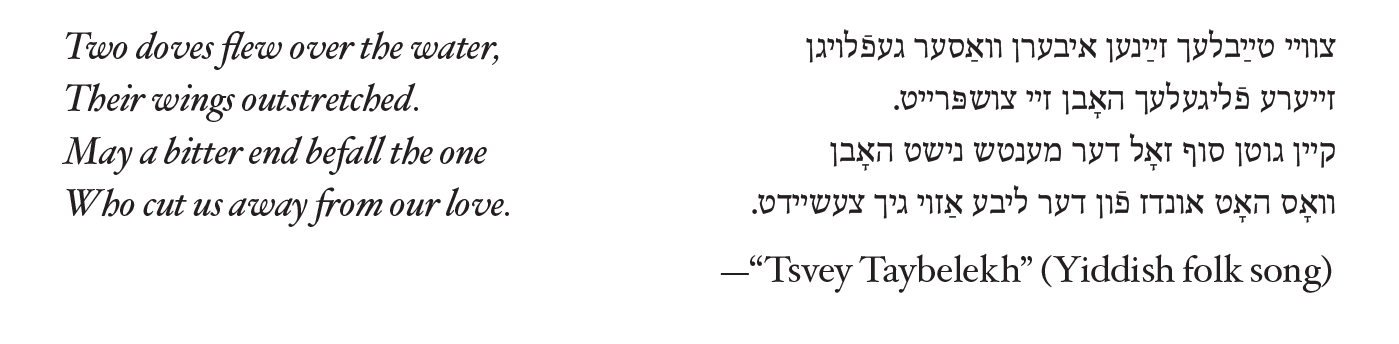

Illustration by Laura Junger (cropped)

Who can know what children will remember?

Who can know what folklore, what curiosities, what gruesome, fantastic stories will lodge in their heads? The sponge of a child’s brain sometimes absorbs more than it should — things adults might dismiss as insignificant or too complicated, or tales they might assume will lose their sharp edges as the gray world of labor settles in. It’s good for children to grow up in worlds rich with mystery. Parents should make sure their children hear plenty of tall tales — as many as possible — and hope at least a few of them stick.

Hinda remembered many things from her early years, but a few most intensely. She remembered, each time with a shudder, a story her uncle once told: One night, he’d found himself alone in the woods, hunted by a wolf. He pulled up his trouser leg to show her how the beast had mauled him before he killed it with only a pocketknife. She remembered the knotted white scar on his mangled leg. She remembered most of the stories and songs that the wandering scholars would teach when they passed through her village. And she remembered being eight years old, sitting on the floor as her grandmother peeled leaves off a head of cabbage, inspected each one closely for bugs, and talked about how souls float in water.

“That’s why, Hinda, you mustn’t drink from an uncovered glass of water on the Sabbath. On that one day, the spirits of dead sinners are spared the flames and tortures of Gehenna. The angels permit them to return to this world and cool themselves in standing water for twenty-five hours, between candle lighting and the emergence of three stars in the sky the next evening. So don’t be careless, Hinda. It would be very bad if, God forbid, you were to accidentally swallow another person’s soul. Can you imagine what might happen then?”

Hinda could. She imagined thousands of souls rising from the ground on the Sabbath, flying through the air with skin blistered and hair scorched from the hellfire, then one or two diving into a glass of water carelessly left out. She imagined drinking the water, and the souls flailing their way down her throat. And then what? Would the angels of destruction come at sundown to chase the souls back beneath the earth? In the confusion, would the angels get all mixed up and sweep her own soul off to Gehenna, leaving her body in the care of a stranger, a dybbuk?

Illustration by Laura Junger

Hinda slept in her grandmother’s bed that night. Her tongue felt dry and sandy in her mouth.

______

Hinda’s best friend in the world was Basya, the fruit seller’s daughter. Ever since she’d been little, Hinda had followed Basya around the market while her own mother sold mushrooms. Basya was two years older, and as soon as Hinda was old enough to be interesting to play with, the pair were inseparable, spending almost every day together. They always did what Basya wanted, because she had the best ideas. Basya was best at climbing trees, catching tiny river crabs, and building houses made of rocks and thatched with pine needles. She was best at braiding Hinda’s hair, which, even though it was bushy and unlucky red in color, looked good when Basya was the one taming it — and only then. But what really impressed Hinda was that Basya knew absolutely everything. Because Basya was often overlooked as the youngest of her seven sisters, she heard a great deal, and turned every scrap of gossip into a delicious story for Hinda. One day, eager to share a story of her own, Hinda told Basya about how souls bask in water on the Sabbath.

