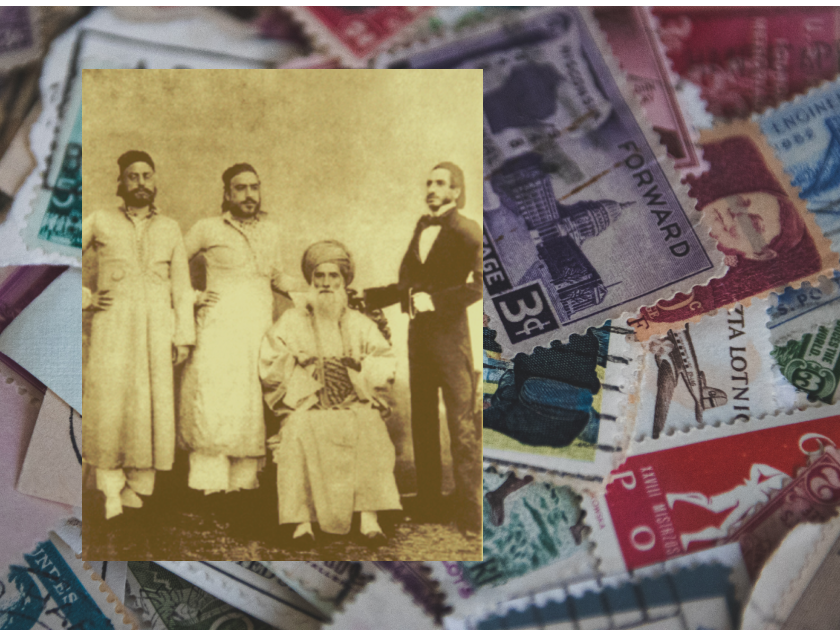

David Sassoon and Sons, edited, courtesy of the publisher

Through the darkened streets, the richest man in Baghdad fled for his life.

Just hours earlier, David Sassoon’s father had ransomed him from the jail where Baghdad’s Turkish rulers had imprisoned him, threatening to hang him if the family did not pay an exorbitant tax bill. Now a boat lay waiting to take thirty-seven-year-old David to safety. He tied a money belt around his waist and donned a cloak. Servants had sewn pearls inside the lining. “Only his eyes showed between the turban and a high-muffled cloak as he slipped through the gates of the city where generations of his kin had once been honored,” a family historian wrote. It was 1829. His family had lived in Baghdad as virtual royalty for more than eight hundred years.

For more than a thousand years, Jews had flourished in Baghdad, known in the Bible as Babylon. When Europe was mired in the darkness of the Middle Ages, Baghdad was one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world. It was home to some of the world’s leading mathematicians, theologians, poets, and doctors. Within this world, Jews flourished. They first arrived in 587 b.c., when Babylon’s King Nebuchadnezzar laid siege to Jerusalem, and upon victory carried 10,000 Jewish artisans, scholars, and leaders-Judaism’s best and brightest-to Baghdad into what the Bible dubbed “the Babylonian Captivity.” The book of Psalms famously documented the despair of these displaced Jews:

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down

Yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.

In fact, “the Babylonian Captivity” changed the course of Jewish history. Jewish learning and religious innovation blossomed, giving Jews the religious, political, and economic tools-and a way of thinking-they would use to survive and thrive around the world over the next millennia and through to today. It marked the start of the Jewish diaspora: the dispersal-and survival-of Jews around the world, even when they made up just a small sliver of the population. When the Persians conquered Baghdad and offered the Jews the chance to return to Jerusalem, only a few accepted. Most decided to stay. Baghdad’s Jews considered themselves the Jewish aristocracy.

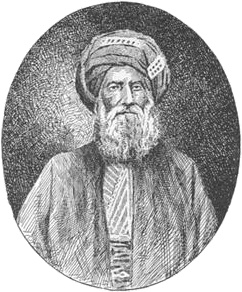

David Sassoon, courtesy of the publisher

Presiding over this dynamic, self-confident community-leading it and nurturing it-loomed the Sassoons. Trading gold and silk, spices and wool across the Middle East, the Sassoons became Baghdad’s richest merchants. Starting in the late 1700s, the Ottoman Turks appointed the leader of the Sassoon family as “Nasi,” or “Prince of the Jews”-their intermediary in dealing with Baghdad’s influential Jewish population.

