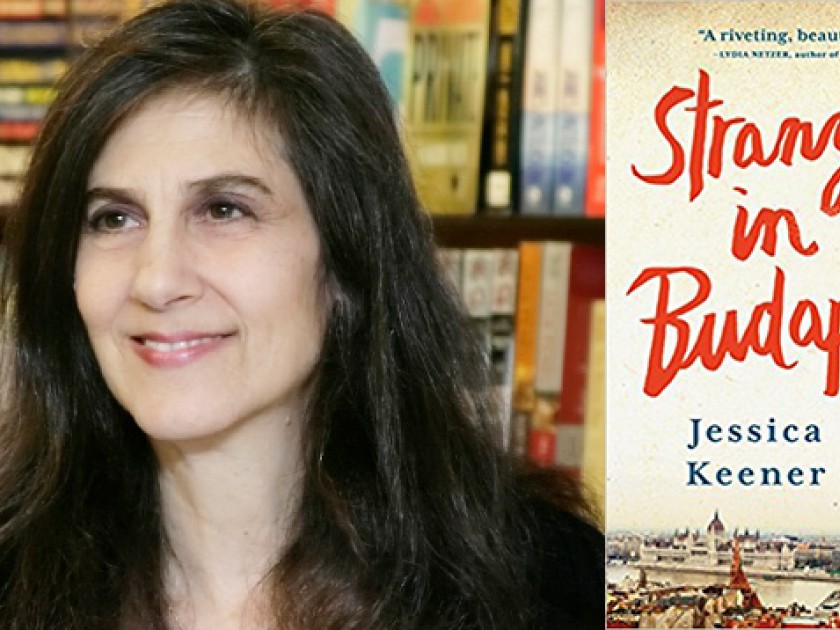

Jonathan Arlan recently spoke to Jessica Keener about her moody and captivating novel, Strangers in Budapest.

Jonathan Arlan: Annie and Will are Americans living in Budapest in the 1990s, not long after the fall of Communism. They are idealistic and hopeful about starting a new life in the city, and about the possibilities that could open up to them—there seems to be a boom happening all around, culturally and financially. Yet it remains just out of reach. What was it about putting these people in this very particular place and moment in time that appealed to you?

Jessica Keener: The mid-1990s were a unique time in Hungary. Because Communism was no longer the organizing structure for the country, there was a tremendous sense of freedom and release, but also of uncertainty and fear. When old structures are dismantled, what will replace them? When old ways are no longer the norm, what is the norm? My characters, Annie and Will Gordon, are also attempting to dismantle something in their lives and reach for something new and untried. They quickly learn that change is not so easy — it takes time and it’s evolutionary. Budapest, with its confluence of conflicting and opposing impulses, perfectly mirrored externally what I was trying to capture and reveal internally about my characters.

JA: You spent time in Hungary in the 1990s. What were your initial impressions of the city? How do you think those memories informed Annie and Will’s experience in the novel?

JK: I’m a Boston native, and when I visited Budapest for the first time, I was smitten by the similarities between the two places — the architecture of the buildings, the streetcar systems, the rivers that run through each city. Budapest has the Danube. Boston has the Charles. There are even paths that cut through the hills of my town in Brookline (which is just outside Boston) that are very similar to the ones in Buda, the hilly side of Budapest. When I was living in Budapest, many of the buildings were riddled with bullet holes. It was a constant reminder of human destruction. I visited the Jewish district and was haunted by the old synagogue that was empty and in disrepair. (It has since been renovated.) At the time, no one talked about the Jews or how the country sent 800,000 Jews to death and work camps. This haunted me for many reasons, but foremost because my father fought in World War II and his army division helped liberate Dachau. I created Annie and Will to explore one way in which people manage their lives after experiencing or witnessing violence.

JA: Have you been back to Budapest since?

JK: No. But, now that my novel is finished and out in the world, I would love to return. It’s a beautiful city. The synagogue has been restored. There’s a memorial on the Danube that honors the lives of Jews slaughtered on the riverbanks of the river during World War II. I want to see those changes and more. At the same time, I’m concerned about the political shifts going on there. Humanity is messy.

