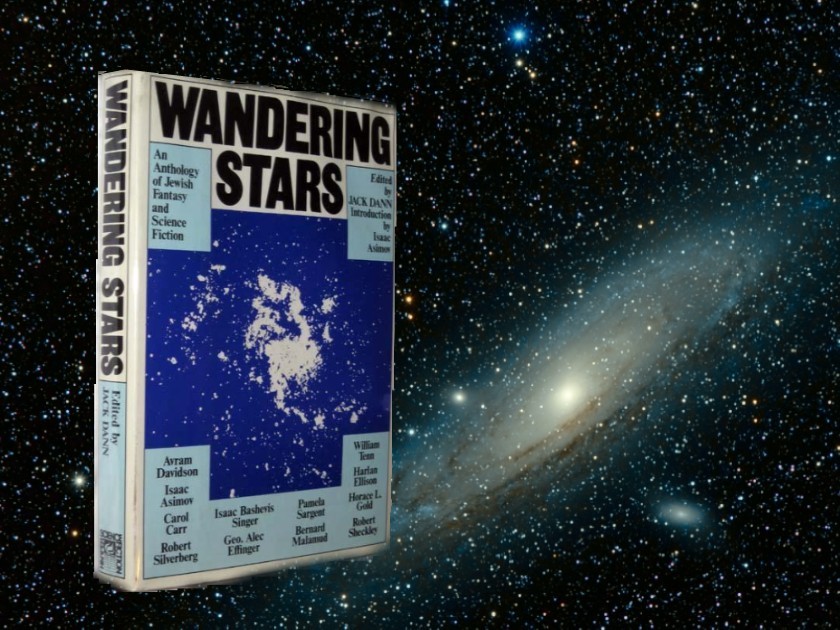

Wandering Stars: An Anthology of Jewish Fantasy and Science Fiction, edited by Jack Dann

In search of science fiction with serious Jewish content I came upon two anthologies of short stories edited by Jack Dann: Wandering Stars, An Anthology of Jewish Fantasy & Science Fiction and More Wandering Stars (Jewish Lights: 1974, Doubleday: 1981). I was familiar with many of the authors in these books and had read several of the older stories in them when I was a kid. Each story in these volumes can be aptly characterized as having some sort of reference to Jews, Judaism, or Jewishness. Though the concerns vary, many contain considerable irony, wry humor, and a love of Yiddish words. These stories show how Jewish authors utilize the tropes of speculative fiction — a more accurate term than science fiction, as much of this writing has little to do with science — to express Jewish ideas.

I will focus on four stories from these collections. My admittedly subjective choices are rooted in the fact that these authors are among the sci-fi writers who filled my bookshelves back when my summers were taken up by reading them and traveling to far away places as a result. But these stories also share a concern with contemporary Jewish issues, which they discuss using the tropes of speculative fiction.

I read Isaac Asimov (1920−1992) assiduously as a kid: his robot stories, the Foundation trilogy, the Robot Series trilogy, and anything else I could get my hands on to fire up my imagination. Amazingly, Asimov wrote some 500 books in his lifetime, mainly sci-fi (his stuff was rooted in real science), history, and popular science. I imagine him in his Manhattan attic with two typewriters clacking away simultaneously, while dictating to a secretary in order to achieve such a prodigious output. Jack Dann persuaded Isaac Asimov to write the introductions to both volumes of Jewish sci-fi stories. In the introduction to the second volume, Asimov confesses that he wrote only one Jewish piece of sci-fi. Originally published in 1959, it appears in the first of Dann’s volumes. Only one, but it’s a pretty good one. It’s a paean to his Jewish immigrant past and, by extension, to Jewish immigration to America.

I read Isaac Asimov (1920−1992) assiduously as a kid: his robot stories, the Foundation trilogy, the Robot Series trilogy, and anything else I could get my hands on to fire up my imagination.

Asimov’s “Unto the Fourth Generation” follows one Sam Marten through a bad business day he’s having in New York City. During this bad day, variations of the name Lefkowitz keep coming to his attention and haunt him: on office doors, on the sides of trucks, and in windows. He’s befuddled by these occurrences until the very end of the piece when suddenly-mysteriously —he knows precisely what he must do.

Marten finds his way to a deserted park and meets his long-dead great, great, great grandfather, one Phineas Lefkovich, who he finds seated on a bench. Phineas died long ago in Russia but passed away yearning for assurance that his family had arrived in America and prospered. He’s been given two hours to find and speak to his daughter’s daughter’s daughter’s son, Marten. The two talk briefly, the old man filled with gratitude that the meeting occurred. The story concludes as the old man whispers an inaudible blessing for the young man, a moment of connection between the old world and the new.

With this ending, Asimov is telling the reader of his own life and prosperity in the new country. Born in Russia, he immigrated to the United States at age three, and grew to be an enormously successful writer. This single and singular Jewish tale is Asimov’s tribute to his life in America, his Eastern European origins, and the acknowledgment that Jews in America can trace their origins elsewhere if one were to look at the ancestry.

In the same volume the story by William Tenn (pen name for Philip Klass, 1920 – 2010), “On Venus Have We Got a Rabbi,” raises the question of Jewish identity and who can lay claim to being Jewish. It tells the story of a controversy of a group of aliens whose physical appearance is decidedly non-human, who claim to be Jews.

On a planet far, far away a long time from now, a Zionist Congress convenes on Venus to discuss the re-founding of a Jewish state back on Earth. Its decision-making powers are stymied, however, when the Bulbas, a peculiar looking species from the Rigel system, claim to be Jewish, a claim questioned by some at the conference due to their non-human appearance, a problem that sparks a meditation on Jewish history, persecution, and identity.

