Photo from The Adventures of K’ton Ton by Sadie Rose Weilerstein

The author of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) by tradition considered to be King Solomon, comments bitterly that there is nothing new under the sun. But for young children the world’s cyclical nature is deeply reassuring. Nothing in the Jewish year emphasizes this sense of permanence and consistency more than the celebration of Rosh Hashanah. Two modern classics, one from the mid-twentieth century and the other towards that century’s end, each reflect the Jewish emphasis on starting over with a new beginning within the stable core of tradition. Jane Breskin Zalben’s Happy New Year, Beni (1993) and Sadie Rose Weilerstein’s What the Moon Brought (1942) have a permanent place in the canon of Jewish children’s holiday literature. Zalben’s gorgeously illustrated tale of bears observing Rosh Hashanah presents the holiday with tenderness and humor, while Weilerstein’s earlier book places two lively sisters within Jewish American life at a key moment in history, during World War II. Both books emphasize the indelible role of festive meals, and both have at their core a quality of lasting beauty and sensitivity to what the arrival of Rosh Hashanah means each year.

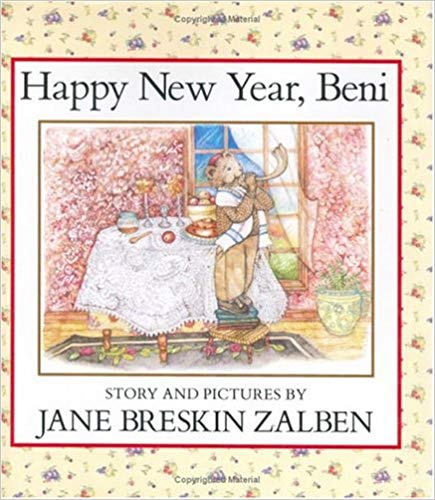

Happy New Year, Beni takes place in an unspecified era, one deliberately designed for its enduring appeal to both the central importance of family and to classical styles of illustration. The book’s setting is clearly meant to be a mixture of timeless and contemporary; where the family finds itself on the spectrum of observance is not so important. Beni wears a kippah and his sister Sara wears a blue and white dress, ankle socks, and Mary jane shoes — which could have been part of a girl’s wardrobe from the nineteen-fifties as well as the nineties. Grandpa wears a three-piece suit and Grandma blesses the candles wearing a delicate veil. The family car is a vintage model. Even the children’s names evoke the nostalgia of Jewish roots: Max, Rosie, Goldie, Molly, and Sam, all ones which had recently returned to popularity when the book was written. Beni and Sara prepare favorite foods with their parents, bringing rugelach, mandelbrot, and strudel to their grandparents’ house. Using watercolor on parchment, Zalben’s intense colors and exquisite detail draw children into the scenes, with every raisin on the challah and each slice of pomegranate evidence that this family is as real as their own — even if they are bears.

Another nostalgic, but still relevant, aspect of the book is that Beni’s grandparents are a vital part of his life, links in a generational chain which has always been central to Jewish tradition. Grandma distributes figs and dates to the children and Beni’s cousin Max eats more than his share, prompting Mama to mistakenly accuse Beni of overeating. Grandma looks serene while Mama frowns and places her hands on her hips, the universal pose of maternal annoyance. Papa has the honor of blowing the shofar in synagogue, but it is Grandpa who takes the children to participate in the ritual of tashlikh, explaining to them that throwing pieces of bread into running water symbolizes the need to unburden themselves of bad deeds. Grandpa’s words are simple and nonjudgmental as he verbally meets his grandson at a child’s level: “We get rid of what we did during the year that wasn’t so nice and we begin with a new, clean slate.” Anything Beni did wrong could have been no worse than “not so nice,” and even the quaintly dated metaphor of a clean slate, no longer used in schools for writing, is a sign from the past.

Another nostalgic, but still relevant, aspect of the book is that Beni’s grandparents are a vital part of his life, links in a generational chain which has always been central to Jewish tradition.

By the 1990s, Jewish life in America was rapidly changing. Many Jews had begun to challenge gender roles in rituals, intermarriage had become common, and the unquestioned norm of two-parent nuclear families was being challenged. Yet these significant new realities are peripheral to Beni’s New Year, where family life is central to preserving the essentials of Jewish identity. In Beni’s tashlikh with his grandfather, Zalben alludes to this continuity of identity in a memorable sequence of words: “Beni remembered his mistakes. He took a small crust of bread from the palm of Grandpa’s hand, tossed it into the brook, and watched it go downstream.” The image of Beni accepting the small piece of bread from the center of his grandfather’s hand, and then letting it go, expresses how the new year will both include and let go of the old one.

