This month marks the eightieth anniversary of Superman’s first appearance in Action Comics #1. What was meant to be ephemeral and cheap entertainment for a nation starved of dreams soon became one of the greatest popular cultural behemoths in history. But justice and the American way never truly caught up for Superman’s creators, two Jewish boys from Cleveland named Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Although the legacy of their creation endures stronger than ever, Jerry and Joe themselves were forced into penury, lawsuits, and near-obscurity.

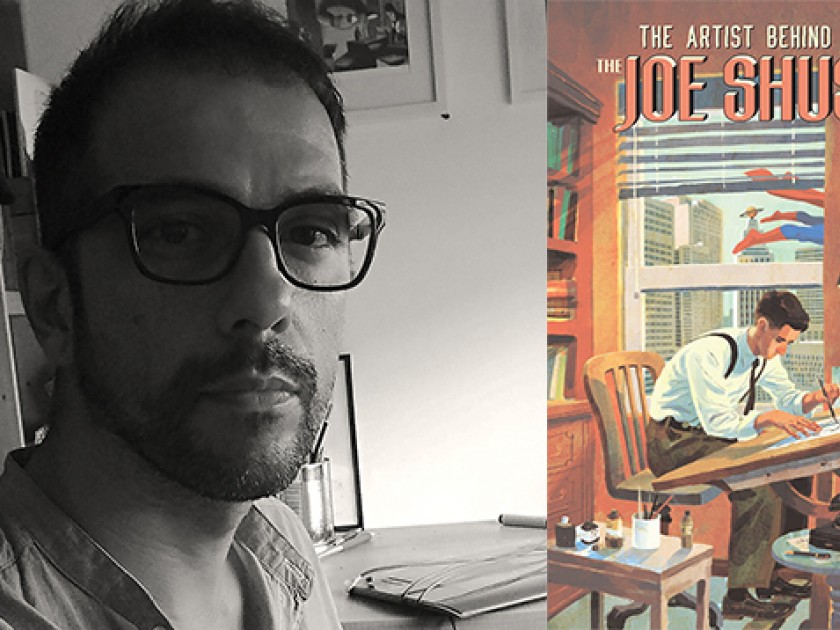

While the story of Superman is well-known throughout the world, the true story of his creators and their plights hasn’t received as much popular scrutiny. A forthcoming comic focusing on the life and travails of Shuster aims to remedy this imbalance. The Joe Shuster Story: The Artist Behind Superman, written by Julian Voloj (Ghetto Brother) with art by Thomas Campi (Magritte: This Is Not a Biography), is not only an authoritative account of Shuster’s life growing up as a poor kid in Cleveland, but also a riveting play-by-play of the early years of American comic books.

AJ Frost chatted with the author and illustrator before the book’s release. In this installment, illustrator Thomas Campi discusses his early influences, the challenges of working on a book while moving continents (a Superman-ish feat!), and the legacy that Joe Shuster left for artists today.

Click here to read AJ’s interview with author Julian Voloj.

AJ Frost: Thomas, thanks for taking the time to chat. I wanted to start with your background for a moment. Superheroes are such an ingrained part of the American psyche, but they might not translate as well elsewhere. Growing up in Italy, what was your attitude towards superhero comics, or comics in general? What was the cultural attitude towards them?

Thomas Campi: I started reading comics when I was fourteen years old. A friend lent me Dylan Dog, a black-and-white series that came out monthly. Dylan Dog was horror, but it had so many different genres in it as well: philosophy, humor, love — it was just brilliant. I didn’t really read superhero comics even though I knew about them; my interest was limited to Dylan Dog at the beginning. My attitude was simply that of a kid being amazed by drawings and words that made my mind dream, and let me live adventures by sitting down in silence in my room or in a park. In Italy at the time — it was the ’90s — like in the US, comics were popular but seen as something childish, not really recognized as a form of art. But even this … it was a concept I understood and realized years later.

AJF: When did you first come across Superman and the work of Joe Shuster? Superman is so symbolic of American aspiration that I’m curious as to how he’s perceived in a non-American context.

TC: The first memory I have about Superman is from when I was probably five or six. I went to a newsagent with my dad and I wanted him to buy me something (no memory of what). Among all the children’s magazines, there were a few superhero comics. My dad pointed at Superman and said: “That’s Superman.” (But you know what he was called when I was a kid in Italy? “Nembo Kid.”) But at the time, I was more into cartoons like Scooby Doo or The Flintstones. It wasn’t until I watched the first Superman movie with Christopher Reeve that I actually got to know and understand Superman. Joe Shuster’s artwork was a late discovery.

AJF: The Italian comic tradition is very different from the American one. Would it be fair to say that the work of Romano Scarpa or Luciano Bottaro, or any of the major Disney artists, is more well-known than, say, the work of anything from the Big 2?

