Born in the Spanish kingdom of Aragon, Alexander was labelled a marrano—a pejorative term for a converted Jew — and his son Cesare was called a “Jewish dog.” These tales of the Borgias were precursors to the later “Black Legend” of Spain, promoted by Protestant propagandists who used Spain’s long history of coexistence between Jews, Muslims, and Christians to imply that the nation was backward, superstitious and cruel, and might never be fully Christian.

The attitude of the Christian majority in the Italian states — Italy was not unified until the nineteenth century — was one of reluctant acceptance of Jews, amid periodic persecutions and expulsions. The Venetian ghetto offers an example of how those attitudes played out. The background to the ghetto’s creation was Venice’s defeat by the French at the bloody battle of Agnadello in 1509. In its aftermath numerous refugees fled Venice’s mainland territories for the safety of the island archipelago, and the law barring Jews from long-term residence in Venice was lifted. Wartime was conducive to exceptions to the rules.

Once the conflict eased, however, Christian preachers began to call for new restrictions, or even outright expulsion. The ghetto was a compromise, defended on the basis that Jewish moneylending was essential to Venice’s economy. Although the large banks of Italy were Christian-run (the interdict that Christians could not loan money was abandoned in the interests of profit), smaller loans were typically provided by Jewish lenders, on whom farmers and small businesses depended. As the sixteenth century went on, however, Catholic reformers promoted city-run pawnbrokers, known as the “monti di pietà” or “mounts of piety”, as a Christian alternative. One such bank, the Monte dei Paschi di Siena, is still in operation today.

The ghetto was a compromise, defended on the basis that Jewish moneylending was essential to Venice’s economy.

A few Jewish intellectuals made careers in Italy, among them Giuda Abarbanel, known as Leone Ebreo (meaning “Leo the Jew”). Originally from a high-ranking Portuguese family, he had been exiled first to Spain, and then to Naples and Genoa, where he wrote his Dialogues on Love, a text exploring the relationships of God, the universe, and human beings via the concept of cosmic love. Notable for its engagement with Jewish tradition, it was primarily received as a contribution to courtly literature, and Christian writers emphasized its Platonic and Aristotelian elements; it went through multiple editions and is quoted in Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

As the Catholic Church strove to emphasize its orthodoxy in the face of competition from Protestantism, Pope Paul III briefly expelled the Jews from Rome. They were readmitted but confined to a ghetto from 1555 under Paul IV, whose decree prohibited the construction of new synagogues and required Jews to wear a blue hat or other identifying marker. Paul IV was notorious for his hostility to Jews. He had encouraged the public burning of the Talmud in 1553, in an event timed to coincide with the Jewish New Year; he had also presided over a pogrom in the papal town of Ancona on the Adriatic coast. Further expulsions and ghettoization followed across the Italian states in the second half of the sixteenth century.

By weaving these different strands of Italian history together, we gain a richer and more complex image of the late Renaissance. It’s possible to spot, for example, the parallels in the Italian states’ treatment of prostitutes and Jews: both groups were required to wear identifying clothing; both were acknowledged to provide a socially-useful but stigmatised service (sex on the one hand, moneylending on the other).

These narratives, however, are often marginalized in popular histories of the Renaissance. To understand why we can look back at the long development of this history, both outside and within the academy. The Renaissance was constructed as a crowning moment for “western civilization;” it marked the revival of the best of the ancient world, after its loss during the Dark Ages, to be superseded only by the Enlightenment to come. That story tends to omit acts of persecution, enslavement, and other other less savory aspects of the Renaissance. On a holiday in Italy, or touring the Renaissance jewel-boxes, it’s always tempting to highlight the bright and spectacular instead of the uncomfortable. But we get a fuller, richer picture of the Renaissance when we also consider its less glorious side.

Catherine Fletcher is a historian of Renaissance and early modern Europe. She is the author The Beauty and the Terror: The Italian Renaissance and the Rise of the West, recently published by Oxford University Press, and of The Black Prince of Florence, also published by Oxford University Press and newly out in paperback. She teaches History at Manchester Metropolitan University in the UK and has held research fellowships in London, Florence, and Rome.