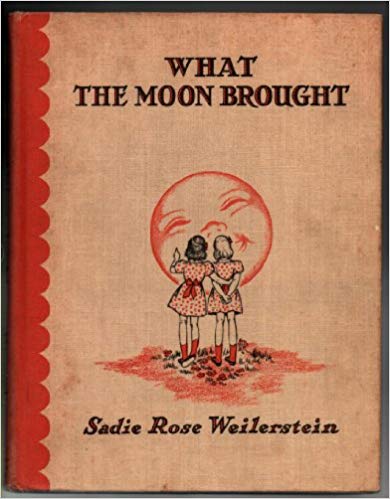

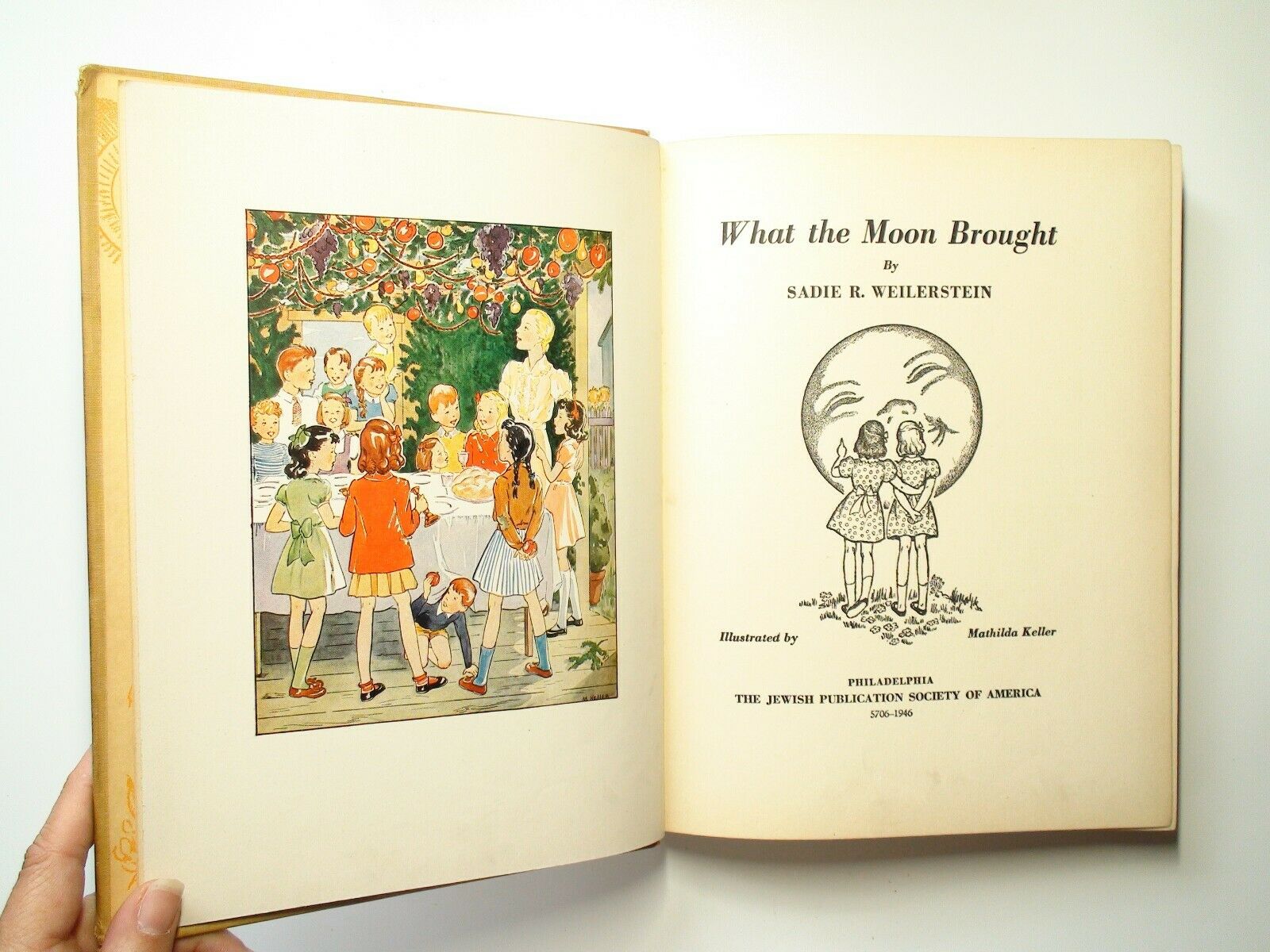

Sadie Rose Weilerstein’s What the Moon Brought is less known today than Weilerstein’s series of stories about K’ton Ton — the adventures of a fantastically small boy exploring the normally scaled setting of rituals and holidays. At first glance, this book may seem to be an artifact of a long-gone era, yet its roots in an earlier time reinforce the message that core aspects of Jewish life are resilient, not compromised by the inevitable changes of history. The original 1942 version was reprinted in 1968, with a new introduction by the author headed “Dear Boys and Girls,” concluding with “Shalom (peace) to you.” Weilerstein adopts a kindly didactic tone to confirm that the world has changed since 1942, but the Jewish year is still as round as ever: “The children who first read What the Moon Brought are now grownups…Astronauts are preparing to land on the moon. BUT Ruth and Debby are still little sisters…”