TC: Actually, I wouldn’t say that. American comics are popular in Italy as well. We do have our own Big 2: Disney and Sergio Bonelli Editore. When I got into comics — as a reader and a fan — I met a lot of people with different interests: those devoted to Disney, the superhero fans, the manga fans, and so on. With that said, Scarpa, Bottaro, and Giorgio Cavazzano are masters for anyone who understands something about comics.

AJF: As an artist, what was your first sense of Shuster’s work? Was there something to it that seemed special, or did it seem more like a relic of an earlier time of illustration?

TC: A little bit of both. I thought it was special because Shuster was just a kid when he did the first drawings. And it was in the ’30s, so I pictured him in those times: the cars, the suits with large pants, suspenders, wooden nib pens, big pieces of paper; it’s all fascinating. He made history. The artwork can seem naïve if seen through the eyes of somebody working digitally or simply used to modern aesthetics. I myself think it’s great if you put it in context. I’ve studied and reproduced a few of his drawings for the book. The inking, and even the way he simplified anatomy, were pretty impressive for someone of his age who didn’t have the amount of comics and references we have nowadays. Personally, I’m a big fan of those old-school styles.

AJF: Let’s talk about The Joe Shuster Story for a moment. What was the process of collaborating with Julian like? When I chatted with him, he mentioned that you were moving from China to Australia while working on the book. How much of a challenge was it to keep up with all that at the same time?

TC: It was challenging. When I was approached by our agent about the Joe Shuster story, I was living in Hangzhou, China. But I said yes right away. At the time, I had just received my talent visa and I was about to move to Sydney. Another challenge was that I was still working on Macaroni! for my French publisher. And one more thing — and it’s something people don’t talk about too much — is that as an illustrator or author, you get paid with advances and then royalties, but the advances aren’t enough to pay bills, so I had to squeeze in Magritte: This Is Not A Biography for a few months to cover the expenses. It’s the life of a freelancer, and I love it!

I also felt some pressure at the beginning. Working on such a popular story about the two artists who created the first superhero and basically helped the birth of the American comics industry was intimidating. But the more I got to know about Joe and Jerry and their genuine passion for telling stories and for comics, the more I felt close to them and confident (if that’s possible when making comics) in approaching the 160 pages I had to storyboard and draw. Julian’s narration is full of emotion and based on solid research. It’s also written with no specifications of panels and page numbers. He trusted my storytelling skills, which brought an inspiring freedom to my creativity and the approach I took in telling the story.

I began reading and annotating the script during nights and weekends since, at the time I received it, I was still working on another book. I broke down Julian’s script into panels and wrote descriptions of how I imagined each particular scene. Regarding the artwork, I didn’t want to define everything with a line, not even in the first steps of the creation of the page. That’s why, after I sketched the storyboards, I simply painted over them without penciling, trying to give a more painterly feeling to the final page — something that could suggest a particular mood, describe a moment without using too many details that would have filled the page but not added any emotion. Basically, both Julian’s and my main concern was the story.

AJF: What was it like recreating Depression-era America from your vantage point as an expat in Australia? That must have been its own unique challenge. Did you do any independent research?

TC: The beauty of comics is that you can do whatever you want by yourself in your studio. You don’t need the budget you would for a movie or a big team of people. I’ve done several books set in France and Belgium while living in China and Australia. I think the most important thing is to be honest and passionate about the story you’re telling. In comics, in my opinion, there’s no need to represent everything in detail, or to be incredibly realistic in anatomy, perspective, background, or lighting. I think the most important thing is to give an “impression,” like Impressionists did in their paintings.

During my life, I’ve watched many old American movies, read American novels and comics. But when you’re creating something, you can’t just trust that kind of knowledge — it can only be the starting point. I did my own research about Joe Shuster, Jerry Siegel, and Depression-era America. I gathered photos of every kind, watched videos from those times, and then I tried to recreate, with my own filter, an impression of that era — which I guess was from a European point of view, even though I’d like to think of it as just a personal, creative one.

AJ F: What do you think the legacy of Shuster is — not just for comics creators or comics readers, but for artists and dreamers? And what did you personally walk away with — emotionally, artistically, or personally — after working on this comic?

TC: What Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel did (in part) is the dream of every artist: creating something that will make you live forever, a legacy. But what actually impressed me was their tenacity, perseverance, and, most of all, their passion. They had fire inside, that fire that makes you sit down in your studio for months — alone in most cases — trying to create something that you can be proud of and that people will enjoy and hopefully remember. I believe that any kind of artist — whether a comic book artist, musician, filmmaker — should have that kind of fire. It’s what makes you an artist, the compulsive need to create. I believe that is Joe Shuster’s legacy.