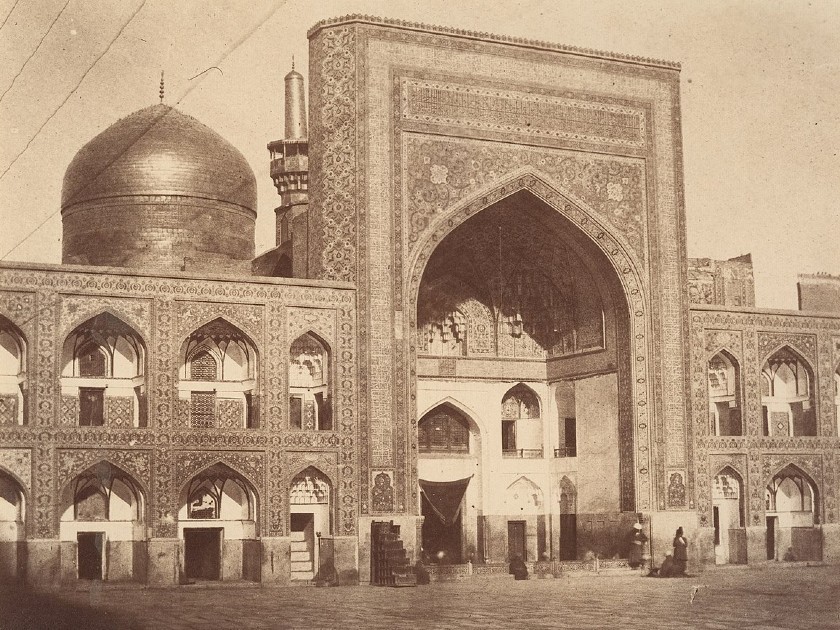

Main Gate of Imam Riza, Mashhad, Iran, Photograph by Luigi Pesce, 1850s

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Charles K. and Irma B. Wilkinson, 1977

My Iranian mother and I were on the subway when she noticed a group of bare-armed teens flaunting their tattooed biceps. “Jinko-lo-vinski!” she belted out.

These teenagers looked at her blankly, certain she was speaking a foreign tongue. In fact, “jinko-lo-vinski” was her best attempt at “Juvenile delinquents!” Mom was convinced her scolding words would cause them shame and result in social reform. Thanks to her indecipherable English, there was no altercation. They understood her as little as she understood them.

When Mom was lying flat on her back in a hospital recovery room after heart surgery, a nurse cornered me in the hallway. “What’s ‘meer-gah-zab’? Your mamma’s screaming it in my face: ‘Meer-gah-zab!’ And she’s insisting on having a private room. I told her, ‘Honey, this isn’t a five-star hotel. You’re in an ICU!’”

Feigning ignorance, I shook my head, pretending that meergahzab was pure gibberish. The alternative would have been to give the nurse the English translation: “TYRANT.”

It wasn’t just Mom’s words, but her entire world, that was often lost in translation. Born in 1925 in Iran, Mom had lived as an underground Jew in the fanatically religious city of Mashhad, a Shi’ite stronghold and pilgrimage site with a long history of maiming and massacring infidels. Head bent as she breathed through a black chador and peered through its eyeslits, she slunk through alleyways passing as Muslim. My father also relied on duplicity in order to survive, kneeling and bowing in public squares, reciting the Koran, and chanting namaz, while inwardly praying to HaShem, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Mom and Pop lived concealed, secretive lives, and were in constant fear of being outed.

Located in northeast Iran, close to the borders of Turkmenistan and Afghanistan, Mashhad was a major oasis on the ancient Silk Road and grew into an important center of industry and trade. The Persian king Nader Shah brought the first Jewish families from the Iranian city of Qazvin to Mashhad in the eighteenth century. After his assassination in 1747, antisemitism in Mashhad ran rampant, preparing the ground for a mob attack on the Jewish community in 1839 that left hundreds wounded and dozens dead. Survivors were given a choice: convert to Islam or die. My parents, descendants of these survivors, were observant Jews who pretended they had converted. Fathers protected their daughters from potential Muslim suitors by marrying them off within the Jewish community as soon as possible. My father’s mother, at the tender age of nine, was married to my grandfather who was twenty years her senior, though they didn’t have relations until she was twelve. My own mother was not yet fourteen when she was forced to marry my thirty-four-year-old father.

It wasn’t just Mom’s words, but her entire world, that was often lost in translation. Born in 1925 in Iran, Mom had lived as an underground Jew in the fanatically religious city of Mashhad.

In 1947, when my father immigrated with my mother and two older brothers to the United States, he was horrified by what he saw. Women in three-piece suits, heading for work, tightly pressed against men in crowded subway cars; women publicly smoking cigarettes and cursing with abandon. Pop called this nation “the wild west,” and whenever he uttered the word “freedom,” it was voiced as a curse. Through his Persian lens, America was a land of reckless, ruthless heathens that turned women into men, and fully championed sexual promiscuity.

As a child-translator growing up in Kew Gardens, Queens, I took my job seriously. It was up to me, I told myself, to accompany Mom as she grocery shopped and read her the ingredients on packaged foods. Whenever I was ill, it was up to me to translate into Farsi Dr. Horowitz’s directives as to how my mother should nurse me back to health. And at the age of three, I decided it was up to me to teach my mother to read, since she had never been allowed to learn in Mashhad.

I also took it upon myself to try to alter my father’s thinking, offering him measured and thoughtful reasons to embrace the outside world, not fear it, as he did in Iran. The kitchen phone ringing, a knock on our front door, sent him into a wild panic. I wanted him to trust all that was foreign, including me — his Jewish American daughter raised in Queens.

I failed.

More than anything, I longed to be seen and known as American, without any trace of henna, scent of rose water, or sound of Farsi. But Pop’s disdain for and distrust of this new country butted heads with the all-American girl I wanted to be. How could I explain to school friends my father’s ironclad belief that girls shouldn’t learn to read? How could I make his deep-seated reverence for silence and his wish to ban speech intelligible to them? Pop would tell my friends I wasn’t home even when I was, slamming the door to the Western world and anyone who came from it. He even went on a ten-day, suicidal hunger strike when I was about to move into a Barnard College dorm.

Translating English into Farsi left too much room for misunderstanding. Nuanced meanings differed, lifestyle and social values differed, background history differed. While “chickpeas” was a word I could easily translate into Farsi for Mom, there was so much that was untranslatable. As my parents’ personal interpreter, I stood between two nations, unable to bridge East and West. And as a first generation American, I couldn’t connect my New York City life and its limitless options with the underground, crypto-Jewish life they had led in Mashhad. Living in translation left me standing in a no-man’s land. Among Iranians, I felt like a fraud. In the company of non-Persian Americans, couplets from Ferdowsi’s epic, Shahnameh, and Rumi’s mystical verses thrummed through me. Caught between two sparring spirits, the ground beneath my feet kept shifting, throwing me off balance.

But over the years, this grey zone became my natural state. One I began to value.

Esther Amini is a writer, painter, and psychoanalytic psychotherapist in private practice. She is the author of the highly acclaimed memoir Concealed—Memoir of a Jewish Iranian Daughter Caught Between the Chador and America, and her short stories have appeared in Elle, Lilith, Tablet, The Jewish Week, Barnard Magazine, TK University’s Inscape Literary, and Proximity. She was named one of Aspen Words’ two best-emerging memoirists and awarded its Emerging Writer Fellowship in 2016. Her pieces have been performed by Jewish Women’s Theatre in Los Angeles and in Manhattan and she was chosen by JWT as their Artist-in-Residence in 2019.