Basya knit her sharp eyebrows. “That can’t be true. I’ve never seen a soul in water. Do you even know what they look like?”

“No,” said Hinda.

“My mother says she saw her father’s soul when he breathed it out and died,” Basya said. “She says his soul was little, and made of golden light. It wiggled right out of his mouth and up through an open window, like a moth. Or a fish. Or a little snake!” She hissed and tickled Hinda, who screamed with laughter.

“My mother believes in all kinds of superstitions and old wives’ tales. She’ll fall for anything. Me, I’ll believe it when I see it,” added Basya, tilting her chin in the air.

Hinda was delighted to know something Basya didn’t. She formulated a plan.

______

Just before the Sabbath, Hinda stole an empty medicine bottle from her grandmother’s bedside, uncorked it, and filled it with water. She stood it up under her bed, and lay on the mattress stone-still, listening to every creak and groan of the house, afraid to fall asleep and miss the arrival of a visiting soul. But then, what if the soul saw her waiting and didn’t come? What if she hadn’t put out enough water? What if none of it was true, after all? She drifted off after midnight but woke before dawn, stirred by a weak glimmer emanating from under the bed. Clutching the cork in her fist, she peered down over the edge of the bed— and saw something soft and beautiful drifting in the water, like the afterimage of a candle flame. She seized the bottle and slammed in the cork, sloshing the water inside. Frightened by her own boldness, she carefully put the bottle back down, and retreated to the middle of her bed. She waited there, sleepless, until her mother called her for breakfast, and she went about her Sabbath day too afraid to look at the soul. The light was long in the afternoon when she built up the courage to kneel down and peek under the bed again.

Clutching the cork in her fist, she peered down over the edge of the bed— and saw something soft and beautiful drifting in the water, like the afterimage of a candle flame.

The soul seemed to be about two inches long, although where it really ended and began wasn’t clear. It moved like fire, flickering with warm light. It darted around, making ripples in the water, and when it bumped or brushed against the walls of its glass prison, it made a melodic clinking sound, like a ring dropped into an empty wineglass. She looked more closely, nearly pressing her nose to the bottle, and in the soul’s wavering form she discerned human features, warped and quickly shifting — there was a wizened mouth, and there, two clouded eyes.

“Hello?” she whispered. “Can you speak?”

She held the bottle up to her ear and listened.

“Who are you?” said a voice, thin as a fraying thread.

“I’m Hinda. What’s your name?”

“Please, don’t make me remember,” said the soul. “I don’t think I can. Nearly ten months, I’ve been burning in Gehenna.”

“Then your sentence there must almost be over,” said Hinda, recalling stories her grandmother had told. “No one spends more than a year in Gehenna. Not even the most wicked of sinners. You must have done something really awful to be tortured for ten months.”

“Please.” The soul made a choked, sobbing sound. “I can’t stand another day in Gehenna. You saved me. Don’t send me back.”

“I don’t understand,” said Hinda. “Isn’t it better to serve the rest of your term quickly, so you can enter the World to Come?”

“You don’t understand. Each day in Gehenna is like a lifetime of suffering on Earth. For every wrong you inflicted on the world, you feel that pain sevenfold. Every day I feel the gnawing hunger and tooth rot of every beggar I turned away, the pain and fear of the children I’ve beaten, the heartbreak of the woman I wronged. Every good deed a person was supposed to do, and didn’t, becomes a lead weight on their back. People in Gehenna walk stooped over, with their beards sweeping the ground. The pain purifies one’s soul in preparation for the World to Come, but it’s too much for a weak sinner like me. Keep me with you. Leave the cork in place. Otherwise, when the Gates of Day shut tonight I’ll be lifted from the water, pulled back to the world of punishment by the force of the closing gates. You must keep the cork in, and wipe a daub of your spittle around the rim to disguise me and protect me from those winds. If you do that, after the Sabbath ends, I won’t be drawn back to Gehenna.”

