This month celebrates the eightieth anniversary of Superman’s first appearance in Action Comics #1. What was meant to be ephemeral and cheap entertainment for a nation starved of dreams soon became one of the greatest popular cultural behemoths in history. But justice and the American way never truly caught up for Superman’s creators — two Jewish boys from Cleveland named Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Although the legacy of their creation endures stronger than ever, Jerry and Joe were forced into penury, lawsuits, and near-obscurity.

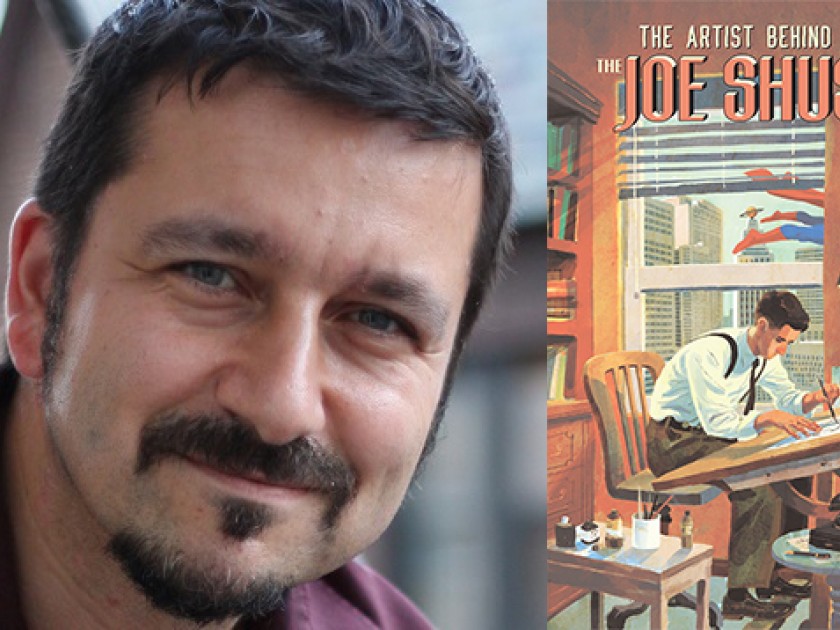

While the story of Superman is well-known throughout the world, the true story of his creators and their plights hasn’t received as much popular scrutiny. A forthcoming comic focusing on the life and travails of Shuster aims to remedy this imbalance. The Joe Shuster Story: The Artist Behind Superman, written by Julian Voloj (Ghetto Brother) with art by Thomas Campi (Magritte: This Is Not a Biography), is not only an authoritative account of Shuster’s life growing up as a poor kid in Cleveland, but also a riveting play-by-play of the early years of American comic books.

AJ Frost chatted with the author and illustrator before the book’s release. In this installment, author Julian Voloj shares some thoughts about writing and collaborating on the book with illustrator Thomas Campi.

___

AJ Frost: Hi, Julian. I’ve been anticipating this book since it was first announced a while ago. Where did the idea to tell the story of Joe Shuster originate?

Julian Voloj: I feel like there are many people who vaguely know about Joe Shuster, but don’t know the whole story. A graphic novel is the perfect medium to tell that story in an entertaining way that can reach a lot of people. I come from a journalistic and academic background. Three years ago, I released Ghetto Brother —my first graphic novel — but before that I had written close to twenty books on academic topics. I knew the comic book history, but I delved into it much more after reading Gerard Jones’s books, like Men of Tomorrow; I really tried to study as much of the story as I could.

I’ve been waiting for someone to do such a book, because it’s a great story. I couldn’t believe that nobody came up with the idea to tell it as a comic book. If you’re a fan of comics, at least in the United States, you probably know the story, but most comic book fans abroad are probably not aware of it. [Ed. note: The book is being released in around ten countries this year.) But, you know, while Americans are aware of the story, they’re not necessarily going to read a 300-page academic book on the subject. A graphic novel makes the story of Shuster so much more accessible.

