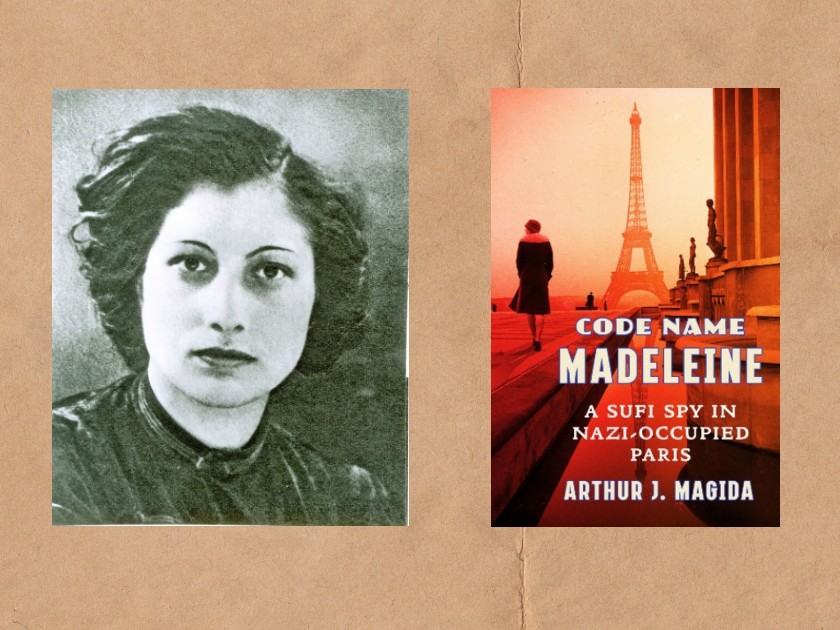

Photo of Noor Inayat Khan, Code Name Madeleine

Noor Inayat Khan, the focus of my book, Code Name Madeleine, was a most unlikely secret agent of World War II: a Sufi, or Islamic mystic, and an acclaimed poet, musician, and writer of children’s stories, Noor was recruited by Britain’s top-secret Special Operations Executive (SOE), then survived in occupied Paris three times longer than most other agents from the same agency. Engaged in what she called “the joy of sacrifice” to defeat the Nazis and save Jewish lives, Noor was executed at Dachau; defiant to the end, her last word was “libertè.”

Noor’s mother, Ora, was American. Her father, Hazrat Inayat Khan, was Indian and introduced Sufism to the West in 1910. Noor herself was born in Moscow in 1914, then raised in a village opposite Paris. She matured into a strong willed young woman, who invariably put others before herself; service was a bedrock of the creed she inherited from her father. “The essence of mysticism,” Inayat taught, “is readiness to serve the person next to us… To become an angel,” he continued, “is not very difficult,” but living in the world, with “all its difficulties and struggles, and being human at the same time, [that] is difficult. If we become that, then we become the miniature of God on earth.” For father and daughter, spirituality did not hinge on retreating to an ethereal, distant realm. It was here and it was now.

When the time came to serve during World War II, the SOE flew Noor into Europe the night of June 16th, 1943. Noor was the SOE’s first female radio operator in France. Constantly on the run, she held the Gestapo at bay while never straying from the demanding ethics she had learned from her father: “Bear no malice against your worst enemy.” “Do not neglect those who depend upon you.” “Do not spare yourself in the work which you must accomplish.” When Noor was finally caught, she told the Germans nothing of value, winning their respect even while trying to escape twice—the first time by balancing on a rain gutter five floors up on the façade of a Gestapo prison in the middle of Paris. After Noor’s second escape attempt, she was sent to a prison in Germany—imprisoned in solitary confinement and in chains, wrist to wrist and ankle to ankle. Ten months later, she was killed at age thirty.

Noor was the SOE’s first female radio operator in France. Constantly on the run, she held the Gestapo at bay while never straying from the demanding ethics she had learned from her father.

Noor defied everyone’s expectations — the British and the Germans. One SOE trainer said she was “not overburdened with brains.” Though Noor had more than her share, the trainer was certain Noor lacked the reflexes and ingenuity to outwit the Germans for even the scant six weeks of the average radio operator in France. When another trainer warned Noor that she might reveal secrets if the Gestapo tortured her, she came up with a simple solution: she would remain silent. She didn’t quite stay quiet, but the Nazis never gained anything useful from her. And though the Gestapo had its own version of “honor,” it was no match for Noor’s. Hers rested on compassion, truth, courage, and the sacredness of life; theirs rested on an unyielding loyalty to Hitler.

Noor sent invaluable information to London on the thirty-pound radio which she lugged around Paris — some of it key to the success of D‑Day, still a year away. Her motivation was simple: she abhorred Nazism in general and its extermination of Jews in particular. That’s why I’m convinced a phrase she wrote in the late 1930s sums up her reason for fighting the Germans: “The heart must be broken for the real to come forth.” The war broke Noor’s heart, and the real came forth, a “real” of pain, devotion, and a higher and better articulated calling than what animated most agents.

Noor’s spirituality allowed her to embrace the jostle and the annoyances of the world, and to withstand its horrors. For her, these were indispensable to life, and she never pushed away life. This was similar to how Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel — activist and friend of Martin Luther King Jr. — would later describe those who are spiritually and socially aware. Such individuals, said Heschel, combine “a very deep love, a very powerful dissent, a painful rebuke, with unwavering hope.” Hope was Noor’s banner. She carried it so humanity could redeem itself.

Sufis hold a memorial service for Noor every September at Dachau, a few hundred feet from the crematorium where her body was incinerated in 1944.

Noor’s dedication to fighting for life is inspiring. The abrupt and early end of her life is tragic. Yet the fullness of her thirty years can remind us of our potential to be fully human, and fully compassionate, even in the most trying of circumstances. That’s one reason why Sufis hold a memorial service for Noor every September at Dachau, a few hundred feet from the crematorium where her body was incinerated in 1944.

I’ve been invited to speak there this fall. If the pandemic eases and I’m allowed into Europe, I’ll mention a Chasidic saying: “If you want to find a spark, sift through the ashes.” More than seven decades after the war, there are ashes at Dachau. I know — I’ve been there. But there are also sparks — Noor’s and thousands of others who were killed there. The ashes are the weight from the past; the sparks are how they illuminate our present.

Noor urged us not to turn our back on life. “Life,” she said, “is a struggle and we must be ready to struggle.” Let the struggle begin, one that is no different than what inspirited a young Sufi woman and what Pirkei Avot espouses: “Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly now. Love mercy now. Walk humbly now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.” Noor never abandoned her work. The world is a better place for that.

Code Name Madeleine has been nominated for a Pulitzer and optioned for a film

Arthur J. Magida has been nominated for a Pulitzer and won multiple awards. His last two books—Code Name Madeleine (“absolutely gripping,” “tightly plotted”) and The Nazi Séance (“an astonishing story, brilliantly told,” “haunting, vivid”) — are optioned for films. He’s been a contributing correspondent to PBS’s Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, senior editor of The Baltimore Jewish Times, and editorial director for Jewish Lights Publishing. He lives in Baltimore.