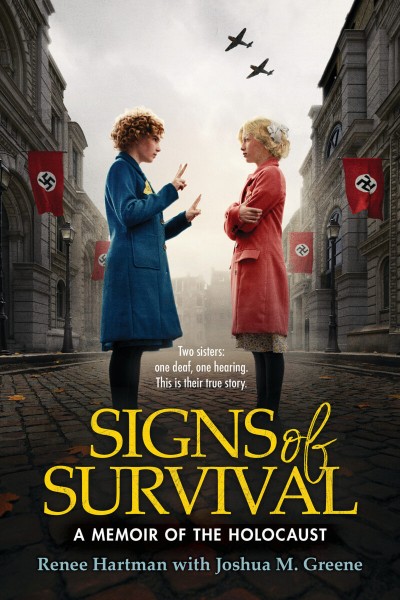

Herta, age nine on left. Renee, age ten and a half, on right. All photos courtesy of the publisher.

In 1944, ten-year-old Renee Hartman’s her family and community are rounded up and sent to Auschwitz; her one remaining relative is her deaf younger sister, Herta. This connection becomes more precious, her last link to normality and family.

When they first return from the farm where they were hiding for the past year, the sisters wander the streets of Bratislava and survive by eating garbage. They do not understand why they see no other Jews on the streets. Have they all been sent away to be killed? Renee wonders. I don’t want us to be the last ones alive. She takes her little sister by the hand, walks to the nearby police station, and announces they wish to join their parents. The police take them to the loading platform and put them in a cattle car filled with other Czech Jews. The sisters do not see their parents and are not aware they were already deported to Auschwitz and murdered. After a journey of several days with only one slice of bread each, Renee and Herta arrive at concentration camp Bergen-Belsen.

Today, Renee Hartman is nearly ninety years old and her sister Herta died last year, at age eighty-seven. In a recent interview, Renee describes that her most vivid memory of childhood is immersing herself in books, a habit that led in later years to her career as a poet and memoirist. Her story, Signs of Survival, is written for middle-grade readers and references both the sign language she used to communicate with her deaf sister and parents, as well as indicators that she was still alive in Auschwitz: ferociously protecting Herta from Nazi doctors, writing clandestine diary entries on a roll of toilet paper, learning words in Yiddish and Polish to gather information from other prisoners that alerted her to what to do and what not to do in order to survive. Renee does not recall the day of their liberation in April 1945. She was delirious from typhus fever and would not have survived, had British forces arrived a day later.

Memoirs such as Renee’s underscore, as no other documentation can, the individual human experience of the Holocaust.

Memoirs such as Renee’s underscore, as no other documentation can, the individual human experience of the Holocaust. It is a point of entry of particular importance for middle-grade students, who are old enough to begin forming an impression of the Holocaust. Stories of the Holocaust show the human spirit and also the failure of that spirit; these narratives show acts of heroism and also the unheroic acts Jew and other victims of the Nazis had to do just to stay alive.

Signs of Survival offers an added dimension for the education of middle-grade readers: the description of Renee’s time during the Holocaust absorbs only one-half of this short book. The second half documents Renee and Herta’s experiences arriving in America, such as the experience of seeing a person of color for the first time, and the startling discovery of “carts and wagons piled high with fruits and vegetables … a shocking contrast with the scarcity we had known in Europe.” She vividly remembers thinking, entering this new world, that “Not only did we have to get used to war, which was unbearable — but now we had to get used to peace, which was unbelievable.”

Particularly noteworthy is the episode that concludes her memoir. Now retired from their respective careers and their children grown into young adults, Renee convinces Herta to return with her to Bratislava. At the end of their visit, she signs to her deaf younger sister, “The Nazis sent us to Bergen-Belsen before we could have a real childhood. All we knew was war and suffering. I wanted us to come back here so that we could say goodbye and have some peace at last.”

In the 1970s, Renee and Herta videotaped their remembrances for the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University. The Fortunoff Archive is the oldest such initiative in the world and houses more than 15,000 hours of testimony. Signs of Survival is based primarily on words taken directly from the transcripts of their videotaped memories.

Joshua M. Greene produces books and films about the Holocaust. His documentaries have been broadcast in twenty countries and his books translated into eight languages. He has taught Holocaust history for Fordham and Hofstra Universities. He is also the coauthor of My Survival: A Girl on Schindler’s List by Rena Finder. He lives in Old Westbury, New York.