A synagogue in Safed, image courtesy of the author

1.

I am a visual learner. Images make the greatest impact on me. Sometimes they remain in my subconscious for decades, then float to the surface like black-and-white photographs emerging from a bath of psychic alchemy.

2.

First: the nickel-plated bracelet on my wrist. I’m thirteen years old in 1972 and the United States is nearing the end of its twenty-year war in Vietnam. A boy’s name and military rank are engraved on the bracelet, a soldier MIA. The boy is a stranger. The bracelet is heavy. I won’t know for a while yet the meaning of this weight, this signifier of war.

That same year: my formal Hebrew school education ends. Still, I’ll carry into adulthood a palimpsest as haunting as the melodies of prayers, many of which I can now read only in transliteration, my finger tracing the letters like braille.

3.

It’s 1984, and Sarajevo hosts the Winter Olympics: East German skater Katarina Witt glides, twirls, and leaps across the ice in the Zetra Olympic Hall. A glittering tiara never threatens to topple from her head. She smiles triumphantly, clutching those two gold medals to her heart.

4.

It’s 1992, and a war has begun in the former republics of Yugoslavia. In the streets of Sarajevo, bodies are stacked like cord wood. In an aerial shot, children and old women run from snipers’ bullets. They scatter like frightened rats.

These images meld with those of the Holocaust I’ve seen in Hebrew school: bodies piled in gaping pits. Skeletal figures packed tight in squalid bunks.

5.

In 2002, I begin research on a novel about the war in Bosnia. I won’t settle on its title—Nermina’s Chance—for another thirteen years.

6.

In 1992, Zrinka Bralo is a Bosnian TV journalist in Sarajevo. Along with her colleagues, she is trapped inside the TV1/CNN studios at the outset of the longest siege of a capital city since World War II. Snipers will terrorize Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) and Croatian civilians for nearly four years, but in 1993 Bralo escapes in a convoy that winds its way through dark mountain roads, with no headlights to guide the drivers. Their route leads to a UN tunnel beneath the Sarajevo airport. I will later describe in my novel each detail that she shares. Zrinka’s experiences will become Nermina’s. My protagonist will feature Zrinka’s greenish-blue eyes, her angular cheek bones, the anguish of a survivor, and the singular will to move beyond the prison of memory.

7.

It’s 2003. My computer screen freezes as I Skype with a woman in a chunky sweater and jeans, chin-length brown hair, and eyes that hold me with their sincerity and urgency. I’m conducting an interview with Zrinka Bralo, now an activist for refugees. From her London flat, she answers my questions.

8.

In 2009, our daughter is studying at Hebrew University for her junior year abroad, and my husband and I make our first trip to Israel. At Yad Vashem, I gaze up to the ceiling where a narrow seam of light guides me beyond my fear.

9.

It’s 2012, the start of my MFA program, and I am fifty-four years old. I’m writing a novel that begins in 1992 Bosnia, when the Bosnian Serb forces of the VRS deploy a campaign of systematic rape and genocide that will ultimately extinguish the lives of 100,000 people — Bosniaks and Croats. The true number of women who are raped will never be known, but estimates range from 10,000 to 60,000.[1] These horrors will haunt countless others — survivors and their descendants — forever.

10.

In 2017, foreign affairs analyst Nadina Ronc is being interviewed by another TV journalist for a segment on TRT World. Composed and articulate in a crisp red blazer, Ronc tells the story of her aunt and uncle — imprisoned and tortured in the Luka concentration camp in Brčko in 1992. Her uncle was killed. Her aunt was raped repeatedly. She recounts these atrocities — two among multitudes — and notes that her aunt’s torturer served only two thirds of his prison sentence.

“My aunt died in Germany. She never told others what happened because she was afraid someone would come and get her. After the rape, she had two strokes and some years later she died.”

11.

In January 2021, my Covid-shrouded worldview is bleak. These are the images I still remember from Yad Vashem: a metal bracelet with a five-digit prisoner number engraved into it. A black-and-white photo of US military planes flying over Dachau; the caption states that their superiors had ignored the pilots’ intelligence identifying the site as a concentration camp. And, vaguely, an exhibit that consists of a cylindrical cavern of darkness. I gaze down into this void from an observation area. Images of children’s faces float in the dark. Flickers of light depict more than one million children who perished during the Holocaust.

12.

In May of 2021, Zrinka Bralo’s hair is gray, short, and stylish. This accentuates her vibrant expression on the web page of Migrants Organise, the London-based NGO she leads. As promised, she’s returned my manuscript and the foreword for Nermina’s Chance.

13.

July 2021: I interview a young Bosnian woman who remains anonymous because her family forbids discussion of the war.