Preserved among the Sassoon family papers are memoranda in Turkish and Arabic that testify to the sweep of the Nasi’s power. The Nasi Sassoon negotiated loans, planned budgets, devised and collected new taxes. He was the de facto secretary of the treasury, charged with building a modern financial system. When the Nasi traveled to meet Baghdad’s Turkish ruler at the royal palace, he was carried on a throne through the streets; Jews and non-Jews alike respectfully bowed their heads.

Starting in the late 1700s, the Ottoman Turks appointed the leader of the Sassoon family as “Nasi,” or “Prince of the Jews”-their intermediary in dealing with Baghdad’s influential Jewish population.

Buoyed by these connections, the Sassoons built a multinational economic empire that extended from Baghdad across the Persian Gulf and Asia. Merchants from across the Middle East and from India and China passed through the Nasi’s luxurious home and compound. They lounged in his walled courtyard, shaded by orange trees, to escape the 120-degree heat. Underground storerooms held the family’s gold.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as their wealth and fortune expanded, the Sassoons became accustomed to business allies and rivals calling them “the Rothschilds of Asia” for the rapid way their wealth and influence spread across China, India, and Europe. But privately they considered the comparison misleading-and a little demeaning. In the Sassoons’ minds, the Rothschilds were arrivistes‑a poor family that in one generation had leapt from the ghettos of Europe to business prominence and political influence. The Sassoons may have been unknown to the Chinese emperor, the Indian raj, or the British royal family, but they had been rich, prominent, and powerful for centuries.

David Sassoon was born in 1792 and trained from childhood to become the future Nasi. He was a business prodigy with an extraordinary gift for languages. At thirteen, he started accompanying his father to the “counting houses”-the forerunners of banks and accounting firms-where the Sassoon revenues were calculated. He was tutored at home in Hebrew (the language of religion), Turkish (the language of government), Arabic (the language of Baghdad), and Persian (the language of Middle Eastern trade). Six feet tall, David stood head and shoulders over his family and the people he would one day lead.

As David was preparing to assume his vaunted role as Nasi, the comfortable position the Sassoons and the Jews of Baghdad had enjoyed for centuries collapsed. A power struggle among the Ottoman rulers of Baghdad put a faction hostile to the Jews in power. Desperate for money to boost a collapsing economy, the Turks began harassing and imprisoning the Sassoons and other wealthy Jews, demanding ransom. David sought the help of the Turkish sultan in Constantinople on behalf of the Jews and Sassoons of Baghdad, accusing the city’s rulers of corruption. But he was wrong to put his trust in the imperial government, and word quickly reached Baghdad of his betrayal. He was arrested; the Turkish pasha ordered him hanged unless the family paid for his release. Taking matters into his own hands, his elderly father bribed his son out of prison, hustled him through the city in disguise, and chartered a boat to get him to safety.

David left Baghdad in a state of rage and helplessness. He had just remarried following the death of his first wife of twenty-five years. He was abandoning his new bride and his children. All the glory of the Sassoons, their wealth and position, had been promised to him and was now snatched away. As the ship sailed away, he turned toward the disappearing shore and wept.

It was an exodus that would eventually lead the family to Shanghai, and to unrivalled wealth and influence

From The Last Kings of Shanghai: The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China by Jonathan Kaufman, published by Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Claimant.

Jonathan Kaufman is a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who has written and reported on China for thirty years for The Boston Globe, where he covered the 1989 massacre in Tiananmen Square; The Wall Street Journal, where he served as China bureau chief from 2002 to 2005; and Bloomberg News. He is the author of A Hole in the Heart of the World: Being Jewish in Eastern Europe and Broken Alliance: The Turbulent Times Between Blacks and Jews in America, winner of a National Jewish Book Award. He is the director of the School of Journalism at Northeastern University in Boston.