AJF: What was the research like when you were starting this book? You were always interested in the “real-life” story. Was there ever a point when you thought your book would be more like a fictionalized retelling à la Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay?

JV: It’s not that I’m specifically writing nonfiction graphic novels. My interest is nonfiction stories. I come from an academic background and from journalism…that’s what I’m trained in. I really wanted to tell this story, and I was concerned about really documenting every scene; every scene in the book is based on something that I’ve found, be it in academic books, legal documents, or interviews. Everything is based on something. Now, that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s all true, because people have different versions of memories, and this version is written from the perspective — or the imagined perspective — of Joe Shuster. But it was pretty clear that it should be a nonfiction book, which, in theory, has a smaller market, but I think that if it’s well done, readers will appreciate it.

AJF: It was interesting, while reading the book, to see so many prominent figures from comics history featured, including people who are still alive. For example, you feature the legendary comics figure Neil Adams later in the book, as well as the more insider‑y Jay Emmett, who passed away a few years ago, unfortunately. What was it like hearing those first-hand stories?

JV: In a way, it was a little too late, because a lot of the key people had already passed, so it was pretty much just reading interviews with them. But also it was perfect timing because, thanks to the internet, there are now so many resources available: interviews, videos, Superman audio, the radio show, and all 17 episodes of the [1941 – 43 Fleischer Studios Superman] cartoons. So you actually could access a lot of the stuff for free, which was amazing.

One cool thing, for example: Jerry Siegel was invited on a radio show, and you can hear his voice; he had such a squeaky, boyish voice, but he was already successful, and this was at the height of his popularity. I wouldn’t have had access to these amazing resources ten years ago. So even though all of these people passed a long time ago, you actually have a lot of these things you can pull from, which is great.

AJF: What was it about Joe Shuster’s story that really resonated with you? Did your perception of him change while you were researching and writing the book?

JV: In 2013, my wife and I were in Detroit with our two kids and my in-laws offered to babysit while we were there. We decided to go for a weekend getaway from Detroit (without the kids). And we went to Cleveland, because it’s around the corner, and I was interested in the Superman story. I’m also a photographer, so I’ve always been interested in these former Jewish neighborhoods. Glenville, which is where Siegel and Schuster met for the first time, is the same kind of place. The majority of the people there were Jewish, and now it’s predominantly an African-American neighborhood. So one morning, I decided to explore Glenville. I saw some former synagogues, and the place where Siegel’s house still stands, and the place where the Shuster residence once stood. I thought I would be more inspired by it, but it’s just a rundown neighborhood, which is unfortunate, because I think it could be such a tourist attraction. I love neighborhoods like this, and I’m always curious, so I spoke with some locals, who I think were surprised that I was white, but also surprised that I decided to park my car and just walk from the old Shuster residence to the Siegel residence. It’s less than a mile. I just wanted to experience the walk that they took every time they went to see each other. Around the same time, I spoke with my agent about how I really wanted to do a graphic novel on this. Half a year later, Columbia University got a donation of letters written by Joe Shuster. They gave me access to this box of letters even before it was cataloged, which was amazing. It was just sitting there, not even in Columbia’s system yet.

These letters…they were heartbreaking. There was stuff about the time Shuster had medical bills he couldn’t pay, his mom was dying; he even writes about Superman generating $50 million and not getting one cent of it. He writes letters to friends — I think all of them were Jewish — and he writes about when he had money that he was donating to Jewish charities. Really, it was just heartbreaking. And reading it in his voice, too. I mean, you think about how at the same time, people were making millions from Superman even before the movie came out, and meanwhile this guy can’t even pay his medical bills. And so, for me, it was clear that I wanted to write from his perspective, because in the duo of Siegel and Shuster, Siegel was definitely the spokesperson. He was the one negotiating the deals, he was the one going on talk shows, he was the one pushing for the trials and the legal claims. He was the dominant one in this relationship. I think Joe Shuster was more of a tragic figure. He also has a bit more of the unknown factor. I feel like often with illustrators, especially with graphic novels, they’re doing the majority of the work but they’re often in the background. Even for this book, it took me a few years to write the text, but it also took Thomas Campi a few years to illustrate it.

