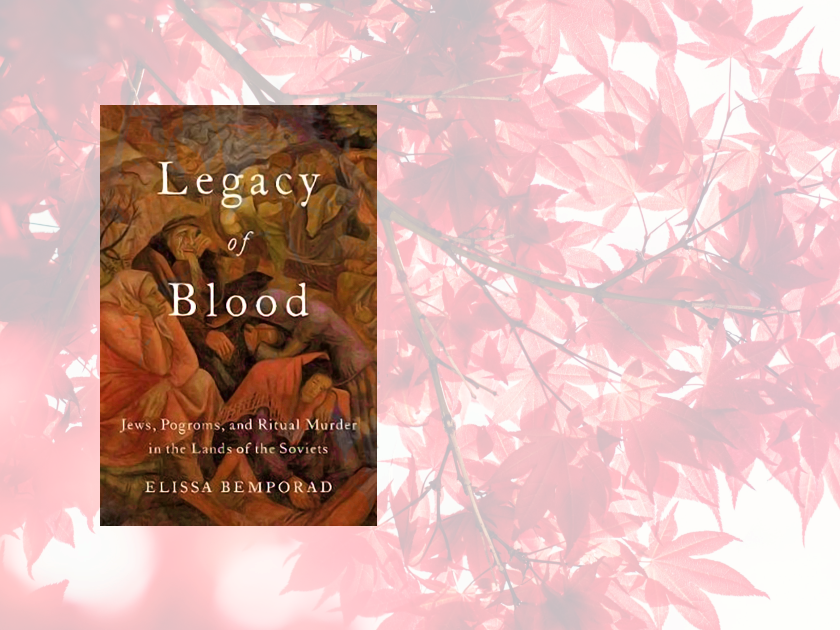

Legacy of Blood: Jews, Pogroms, and Ritual Murder in the Lands of the Soviets tells the story of the afterlife of pogroms and blood libels — the two most extreme manifestations of tsarist antisemitism — in the Soviet lands from 1917 to the early 1960s. Pogroms and ritual murder were often closely intertwined in history and memory, not least because the accusation of blood libel — the false allegation that Jews murder Christian children to use their blood for ritual purposes — frequently triggered antisemitic violence. Such events were, and are, considered central to the Jewish experience in late imperial Russia; for example, the 1903 pogrom in Kishinev, the 1911 Beilis Affair in Kiev with a blood libel accusation that spiraled into a pogrom in Kishinev, and a ritual murder accusation against Menachem Beilis which almost led to a pogrom. The Soviet regime boasted its break from Tsarist Russia, and proudly claimed to have eradicated these forms of antisemitism.

But as I have discovered researching and writing this book, life was much more complicated. The phenomenon and the memory of pogroms and blood libels in different areas of interwar Soviet Union, including Ukraine, Belorussia, Russia and Central Asia-as well as, after World War II, in the newly annexed territories of Lithuania, Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia, are a reminder of continuities in the midst of revolutionary ruptures. The persistence, the permutation, and the responses to antisemitic violence and memories of violence suggest Soviet Jews (and non-Jews alike) cohabited with a legacy of blood that did not vanish.

The persistence, the permutation, and the responses to antisemitic violence and memories of violence suggest Soviet Jews (and non-Jews alike) cohabited with a legacy of blood that did not vanish.

Let me dwell on the pogrom thread of the book, a term that has cast a dark shadow over Jewish history, and tell you how I came to explore the legacy of antisemitic violence in my research. The power of the archives, the extent to which the material we uncover in our journey through these spaces shapes the narratives we create as historians, inspired me to write Legacy of Blood. A few years ago, thanks to the support of a fellowship, I spent a year off from teaching and was able to devote some time to one of the most extraordinary archives on twentieth-century Jewish life in Eastern Europe (and beyond); namely the Elias Tcherikower collection held at YIVO, the Institute for Jewish Research. While looking for snippets from the Soviet press, specifically publications in Ukrainian and Russian that could shed light on the everyday life of Jews in the Soviet Union, I found the pogroms. Jewish historian Elias Tcherikower had made it his mission to collect and record the materials about the pogroms of the Russian civil war, an unprecedented wave of antisemitic violence that followed the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 and ended in 1921. Tcherikower defined the pogroms of the civil war as “one of the worst catastrophes that has ever shaken the fate of the greatest Jewish center in the world…which was devastated, shattered into pieces, and broken in its economic foundation.”

More specifically, I found the pogroms in the witness accounts and materials collected by one woman: Yiddish writer Rokhl Faygnberg.