“All right,” Hinda stammered. “I’m going to take you now to meet my friend.”

“Please be careful. It makes me dizzy when you move the bottle too fast.”

Cradling the bottle as best she could, Hinda ran to Basya’s house. It was at the edge of town, by the apple orchard. The squat, whitewashed cottage was quiet in the Tammuz heat, everything slow and languid, and Basya’s sisters barely looked up when Hinda tapped on the bedroom window, three times hard and four times soft.

A few moments later, Basya came outside. Her eyes widened when she saw the bottle held tightly in Hinda’s fist. “What’s that?”

Hinda grabbed Basya’s hand and pulled her around the corner of the house, orange in the light of the setting sun. Some inarticulate sense of shame, mixed with the thrill of having a secret for Basya alone, kept her from revealing the bottle’s contents until they were under the apple trees, well out of sight of any prying sisters.

“Look inside,” said Hinda. “I found a soul for you. Can you see it? You don’t have to be shy,” she said to the soul, which was cowering at the bottom of the medicine bottle, as if trying to get as far away from Basya as possible.

Hinda delicately handed the bottle to Basya, who held it to her eye. The faint shimmer of the soul could have been mistaken for light caught in a spiderweb.

“It’s a demon,” said Basya. “If it is what you say, it’s bad.”

“Say hello to my friend,” Hinda urged the soul.

The soul slowly began to move. “Hello,” it whispered, in a crackling voice.

Basya shrieked. Before Hinda could snatch the bottle, Basya threw it against the trunk of an apple tree, as hard as she could. It shattered just as the sun disappeared and the three stars marking the Sabbath’s end pecked their way into the sky. The soul hung in the air for a moment, its light reflected in splinters of glass and droplets of water — then, with a sighing sound, it whirled away into the air, pulled back through the Gates of Day and over the world’s edge, where the fires of Gehenna burn white-hot under a black sun.

______

Hinda and Basya didn’t speak for a long time after that night. Basya told Hinda she saw her as an evil influence. Hinda felt she had done something very wrong, and became sick with guilt. For many Sabbaths, she didn’t sleep, fearful that the spirit would find its way back to her, and curse her for breaking her word to keep it safe. But after the year passed, and the spirit’s sentence in Gehenna had surely been served out, Hinda tried hard to put the whole affair out of her mind. She and Basya resumed speaking after a while, although a distance remained between them. Basya had already become better friends with other, older girls. For the most part, Hinda grew into a lonely adolescence, which she didn’t mind — at least not until the day she watched Basya marry.

Basya stood under the wedding canopy at eighteen, her black braids cascading over her white gown, cheeks blushing under downcast, play-bashful eyelashes. She was marrying Elkhone, a man of thirty-five who had been married once before; he had lost both his first wife and his child in a difficult birth. His undesirable status as a widower was tempered by the fact that he was the wealthiest man in town, with shares in a steam locomotive company. With his offer of financial support to expand Basya’s mother’s fruit stand into a dry goods store, it was generally considered to be a good match. Elkhone and Basya got along well, too. There had been talk about them long before the engagement — people pursed their lips to see him stop by the fruit seller’s almost every day, beard trimmed and moustache waxed in the modern fashion; and at how Basya would toss her hair and laugh at his teasing, offering him the firmest sweet plums and cherries. Some of the villagers had accused Basya of chasing his money and whispered about the tricks she’d used to turn his head. But even they now cooed to see her under the wedding canopy, the picture of a perfect bride.

Hinda didn’t like Elkhone. She didn’t like the airs he put on, how he sneered at beggars as he blustered through the town, how he leered at all the daughters, including her, a lanky sixteen-year-old. Watching from the far end of the women’s side, Hinda squinted, trying to see Basya’s eyes through her veil, shamefully searching for some shadow of unhappiness, or even resignation. But when Elkhone lifted the veil, Basya’s eyes brimmed with what could only be tears of joy. Hinda’s heart ached with bitterness as she heard the wineglass shatter under Elkhone’s boot.