Time stands still in the world of books and a new generation of readers will still experience a sense of Jewish time, the cyclical nature of the calendar and the year, much as Ruth and Debby did, in spite of both wrenching and triumphant events for Jews that have taken place in the interim. There is no reference to the near-annihilation of European Jewry which was taking place while the original book first appeared, although Weilerstein does explain that Debby and Ruth refer to Israel as Palestine because when they “first stepped into the book away back in 1942,” and that was the land’s name.

While Beni is much more excited about the actual practices of Rosh Hashanah, Debby and Ruth are curious about the holiday’s origins. As Americans, they are familiar with celebrating the birthdays of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln but the concept of the world’s age is challenging. When their mother explains that it is “more than five thousand years old,” they decide that only a really big and round birthday cake will be adequate to commemorate that unimaginable span of time. Weilerstein incorporates verse into her narrative, and the sisters recite it as a kind of invented children’s liturgy, Ruth taking the part about newness — including new shoes, dresses, and ribbons — while Debby chants that everything is also a circle, “The apples are round,/And the cakes are round,/and the hallahs are round!/Everything is ROUND on Rosh Hashanah/For a good ROUND year.”

As Americans, they are familiar with celebrating the birthdays of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln but the concept of the world’s age is challenging.

Here food is more orderly and contained, unlike its unquestioned abundance in Happy New Year, Beni. Illustrator Mathilda Keller’s shaded black and white image of Debby and Ruth’s holiday table shows a round bowl of apples at the center, as Father raises his kiddush cup and Mother and the girls solemnly lower their heads. No one is kicking one another under the table, as Max and Beni do. Father uses a food metaphor to explain to the girls that their suggested birthday cake for the world would have to be bigger than all the wheat fields, all the scythes, all the mills, all the mixing bowls, and all the ovens they could imagine. This chain of production emphasizes that food does not arrive on their table out of nowhere, not even through their grandparents’ generosity, but is the result of resources and labor. The natural world is an essential part of their understanding of Rosh Hashanah, although the ritual of tashlikh is left unmentioned. Instead, the family leaves their house and goes outdoors, “way past their bedtime,” in order to find candles for the world’s birthday, in the form of an evening sky “dark and velvety — and…filled with stars.” Weilerstein conveys that this moment is as deeply reverent as any of the holiday’s prescribed ceremonies as “Ruth and Debby threw back their heads and raised their eyes to the sky,” seeing in the new moon of the month of Tishri “a silver cradle,” and witnessing the birth of the year.

A second Rosh Hashanah chapter in Weilerstein’s book adds an environmental narrative as backstory, when Ruth and Debby travel by car, train, boat, and taxi to visit their grandparents and aunt, whose garden is dying of thirst due to lack of rain. No rain, no flowers. No flowers, no nectar. No nectar, no honey. No honey, no Rosh Hashanah treat. Debby and Ruth’s kindness to the environment transforms this near-disaster into a Garden of Eden. A bee, redundantly named Devorah, (Hebrew for “bee,”) is thrilled when visitors from the city intervene to rescue her hive with watering cans. Here Weilerstein turns from everyday life to fable, allowing the two girls a crucial role in ushering in the new year. The bees are able to generate so much honey that they call a meeting to decide how to use the surplus, agreeing to send it to Ruth and Debby to sweeten their holiday. In Happy New Year, Beni, food is constantly available without questioning its source, whereas in What the Moon Brought, the bees decided best way to distribute the limited fruits of the land.

Happy New Year, Beni portrays a Rosh Hashanah among supportive family, with plentiful food, quiet reflection about making the new year better than the last one, and grandparents sharing wisdom in an unobtrusive and nonjudgmental way with a new generation. Zalben’s bears remind us that the Jewish world is round and complete each year, yet also open to improvements which they have the power to initiate with the help of those older and wiser. What the Moon Brought brings readers back to a more vulnerable era for Jewish Americans, when their hyphenated identity was only beginning to feel secure, and as the impending assault on their brothers and sisters in Europe would make commitment to Jewish continuity even more urgent. Whether children today live within the same extended families or different and newly accepted configurations of Jewish life, both books have value beyond nostalgia. Zalben and Weilerstein recognize that children need to see their own role in the creation of a new year, one where personal relationships, as well as the natural world, begin again.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.