More specifically, I found the pogroms in the witness accounts and materials collected by one woman: Yiddish writer Rokhl Faygnberg. She was born in Liuban (today Belarus), moved to Warsaw, and then settled in Odessa right before World War I. She had experienced the horror of the civil war pogroms. In the summer of 1919, when the violence reached its peak, Faygnberg fled in haste her home in a shtetl, located between the cities of Balta and Odessa, in southwestern Ukraine. Holding her newborn son in her arms, she went into hiding among the peasants of the nearby villages. A woman helped her disguise herself: she gave her a folk dress with the national colors, and a little cross to put around her child’s neck. Faygnberg eventually reached Odessa. As she later wrote, “[J]ew-murderers were still roaming around the Balta roads, and signposts were still hanging from the telephone poles, calling on people to kill all little Jewish boys, because when they grow up they will all be communists.”

There was something new and unparalleled in these pogroms compared to previous waves of antisemitic violence. As a refugee, Faygnberg recorded the experiences of others who, like her, had suffered during the civil war. She chronicled the brutality of the pogroms by zooming in on the destruction of a number of small towns. More than the authors of other accounts, Faygnberg captured the intimacy of violence in these pogroms. She reminds us that they originated not only within the military carried out by troops fighting or looting on behalf of the White forces — the Ukrainian Directorate, peasant bands, Polish troops, anarchists or Red Army troops — but that they were also the consequence of neighbors killing neighbors. n the aftermath of World War I, new forms of extreme brutality tapered the inhibition to kill and witness murder.

Reading the Russian version of the chronicle of Dubovo’s destruction guided me to ponder the legacy of these pogroms for Soviet Jews, the second largest Jewish community in pre-Holocaust Europe.

In the archives I found Faygnberg’s chronicle of the pogroms in Dubovo, a shtetl located a few kilometers from the city of Uman; the father of Hebrew writer Micha Josef Berdyczewski had served as rabbi of Dubovo for decades before being murdered in the 1919 pogrom. Faygnberg interviewed survivors and described how the shtetl’s population was wiped off the map of Ukraine; she also captured how, at the end of the civil war, the memory of Jewish Dubovo was completely erased, as the local peasants destroyed the Jewish cemetery, ploughed up and sowed it, tearing down its gravestones. Faygnberg’s account in Yiddish was eventually published in Warsaw into a book in 1926. I was surprised to find out that the book was later translated into Russian, and published in the Soviet Union in 1928. Reading the Russian version of the chronicle of Dubovo’s destruction guided me to ponder the legacy of these pogroms for Soviet Jews, the second largest Jewish community in pre-Holocaust Europe. How did the extreme violence of the pogroms, of the Russian Civil War, affect the choices made by those Jews who could not — or did not want to — flee the new Communist regime? How did the memory of the pogroms affect their identity and interact with the memory of pre-revolutionary antisemitic violence? And how was this violence commemorated by the Soviet state and its citizens?

While thousands of Jews, like Faygnberg herself, managed to get out of the territories that would come under Soviet rule, most of those who experienced the 1,500 pogroms of the civil war remained, and cohabited with the trauma of 150,000 Jews murdered, hundreds of thousands wounded, 300,000 children orphaned, thousands of women raped, and property looted or destroyed in its entirety; his experience of violence had not been integrated into the study of the Soviet Jewish experience, into the study of the ways in which Jews acculturated, assimilated, and Sovietized under Communism. This trauma left an indelible imprint on Soviet Jews’ relationship with the Bolshevik state, with their neighbors, and shaped new communities of violence and communities of memory. This experience remained a founding one for Soviet Jewry especially against the backdrop of a new society that saw the virtual disappearance of pogroms.

Elissa Bemporad is the Jerry and William Ungar Chair in East European Jewish History and the Holocaust, and professor of history at Queens College and The Graduate Center — CUNY. She is the author of the award-winning Becoming Soviet Jews: The Bolshevik Experiment in Minsk (Indiana University Press, 2013, National Jewish Book Award, Fraenkel Prize in Contemporary History, and runner-up Jordan Schnitzer Prize in Modern Jewish History). Elissa is the co-editor of two volumes: Women and Genocide: Survivors, Victims, Perpetrators (Indiana University Press, 2018); and Pogroms: A Documentary History of Anti-Jewish Violence (forthcoming with Oxford University Press, with Gene Avrutin). She has recently been a recipient of an NEH Fellowship and a Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC. Elissa’s projects in progress include research for a biography of Ester Frumkin, the most prominent Jewish female political activist and public figure in late Imperial Russia and in the early Soviet Union; and the first volume of the six-volume history entitled A Comprehensive History of the Jews in the Soviet Union, which will be published with NYU Press. Elisssa’s new book, entitled Legacy of Blood: Jews, Pogroms, and Ritual Murder in the Lands of the Soviets, has just appeared with Oxford University Press.