The vise on Hinda’s chest tightened as the dancing began and she watched Basya twirl and laugh with her friends — her new friends, most already married themselves. Her face felt hot and she wondered if she was possessed. She couldn’t keep from being pulled into the circle with the other daughters who jostled to dance with the bride — a good luck dance in the hope that they, too, would soon stand under the canopy. The reedy wail of the wedding band flooded Hinda’s ears, and she tripped through the dance steps until she stumbled into the inner circle of the bride. She felt stiff as a corpse. Basya was glowing, graceful. Hinda stared at the purple flush of wine on her lips. After a moment, Basya extended her hand to Hinda. Slowly, as if through water, Hinda reached out. But when she touched Basya’s hand, a powerful, terrifying burst of heat shuddered through her. Hinda jerked her hand away. Basya looked confused and a little hurt, and Hinda wondered if she, too, had felt it. The trill of the clarinet was piercing, painful in her head, and now everyone was staring at her. Hinda pushed her way out of the circle and ran from the courtyard, gasping for breath and fighting tears. From the corner of her eye, she saw Zalman, a yeshiva student her age, turn away from the dance in the men’s section to stare at her. The lanterns behind him flickered like burning souls.

_____

It wasn’t too long after the wedding that Zalman and Hinda’s families made arrangements of their own, and the pair were engaged and then married within the year. Zalman’s reputation as a good student protected Hinda from the disgrace she had incurred through her behavior at Basya’s wedding, which eventually faded from the repertoire of even the most enthusiastic gossips. Zalman was a rationalist with a good head for the law, and none too demanding of his wife. They still hadn’t conceived, but as Zalman’s mother kept reminding Hinda, “It will happen, there’s plenty of time yet.” Hinda continued to work with her mother gathering mushrooms, and wandered the forest when time permitted. She was generally regarded as nonthreatening, if odd. The community’s opinion of Basya and Elkhone, however, quickly turned. Elkhone took his wife around to all the big cities, and every time they returned, she had more fox fur around her shoulders, more rings on her fingers, more silk dresses, cosmetics, and fine leather boots. Basya, it seemed, grew bored of her friends, bored of her enemies, and bored of her family, and she let everybody know it with cruel precision. She soon became pregnant, and although the women of the village fawned on her, they cursed her through their teeth for her haughtiness, her insults, her demands, and her outbursts. All the while, Elkhone hired the men of the village away from their wives, promising good wages to blast through the countryside and lay railroad track. They returned weeks, sometimes months later, missing fingers and hands, their wages not even enough to pay for doctors to treat their injuries. Sometimes they didn’t come back at all. Elkhone and Basya had no problem spending their ill-gotten profit, but when widows came knocking for a pension, Basya chased them off, shouting, “There’s no money to spare!”

And then, one night, Basya went missing. The next morning, two fishermen found her by the riverbank, her black hair unbound and tangled in marsh grass. When the news came that she was dead, all the rancor in people’s hearts of the past four years was washed away by tears, and overnight Basya was as beloved as she had been on her wedding day. Everyone wept for her little daughter, and wept to learn there had been another child on the way.

They wept, too, when proud Elkhone fell to the ground and wailed by the riverside. But Hinda’s eyes remained dry. She had been in the forest when they found Basya, and barely made it back to town that evening in time for the burial. She wanted to cry but felt raw and parched. That night she didn’t sleep, and she brushed off Zalman’s attempts to comfort her. What, she wondered, had led Basya to the river? Maybe she’d been sleepwalking, or running from a thief, or perhaps she’d misstepped on a slippery rock. Or maybe she’d been chased by a wolf, like the one Hinda’s uncle had killed, and had chosen a watery death over disembowelment.

For the next week, Hinda went around in a daze. She catalogued every tenderness she and Basya had shared as children, and imagined sharing that same tenderness with each other as grown women. Basya, hoisting her into an apple tree, then pulling her own skirt taut to catch the apples Hinda tossed down. Basya at midnight, answering Hinda’s knock at her window, three times hard and four times soft, the two of them climbing up the ivy lattice, crawling onto the roof of Basya’s home, talking for hours as the moon rose above them, turning their skin to silver. Seeing Basya watch her sisters get married one by one, the dowry money slowly drying up. Basya’s fingers carding through Hinda’s hair. On Tammuz nights when fireflies outnumbered stars, Basya’s green eyes flashing their light back to them.