JA: The Jewish underground movement is a fascinating chapter in the long history of Jews in Hungary. In the novel, two Hungarian friends of Annie and Will had been involved in the movement during World War II and are now living in the United States.How did you first learn about the underground? Why was it important to incorporate this piece of history into the book?

JK: When I was living in Atlanta, I met an older Jewish woman, Hannah Weinstein Entell, who had worked for the underground, providing food for prisoners of war. Hannah was born in Vienna and escaped Austria in the 1930s. I was taken by Hannah’s zest for life, her positive energy, her interest in people, and her fortitude. She also introduced me to George Friedmann, a Hungarian Jew who escaped the Germans during World War II. He, too, had an amazing life force that inspired me. In my novel, there is a minor character, Rose, who once worked for the underground and sets things in motion for Will and Annie. I incorporated this aspect of history into my novel as a reminder that people are complicated and not what they appear to be on the surface. People who have lived through unthinkable struggles and walk by us every day. As a Jew, I feel an acute awareness surrounding this idea of hidden stories.

As I wrote, I thought about all the immigrants who have come to America to escape oppression. My grandfather came through Ellis Island in order to escape the Russian Czar, and I exist because of this decision my grandfather made. It takes enormous courage to speak up, to risk your life and flee. My character Edward Weiss is a fighter for justice. He is in pursuit of the truth. I wanted readers to encounter someone like Edward in my book and think about how difficult it is to actually stand up and take action against wrongdoing.

JA: The relationship between Annie and Edward is both tender and, in some ways, tragic. What do you think they see in each other?

JK: Recently, at an author event, a person in the audience observed that both Annie and Edward drink a lot of water in the novel. (My novel takes place in the summer and heat is a factor.) The person commented that she thought Annie and Edward were both thirsting for life. Without giving away plot points, I think Annie is drawn to Edward because he’s able to tap into her life force — her most authentic self — something she found hard to do. Edward is drawn to Annie because there is something about her that reminds him of his dead daughter. Getting to know Annie is Edward’s second chance to love his daughter with more empathy and compassion, something he failed to do when she was alive.

JA: At one point, you draw an interesting comparison between Vienna and Budapest — both former capitals of the Austro-Hungarian empire. You write, “In Austria, remnants of greatness left imprints like fossils.” In contrast, Budapest is messy, worn-down, and full of energy — it is taking risks. Was the novel always set in Budapest? How different do you think it would have been if you’d set it in Vienna?

JK: The novel was always set in Budapest and truthfully I could not envision my story set anywhere else — certainly not Vienna. This is because Vienna is a much different place. It has immense wealth. It dominated Europe at one point. Austrians speak German, not an uncommon language globally. Hungary is much more insular because of is language, which most people don’t know. Budapest is like the poor country cousin to Vienna. It has to prove more to the world in order to be heard and recognized. At the same time, Budapest is more mysterious, intriguing, and haunting — that word again. This is the atmosphere I wanted to capture in my novel.

JA: I’m curious about Annie and Will, Edward, and Stephen. They are very different people, from completely different backgrounds — different generations, different countries. But they’re thrown together in this story in a way that feels organic and almost inevitable. How did these characters come together for you?

JK: I’m glad you asked this question. I wanted my story to be multigenerational, to encompass the life cycle from young to old. It’s why I also have a baby in the story (Annie and Will’s infant son). I wanted to show that history is something that is passed on in our personal, domestic lives as well as our cultural and social lives. I’m also interested in what people can learn from each other despite differences in age, religion, or experience. Often we learn the most when we meet someone we think is very different than who we are. Usually, we find the common denominator through a meeting of the heart. My characters are different on the outside, yet they are each pushing hard to come to terms with who they really are.

JA: What are you working on next?

JK: A novel set in Boston, in present time, which deals with spirituality, marriage, and love.

Jonathan Arlan is a writer and editor currently based in Kansas City. He is the author of the recently published travel memoir Mountain Lines: A Journey through the French Alps.