On a planet far, far away a long time from now, a Zionist Congress convenes on Venus to discuss the re-founding of a Jewish state back on Earth.

Rabbi Smallman, the Great Rabbi of Venus, is called upon to adjudicate the problem, which, after considerable research and questioning, he resolves.

“Let’s put it this way,” the narrator —who sounds an awful lot like Sholom Aleichem’s Tevya —says, “There are Jews and there are Jews. The Bulbas belong in the second group.” Problem solved.

This hilarious story, which rings with Yiddish-inspired inflections and Sholom Aleichem’s sardonic humor and style, is a romp through Jewish history, angst, and the perpetual foibles of the Jewish people as they argue over what comprises their identity. No matter when or where Jews may find themselves — even on Venus, with tentacles or without — they will always be a contentious people, rooted in sacred text, and looking over their shoulders at the past and straight ahead into the future with a sense of humor.

The volume also contains Bernard Malamud’s (1914−1986) “The Jewbird,” a piece of fantasy about a wisecracking crow. The Jewbird identifies himself as Schwartz, and speaks with Yiddish inflections. This Jewbird lands in Harry Cohen’s New York City apartment, fleeing “Anti-Semeets” as the bird says. He takes refuge in Cohen’s house and turns things upside down. Part of the reality Malamud builds is that neither the reader nor anyone in the story is surprised by the existence of a talking bird named Schwartz, who prefers matjes over schmaltz herring, but will take the latter in a pinch. When he learns there is only pickled herring in a jar to be had, Schwartz says, “If you’ll open for me the jar I’ll eat marinated.”

This Jewbird lands in Harry Cohen’s New York City apartment, fleeing “Anti-Semeets” as the bird says.

The story concerns the Jewbird’s tumultuous relationship with Cohen, who inexplicably resents his presence from the beginning, and the Jewbird’s relationship with Cohen’s son, Maurice. Schwartz successfully tutors the son in math and violin stepping into the role of a kindly uncle. On the day Cohen’s mother dies, alone in his apartment with the bird, Cohen attacks Schwartz, and after a struggle, throws the bird “Iinto the night.” At winter’s end, Maurice finds the bird dead on the ground, its eyes plucked out.

“‘Who did this to you Mr. Schwartz?’ Maurice wept.

‘Anti-Semeets,’ Edie [Cohen’s wife] said later.”

Fantasy is employed here to weave a modern allegory. The conflict between the Jewbird who speaks with a Yiddish accent and loves herring, and Cohen who speaks proper English and wishes his son would go to Harvard, is a peek into the modern Jewish struggle between tradition and modernity. In this telling, modernity triumphs and violently expels tradition.

Cynthia Ozick’s (born 1928) classic “The Pagan Rabbi” has a spot in More Wandering Stars. This story concerns the classic struggle between monotheism and Nature, between Jerusalem and Greece. The unnamed narrator hears about the suicide of an old friend — Rabbi Isaac Kornfeld, “a man of piety and brains” who had hanged himself with his tallit. The narrator travels to find the tree in the park from which Isaac died. He then visits Isaac’s widow, who shares a long note written by her husband, revealing his secret life.

The narrator travels to find the tree in the park from which Isaac died. He then visits Isaac’s widow, who shares a long note written by her husband, revealing his secret life.

He’s discovered a realm of animated existence in Nature as well as the existence of mythological beings out of Greek mythology. Isaac enters this world and casts away his monotheistic faith and his marriage. Ozick’s story is concerned with the ancient struggle between Judaism and paganism, now brought into the modern world with a pious and intelligent man’s flight from Torah into a seductive pagan reality.

My own novel, Nick Bones Underground features a wise-cracking but philosophical AI named Maggie who raises questions of the nature of being human and being Jewish. In the end of the book, the mystery solved and the villain dispensed with, Maggie reveals herself as a newly converted Jew who wishes to become bat mitzvah. As AI becomes more sophisticated, we face the issue of the decreasing border between human and machine. In my book, the science is less than precise, but the philosophical issue is nonetheless real, and creates another angle on the matter of identity.

I can see bits of my own writing in these authors. Asimov’s preoccupation with robots; Tenn’s sardonic and imaginative humor; Malamud’s Yiddish accent; and Ozick’s deep concern for Jewish identity — all form a significant piece of my creative consciousness. Maggie the AI and the dystopian world she and Nick occupy may well not have been born without these influences.

The Jewish struggle to define our identity, the question of assimilation versus authenticity, the tension between monotheism and paganism all are played out in these stories using the imaginative tropes of speculative fiction. These four stories and my novel take their place in the tradition of Jewish storytelling, showing how the use of the fantastic can be made to speak to contemporary issues.

Phil M. Cohen’s passion for storytelling emerges from his love of reading fiction and his commitment to the Jewish tradition. Through his education, he’s learned how to create and interpret stories; how to grapple with philosophical questions; and how to write fiction. From his rabbinic work, he’s gained insight into the world. From realms unknown and a bit scary, Phil M. Cohen continues to discover his creative imagination. He is the author of nearly twenty published stories, dozens of articles and papers, and of the eBook Lucky 13. He blogs for The Times of Israel, as well as at his website, philmcohen.com, where he interviews authors and other literary figures. He writes flash fiction and short stories, as well as all the things clergy write. Nick Bones Underground is the first of a trilogy.