On December 25th, many Jews will observe their annual movie-going ritual with Wonder Woman 1984, whose Christmas Day premiere is set to take place simultaneously in theaters and on HBO Max. Long thought to be the rare comic book superhero without a Jewish creation myth, Wonder Woman, as it turns out, can trace her roots to the work of Miriam Michelson, a Jewish American writer and suffragist who harnessed the power of popular culture in the early twentieth-century fight for women’s rights.

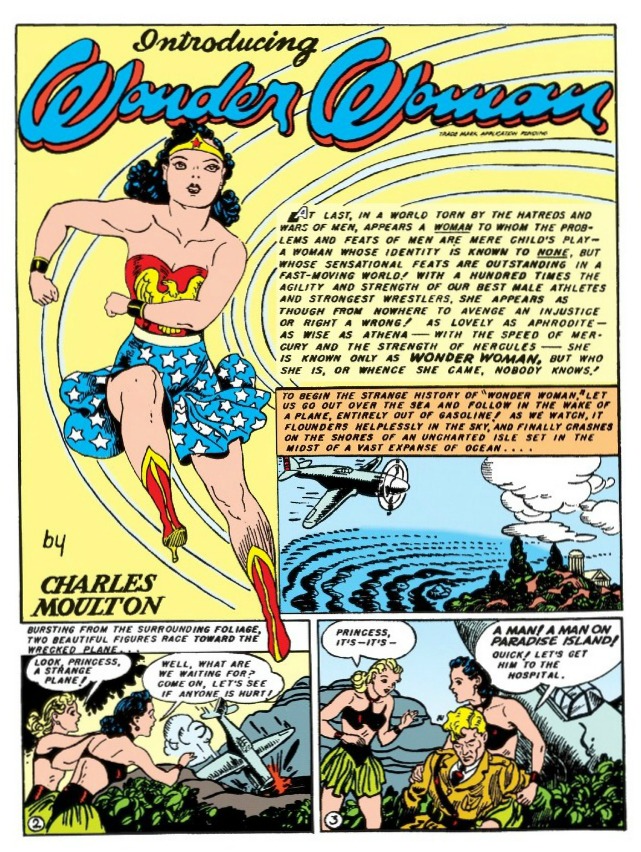

The character of Wonder Woman, who debuted in 1941 in All Star Comics #8, was the creation of an eccentric man, William Moulton Marston (who published the comic under a pen name, Charles Moulton). But her origins, as Jill Lepore has shown in The Secret History of Wonder Woman, lie in the suffrage movement. Paradise Island, the civilization of Amazonian warriors to which Wonder Woman belongs, was inspired by tropes of feminist utopian fiction; this genre reached its zenith in the decades leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

Miriam Michelson, courtesy of the author

In 1912, Michelson, a bestselling author of popular fiction, published The Superwoman, a feminist fantasy narrative about a matrilineal island society in which women rule by “mother right.” Like many of the suffrage activists who took to the streets and took up pens, Michelson was a real-life Wonder Woman. Born in 1870 in California to Jewish Polish immigrants, Michelson became a celebrity reporter in the 1890s, breaking gender barriers in the newsroom as one of the first women to cover crime, politics, and sports for San Francisco’s top daily newspapers.

By the early twentieth century, she had achieved national fame as a novelist, a vocation that proved more lucrative than journalism for a single, independent woman supporting herself and members of her large extended family. Her celebrity as a novelist and trailblazing journalist gave her a public platform, which she subsequently used to champion a variety of progressive causes — including suffrage.

When Michelson wrote The Superwoman, she was fresh off a speaking tour for the successful suffrage campaign that won women in California the right to vote in 1911. Appearing as the lead novella in the popular magazine The Smart Set, this feminist utopian narrative is, in part, a celebration of women’s newly acquired political power. As a work of speculative fiction, it can also be seen as a call to action, a reminder that women’s battles for equal rights were far from over.