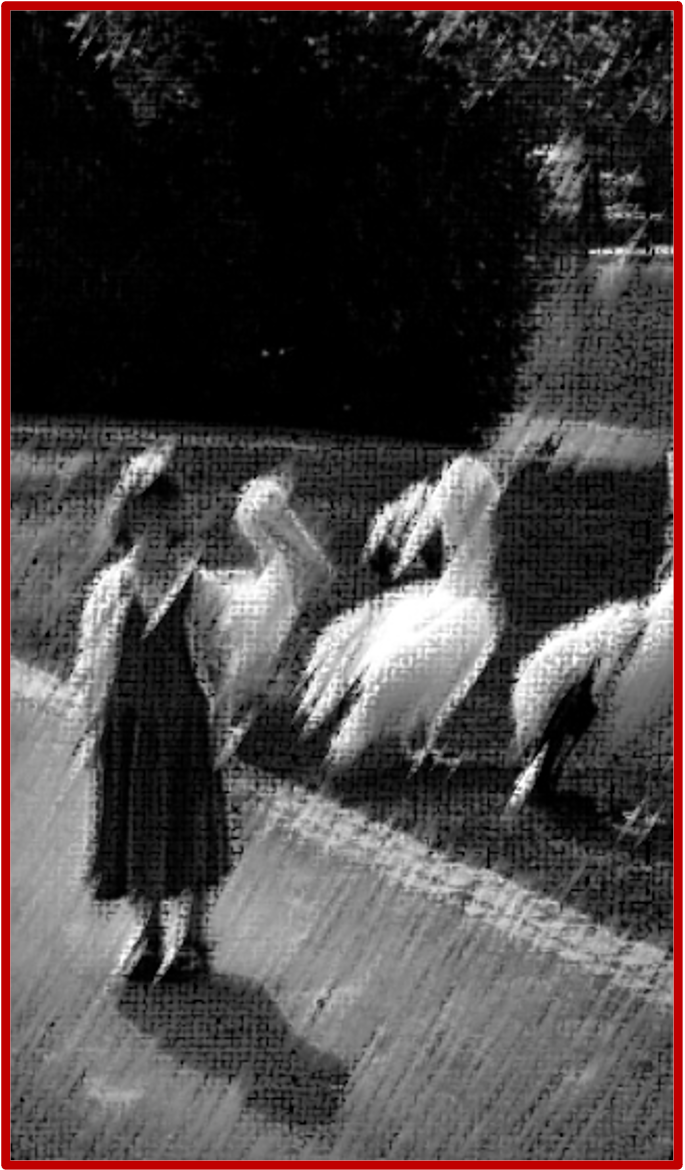

A photograph of Anonymous, courtesy of the author

“I was born in Prijedor in 1991 … one of the cities that suffered the most. If you were a Muslim, you were either taken to a concentration camp (and raped, tortured, and killed there) or they would simply kill you in your own garden.”

A photo of anonymous shows her as a five-year-old girl standing in front of a gaggle of pelicans at a zoo in Germany. Bangs frame the child’s wide, brown eyes. She wears a denim jumper, mauve tights, and Mary Janes. Her expression is neutral, no hint of a smile. In the altered, black-and-white image that I post, this detail is disguised along with the others.

14.

August 2021: On my computer screen, Nadina Ronc sits in her London flat. Instead of a red blazer, she wears a camel-colored turtle-neck sweater. After many emails, I’m “meeting” the striking, intelligent woman from the 2017 TV interview. She tells me about her family’s exodus from Bosnia to Germany, and then to the UK. I listen again as she recounts her aunt’s story.

15.

On screen in October 2021, just days before my novel will be released, my new friend smiles. Her glossy, brown hair brushes her collar bones. Nadina tells me how Bosnia’s tiny Jewish community saved so many of their Bosniak neighbors during the (1990s) siege of Sarajevo [2]. This courageous movement was led by Jakob Finci, born in 1943, in a concentration camp on the island of Rab (now Croatia).

In 1892 — just fourteen years after Bosnia was occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire — a new wave of well-educated Ashkenazi Jews established La Benevolencija to underwrite higher education for a select group of Bosnian Jews. In 1992, under the auspices of La Benevolencija, Finci organized convoys to evacuate people desperate to escape yet another war.

16.

Looking at a photo of a synagogue that accompanies a 2017 news story about Finci, I peer beyond the bimah, beyond the graceful, scalloped arch and the mosaic tiles that adorn it. Finally, my eyes rest on the ark. Familiar, comforting. This synagogue, this sanctuary, merges with the ones I captured with my camera in Safed and Haifa and Jerusalem.

17.

December 12, 2021, Ha’aretz publishes an article by Esther Solomon that draws parallels between deniers of the Holocaust and the genocide in Bosnia. A 1993 photo accompanies this article. “Women and children, evacuees from the besieged Bosniak enclave of Srebrenica, packed on a truck en route to the UN ‘safe area’ of Tuzla on March 29, 1993. Their male relatives weren’t allowed to leave,” the caption reads.

18.

In the photo, the women’s and children’s faces carry fear. Scarves, like the one my grandmother wore each Friday night, cover the women’s heads. And even while this picture haunts me, I see the glow of candles and follow the circular movement of my grandmother’s hands as she welcomes in the Sabbath and sings the blessings. I add my own prayers now, for those who have perished, for those who have suffered, and for those who suffer still.

[1] The U.N.’s Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Margot Wallström, estimates there to be 50,000 to 60,000 cases.

[2] Currently, it’s estimated the Jewish population in Bosnia is no greater than 500, 85% of Sephardic descent.

Nominated for The Pushcart Prize, Best Small Fictions, and The Millions, Dina Greenberg’s writing has been published widely. With a research focus on trauma, she parlays her skills as a creative writing instructor, coach, and editor to give voice to survivors of war, displacement, and abuse. Her debut novel Nermina’s Chance begins in war-torn, 1992 Bosnia.