Reading those letters, I felt that there were things people actually got wrong. In one of the boxes of Shuster’s letters, there was a copy of the playbill from the Superman Broadway show [It’s a Bird…It’s a Plane…It’s Superman which debuted in 1966], and everybody wrote that he was too poor to go see it in the theater, but I found that he actually was invited to the party and met the actors. And this was at the time when they were trying to come to terms with DC Comics. He even writes that they treated him well, and nobody knew about this because it just came out of this box.

There were just these little things that most of us got wrong because there were no interviews with Joe Shuster — he was more of a shy guy. And so, in a way, I give him a voice with this book. And where it’s possible, I’m using some interviews, and it’s really the way he would speak. In a way, I feel like it’s elevating a marginalized voice who’s not known as much as Jerry Siegel. There are just more interviews with Jerry Siegel. Even when they had interviews together, Jerry was the one talking.

AJF: How was the aesthetic sense of the book informed by your writing, and how much of it was Thomas taking what you wrote and just going with it?

JV: When I was writing it, and pitching it to my editor, he sent me a lot of portfolios. And there were really a whole range of possibilities. Some looked very American, even like a superhero comic, and I felt like I didn’t want it to be like that. My agent met Thomas in China, which is crazy because he’s Italian, and told me he met this guy and thought I’d like what he’s doing. The moment I saw his portfolio I knew he was it. It was this Americana feel to it; it really was a perfect fit. I was joking with Thomas, because we both love the show Mad Men, so we were saying that this is the Mad Men of comics. Some of the aesthetics are really like Mad Men, so I feel like the style perfectly fits.

We did things like Skype, and Dropbox, and we transferred things over the internet. It’s a lot of stuff he got from me to work with online. The funny thing is that while he was working on it, he was moving from China to Australia, so the time difference was a challenge too. If we had done this book ten or fifteen years ago, we probably wouldn’t have found each other. The fact that I can work with an Italian artist in Australia worked perfectly. I think it’s really like a fine art book. It’s definitely strongly his style, but it also fits perfectly with my vision.

AJF: How and why does the sub-genre of biographical comics speak to you as a reader, writer, and academic?

JV: I write frequently for a Swiss Jewish magazine, so I’m interested in Jewish culture stories and Jewish contribution to culture. I find stories that fascinate me, real stories, and tell them in a journalistic form. So the fascination with real life stories and Jewish history definitely was part of it. And I feel like there is a growing demand for it. I feel like telling the real story is my way to honor the pioneers. The first generation of comic book artists are stories of a lot of broken hearts, people who were screwed over by publishers. Telling stories like this is important, to honor those people who can’t tell their stories anymore. Even if it’s just a story about the Superman creators, I put it in the wider context of the comic book industry. That’s why a lot of people are also honored in it, and have guest appearances, and can sort of tell their own stories. It’s history.

AJF: You said it’s Jewish history?

JV: It is. The comic book industry was 90 percent Jewish. And even the trials in the ’50s [The Kefauver committee hearings, which linked comic book reading to juvenile delinquency] had some anti-Semitic undertones. So, yeah, it’s a fascinating piece of Americana, but also of Jewish history.

AJF: Okay, last question: What does the story of Superman and Joe Shuster mean to you as a lover and writer of comics?

JV: Superman is really just a part of American folklore now, and in a way, the Siegel and Shuster story and the bad deal they made is almost like the original sin, in a way, of the comic book industry. So, I think it should be told not to forget where it comes from. Hopefully with my book, the original sin of the comic book industry will be more known, and the creators more appreciated. I feel like it’s something that is contemporary. A lot of people think that the comic book industry is just these two big companies, but of course there are many people who want to do their own thing, and there’s a growing market for independent artists. Hopefully people will appreciate the independent artists and give them a chance when they go to a convention and see things that are not like the characters that you see everywhere, but artists trying to figure out things that are not in the mainstream.