The story’s protagonist, Hugh Ellinwood Welburn, is an insufferably arrogant bachelor. We first meet him on an ocean-liner where he is choosing which female passenger it will be most advantageous to marry — a decision he plans to finalize by flipping a coin. Pointedly referred to by his initials, H.E. is a representative of Gilded Age patriarchal society.

By the end of the novella’s first chapter, Welburn is swept overboard by a storm. He awakes on a remote, unnamed island; his life has been saved by one of its powerful female inhabitants. This scene is echoed on the first page of Wonder Woman’s comic book debut, when a “beautiful figure” rescues Steve Trevor after his plane crashes on Paradise Island, setting in motion her transformation into Wonder Woman.

Like many of the suffrage activists who took to the streets and took up pens, Michelson was a real-life Wonder Woman.

The arrival of a man has no such transformative effect on Michelson’s superwomen, who view their island’s male population as second-class citizens, tolerated because they serve reproductive and domestic functions. Instead, the women intend to transform Welburn, acclimating him to the new land by schooling him in their tongue and in the ways of the “matriarchate.” In the world of The Superwoman, not only are traditional gender roles flipped, but women are revered for their wisdom, their physical strength, and their maternity. The birth of a girl, for example, occasions community-wide jubilation. Welburn learns of the social norm of polyandry when the superwoman who chooses him as her mate plans to take another husband.

Welburn’s tales of his home in America are met with mocking disbelief. “Would you pretend that in your topsy-turvy country descent is through the father? Does the man there bear the child?” asks the Mother Goddess when Welburn dares to suggest that the daughter he fathered should carry his name. The Mother Goddess “laughed heartily” at the absurdity of the idea, “while the women about her gave way to immoderate laughter.” Through humor, Michelson exposes the illogic of patriarchy. The Superwoman reads more as an adventure tale than a polemic, thanks to Michelson’s skill at cloaking her feminist message in comedy and genre fiction.

Wonder Woman’s debut in All Star Comics #8 (December 1941-January 1942)

Michelson’s first novel, In the Bishop’s Carriage, introduced a new type of hero for the picaresque (a genre of fiction that typically follows the episodic adventures of a low-born male protagonist). With a female pickpocket as its unlikely but appealing first-person protagonist, Michelson’s debut novel became a scandalous sensation when it appeared in 1904. The heroine, Nance Olden, was a prototype for the flapper and a fixture of popular culture for well over a decade, as the novel was adapted into a play and two films. The first film, which was released in 1913, starred silent film star Mary Pickford in her feature debut as the “girl thief.” By casting a woman as a rogue, a role previously reserved for men in fiction, Michelson hit on a formula for pleasurably diverting her audience while exploring women’s expanding role in the political and economic life of the nation.

At a time when women were loudly demanding the vote, Michelson’s fiction gave modern women a voice — one that was sassy, slangy, and (in the words of a book reviewer) as “‘catchy’ as ragtime.” A Yellow Journalist, a series of stories that Michelson published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1905, was loosely based on the author’s own journalistic exploits. Featuring a fearless “girl reporter” named Rhoda Massey, Michelson’s breezy, fast-paced prose captures the experiences of an ambitious woman in a male-dominated profession. Imagine Superman with Lois Lane’s boyfriend relegated to the sidelines, and Lois’s adventures as a reporter taking center stage.

In 1972, recalling her childhood encounters with the Wonder Woman comics, Gloria Steinem recognized the power of popular culture to bring about social change. She described how her qualms about the comic books’ contradictions and inconsistences — from the superheroine’s overly sexualized get-up, to alter ego Diana Prince’s submissiveness towards her conventional love interest — “paled beside the relief, the sweet vengeance, the toe-wriggling pleasure of … a woman who was strong, beautiful, courageous, and a fighter for social justice.” Watching Israeli actor Gal Gadot bring Wonder Woman to life on the screen is likely to elicit similar mixed feelings from feminist viewers. The pleasures, however, may be further enhanced by knowledge of real-life social justice warriors like Michelson who embraced pop feminism as a tool in the ongoing battle for gender equality.