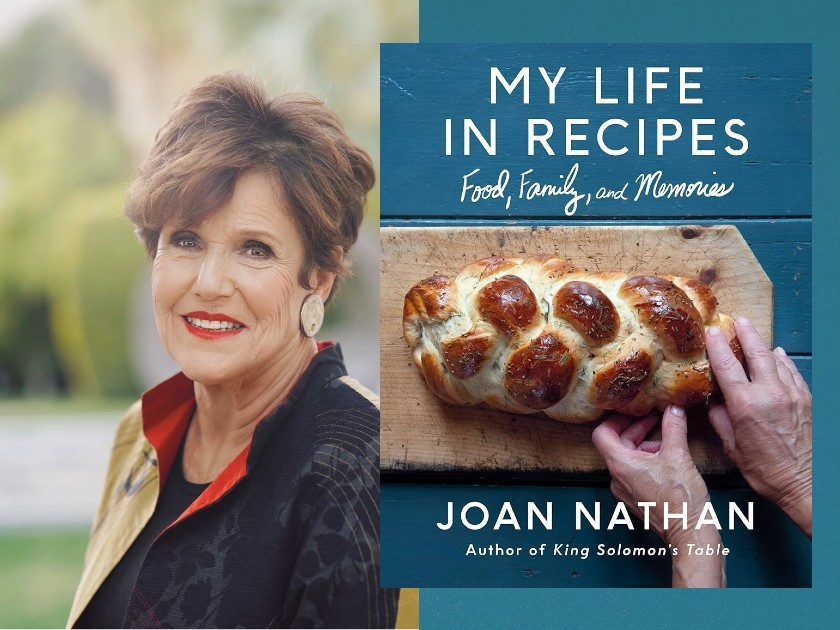

Author photo by Hope Leigh

Recently I had the opportunity to talk with Joan Nathan, the prominent writer on Jewish cooking, about her newest book, My Life in Recipes: Food, Family, and Memories, a warm collection of her personal and family life built around more than one hundred recipes.

Maron Waxman: When did the idea for the book start taking shape?

Joan Nathan: I thought King Solomon’s Table would be my last book, but my editor came to Washington for a visit. She looked around the house and the kitchen and saw everything I had saved over the years — letters, photographs, journals — and thought all that would make a book. So it was her idea.

MW: Food, Family, and Memories, the subtitle of the book, said a great deal to me. How did the formal title come about?

JN: The title was the editor’s. But “Recipes” was in my working titles. “Recipes” had to be in the title because recipes are what I do. The editor came up with the final title.

MW: Did you cook with your mother?

JN: I cooked a little with my mother. When I was growing up, we had a professional cook until my father’s business had a downturn, but once my mother started cooking, she loved it. I loved the recipes she made—Zwetschgenkuchen, a German plum pie, and rugelach. I cooked with my mother when I was older, not when I was young. I have memories of her making Zwetschgenkuchen, working the dough.

MW: The Flavor of Jerusalem was your first book, which you wrote with Judy Stacey Goldman. It started with the idea of inviting members of the foreign press and their wives into the homes of various cooks so they could get to know the people. How did you convince these women to have people come into their kitchens to watch them cook?

JN: We knew some of the women, and they trusted us. Remember, I was in Israel for three years and knew a lot of the cooks, so it was easier to persuade them to host the foreign press. Also I worked in the mayor’s office.

This started as a lark. We had no idea we would write a book. We wrote down all the recipes by hand and wrote down their stories with the recipes, then had the cooks review what we wrote. This is still my practice. The stories became the headnotes in the book.

When I started writing, I wrote by hand, then started using a typewriter. I’m a fast typist, so I could get everything down quickly. Then I moved to the computer, but I’ve never done any recording.

It took a long time to get the book published. Publishers didn’t think it was kosher enough. They had a narrow view of what Jewish cooking was.

MW: What connections do you see in the various Jewish food traditions?

JN: The connection between the different Jewish traditions is of course the laws of kashrut, Sabbath, and holidays. In addition the concept of looking for the new and adapting to local traditions as Jews wandered.

MW: Where do you think your taste for adventure comes from, especially adventure when it comes to all kinds of food? Was there ever a food or dish you didn’t want to sample?

JN: I think I was born with a sense of adventure. I do remember one time in Jordan when I was served a dessert I love, knafeh. This one was made with mutton fat, and I just couldn’t bring myself to eat it, not with mutton fat. I just nibbled at it and pretended to eat it.

MW: You were among the writers who practically invented the career of food writing. With so much emphasis on video now, will the profession change?

JN: Written recipes will always be important. The story approach connects people to culture and history and teaches them about this. Someone wrote an article in a small academic journal saying my book was the first time there were headnotes in a cookbook. Long headnotes are necessary to explain the story and context of a recipe.

Written recipes will always be important. The story approach connects people to culture and history and teaches them about this.

MW: Do younger people need videos to understand how to cook because they haven’t been brought up in cooking kitchens?

JN: Much of younger people’s lives are online, and it’s not a problem. Cooking shows on TV encourage them, and they can learn to cook from them. Young people have long lives ahead of them, and who knows how they’ll use this information. But online cooking does make it harder to find sources for family recipes.

MW: Do your children cook from the family recipes?

JN: My children do keep some recipes going. My daughter has no meat in the house, but she calls me with questions for latkes and dishes like that. And they do bake challah

I’m updating my Children’s Jewish Holiday Cookbook now. It’s coming out this fall, now titled A Sweet Year. I cook with my six-year-old twin granddaughters, and I love it.

MW: You have a real gift for family and friends, and I enjoyed meeting so many of them in the book. Do you and your guests linger at the table after the food is cleared and just continue the evening?

JN: I think I have an openness for much in life, and much in life is just luck. I have no idea of where my love of being a food writer came from. It just happened. I think my skill lay in taking advantage of opportunities. You never know what’s going to come up. My husband and I both had interesting jobs, and so we knew interesting people. My husband introduced many interesting people from politics, and I had to test recipes, so that was an opportunity to bring people to dinner. Friendships were nourished at the table, and yes, after dinner we did stay at the table.

I still have Shabbat dinners every week with a few people. I like it as a way of calming down and just being, of taking a pause in the week.

MW: At twenty-six you write that you wanted to have an interesting life. It sounds to me that you’ve accomplished that.

JN: At twenty-six my mother wanted me to get married. Who knows at twenty-six what’s going to happen? At that point I went to Israel, and it has shaped my life. I went back regularly and go every few years, sometimes more, sometimes less.

MW: Throughout the book and in all your work, you stress the importance of food traditions, especially Jewish food traditions, in your own family and in so many other cultures — French, Israeli, Moroccan, Middle Eastern, American — expanding the scope of Jewish food traditions and cultures, and I want to thank you for this.

JN: I appreciate that. In a recent edition of the Forward, an article listed 125 American Jews who had done something for Jewish culture, and I was among them. That seems right to me. Jewish Cooking in America made Jewish food easier for non-Jews who wanted to convert. It’s nonthreatening and helps non-Jews establish Jewish households.

Throughout my life, mostly I did what I did because I liked it.

Maron L. Waxman, retired editorial director, special projects, at the American Museum of Natural History, was also an editorial director at HarperCollins and Book-of-the-Month Club.