___

As the weeks wore on, Hinda began to worry about the length of Basya’s sentence in Gehenna. In her last years, Basya had cheated workers, she had been prideful, she had left people who came for their wages freezing on her doorstep. Hinda inventoried these sins and tried to imagine a numerical value for each one. How many days would Basya suffer in Gehenna for every kopek she and her husband hadn’t earned honestly? Would she feel hunger and cold sevenfold, her body aching from toil she’d never known on earth?

Hinda came to lucidity on a Friday afternoon, staring at an empty glass bottle. She had been cleaning out the effects of her grandmother, now gone almost seven years. It was one of her medicine bottles, its thick glass frosted with age. Hinda held it up to catch the gentle orange light of the sunset that heralded the Sabbath’s arrival. The sunlight danced in the bottle. She surprised herself when she reached for the water jug to fill the bottle, and set it under the bed. A smile crept to her lips. She turned back toward her husband that night, but in the early hours of the morning, she woke up knowing that something was there. She looked under the bed, and saw a thread of light swirling in the bottle. She picked it up and went out into the night to talk privately.

The spirit in the bottle wasn’t Basya; it was the soul of a thief from far away. When Hinda gave him Basya’s name and description, he said he had never heard of her. “Don’t give up,” said the spirit. “If she lived in this town on earth, she probably visits often. Leave a lot of water out and you’ll catch her eventually.”

“No,” Hinda realized. “She hated it here. She won’t come back — unless, maybe, if she knows I’m seeking her. Please, when you go back, tell her — tell anyone, so they might tell her — Hinda is looking for Basya.”

“I will,” said the spirit, “But in return, keep me sealed in this bottle a little longer, until tomorrow night, and spare me from another day of torture.”

Hinda corked the bottle, then licked her thumb and brushed it around the bottle’s rim, as the soul had taught her to do all those years ago.

“Thank you,” said the spirit, “and I’ll repay your kindness further with a warning. The charm you work disguises the soul, and frees it from the force that pulls it back to Gehenna, but only for a time. The punishing angels cannot be outsmarted or defied forever. They assemble and count the sinners on the next Friday before the Sabbath begins, and if they find one missing, they will scour the earth like bloodhounds, track it down, and drive it back to Gehenna with fiery whips. If you do find your Basya, remember this, and let her go when you must, for I do not know what punishment the angels might ordain for a living accomplice.”

Hinda spent the rest of the Sabbath in contemplation, and went about her chores on Sunday with quiet satisfaction, the bottled spirit a pleasant weight in her pocket.

____

Before the next Sabbath, Hinda brought home thirty empty medicine bottles from the trash heap in the woods. When Zalman left for evening prayers, she cleaned them, filled them with water, and lined them up beneath the bed. In the middle of the night, she awoke. It was pitch black outside, and at first she didn’t understand why the room was washed in light; she thought her Sabbath candles might still be burning. She looked down and realized the bed was illuminated from below, casting her and Zalman in sharp relief atop it — and she heard a gentle, glassy sound, like windchimes. A laugh of joy bubbled up from her, which she quickly muffled for fear of waking her husband. She lay down on the floor beside the bed, watching the yellow light of the souls pool on her hands and nightdress. She carefully corked the bottles and brought them to the cellar, where their glow would be unnoticed.

She interviewed each soul and learned that none of them had seen Basya. Again, she cut a deal to keep them, this time a few days further into the week, in return for spreading the word among the sinners of Gehenna. On Sunday, Hinda borrowed some money from a cousin, and enclosed it with a letter to an apothecary wholesaler in the nearest city, saying she planned to go into the business and would need two hundred medicine bottles to start. They were delivered by a bemused wagon driver on Thursday morning, and Hinda didn’t mind her neighbors’ stares as she heaved crates of bottles into the cellar, and then ran to and from the pump with her biggest pail to fill them. She stayed in the cellar that night instead of going to bed with her husband, and the shelves swam with light and sang with hundreds of chiming voices. Again, none were Basya, although one said he had seen a sinner like Hinda described, with black hair and red cheeks, in the place where exploiters were punished. He wasn’t sure if he could find her again. By the time Hinda had finished talking to each of the souls, it was almost Sabbath’s end, and she had spent all day in the cellar.

So several Sabbaths passed.

“I don’t know what to do, Hinda,” Zalman said after about two months. “I don’t know what to tell people anymore.”

They were standing in front of the empty hearth, and when he spoke, Hinda didn’t look up. By now, her bottle collection had doubled, and most of her time was consumed with preparing bottles for the Sabbath influx of souls. She liked to think of herself as an innkeeper for the sinful dead in need of rest. She’d even been getting to know her regulars. Per the advice of the thief’s soul, she made sure all the bottles were uncorked by Friday morning, with no hangers-on, despite the spirits’ wheedling and begging. With every passing week, she felt her chance of finding Basya slipping away. Any day could be the end of Basya’s sentence in Gehenna; before long, she’d vanish into the World to Come, and Hinda would die without ever seeing her again.

“ — don’t you remember what your uncle said, about the wolf?” Zalman was saying.

“Yes, of course,” Hinda said, distractedly. It had become clear to her some weeks ago, after he had barged into the cellar unannounced, that Zalman, the rationalist, couldn’t perceive the souls at all.

“Your uncle didn’t kill a wolf.” Zalman waited until Hinda met his eyes. “You never stopped to think about it, did you? That scar was from an axe blade that flew off its handle and into his leg. Just think about the shape of it. But no one ever told you to stop believing, because they all thought you’d figure it out on your own, like a normal child. You’ve always lived in stories.” He took her by the hand. “This has to stop, Hinda. It’s humiliating. You need to make this stop, or I will. Wake up to the world you live in.”

A world where axes bury themselves in legs, and railroad lords work men to death, and young mothers drown and you never get to know why? A story can make an axe bite like a wolf. The right story can bring back the dead, give speech to souls, burn you up on the inside.

Then she said, “I’ve been having pregnancy dreams.”

Zalman’s eyebrows shot up, and she could tell even the most empirical parts of his brain were reeling, because scholars as well as women know a dream like that is a sign something is happening in the dreamer’s body. “Tell me everything.”

Hinda smiled, pleased that now he was really listening to her. “In my dream, I watch the horizon. As the light turns, my body fills with warmth and I feel another sweet little soul sharing my body. It’s a strange sensation, but good.”

Zalman, too overcome to speak, took her hands. He’d been praying for a son, who would say the mourner’s prayer for him after he left this world. Hinda kissed his forehead and instructed him to go to the study house and learn Talmud in her name, recite psalms with the other men, and pray that the omen in her dream would be fulfilled. That is how she got rid of him.

_____

It happened five months after Basya drowned. Hinda had just lit her Sabbath candles and gone down to the cellar when she felt the presence behind her, hot, almost like a living breath. She knew without turning around, but she turned anyway. Basya’s soul flickered in a bottle by the stairs. “Hinda,” she whispered. “You’ve been searching for me.”

Hinda felt just as she had at Basya’s wedding, tongue-tied and dumb, pulled into a dance she didn’t know, while Basya whirled and glowed before her. She stumbled forward, knocking over a few bottles. She knelt down in front of Basya, placing one hand on the medicine bottle and feeling it pulse with gentle warmth. In the yellow light, Hinda could make out her proud features, just the way they had looked in life.

“I knew you wanted to find me,” said Basya, “but I was afraid. I was afraid to come back to this town and hear what they say about me now. It would have hurt too much to see my daughter. And you — I thought you might be angry with me. Are you angry with me?”

Hinda’s throat felt thick. Her mouth started to form the word “No,” but it felt wrong. Basya was the only person who had ever known her, who had seen her for who she was. And then she’d pulled away and kept her out, as she kept everyone out. Yes, there was anger smelted in with all the shock and relief and and love that leadened her tongue. She had always felt smaller than Basya, more fragile, less real.

Her knuckles were white around the bottle. How easy it would be to smash it — as Basya had done, years ago — and cast her soul to the mercy of the winds.

“Sweet Hinda,” Basya said. “It’s all right to be angry.”

“You left me,” said Hinda, finally, really crying now. “You left!”

“I never wanted to hurt you,” said Basya. “I am so sorry. Look at me, Hinda. This life was never enough for me. It made me bitter and mean, and there were parts of me that delighted in being resented. I always felt so angry, so lonely, even when I was surrounded by people. But you were always at peace just to be alone. You were the only part of my life that didn’t spoil, Hinda. Oh, I wish I could hold you now!”

“I don’t want to be alone anymore,” whispered Hinda. Bottles around them were filling up with spirits, casting light throughout the room. None shone brighter than Basya. “And I don’t want to leave you again,” said Basya. “I’m here now. Stopper the bottle and take me outside, won’t you? I haven’t seen the stars in a very long time.”

That week, Hinda took Basya into the forest every day, and the late summer nights were sweet enough for her to spend outside, although she hated every minute that sleep stole her from Basya. When Hinda was awake, the pair talked until her voice rasped. Basya wouldn’t discuss her suffering in Gehenna — it was hers to bear, she said, and she wouldn’t burden Hinda with it — she wanted the time they spent together to be spared all the suffering of their time apart. She asked about her daughter, and Hinda told her how the girl was growing up with all her mother’s cleverness. Hinda described the spring and early summer, how the cherry trees had blossomed and moss had crept across the forest floor. Basya told her about the bitterness that had brought her to the river’s edge, how all her years of striving for the life she thought she wanted had laid her low. Hinda talked about the wedding, too, that terrifying heat that had filled her body, which she couldn’t explain, even now.

With every passing hour, she felt Friday closing in. When the wind came from the west, she could almost smell the brimstone of the punishing angels, scouring the earth for Basya.

But with every passing hour, she felt Friday closing in. When the wind came from the west, she could almost smell the brimstone of the punishing angels, scouring the earth for Basya. On Thursday evening, as she watched the sunset give way to darkness, she could hardly breathe. She felt Basya’s fear, the slight edge to her laughter, the desperation in the questions with which she peppered Hinda. Hinda cursed the fact that Basya had no body to press against for comfort. As stars began to purl the sky, Basya whispered, “Please don’t let them take me.”

“I won’t,” said Hinda.

She couldn’t hold back sleep then, and curled up on the mossy ground, the bottle pressed to her chest, Basya fluttering inside like a second heartbeat.

______

A light streaming through the trees in the predawn silence was so bright that when Hinda hazily awoke, her first thought was that she’d missed sunrise. Her second thought was that it was coming not from the east, but from her house. Fire. She sprang up and sprinted, jostling Basya in the bottle, realizing halfway home that she wasn’t wearing any shoes. She burst through the trees and wondered why she didn’t smell smoke — until she saw that the light was coming from hundreds of souls flying from her cellar, streaking into the sky. She crept toward the cellar door and looked inside. She saw Zalman, gentle Zalman, frenzied, attacking the last of the soul bottles, sweeping them off their shelves and smashing them under his boot heels. As the final soul sighed out of the cellar and into the sky, Zalman looked up and saw her. His eyes were rimmed with red. Before he could speak, Hinda turned and ran back toward the woods. She ran, not caring where her feet were taking her, until Basya cried, “Stop.”

Hinda had come to the river. She steadied herself on the rocks. Her hand was sweaty around the bottle. She turned to look behind her. The sun was up, but from the west, a faint red glow.

“The angels,” Hinda murmured.

“We can’t outrun them,” said Basya.

“Break my bottle on the rocks and run. I’ll find you in the World to Come.”

“No.” Hinda felt the force in her voice, from some part of her that had never spoken before. “I want to be with you, now.”

She brushed her thumb around the bottle’s lip, and felt that stirring of heat and power, and what she now recognized as the insistent pull of fate.

“Basya,” she said, “would you like to share my body? Come into me and hide yourself, and stay with me as long as I remain alive?”

“Yes. Yes!” said Basya. “Share yourself with me, let me see through your eyes, touch with your hands, laugh with your voice. Quickly now!”

The horizon was a line of fire. Hinda unstoppered the bottle and pressed it to her lips. She tilted her head back and swallowed Basya’s soul. A warmth coursed through her, which turned to a burning heat — but it didn’t hurt, and she wasn’t afraid; it was cleansing, transforming. She realized she was laughing — both of them were laughing, two voices weaving together …

The angels blazed a red path through the sky, and paid no mind to the creature by the river’s edge, a double-souled creature. One soul so perfectly merged with the other that any watcher from outside their body wouldn’t be able to tell they had once been two. The creature rose, a little unsteadily, and looked around. Satisfied that they were not pursued, they walked away from the setting sun, into the quiet Sabbath night.

Weaver is a playwright and translator, and the Rona Moscow Senior Fellow at the Yiddish Book Center.