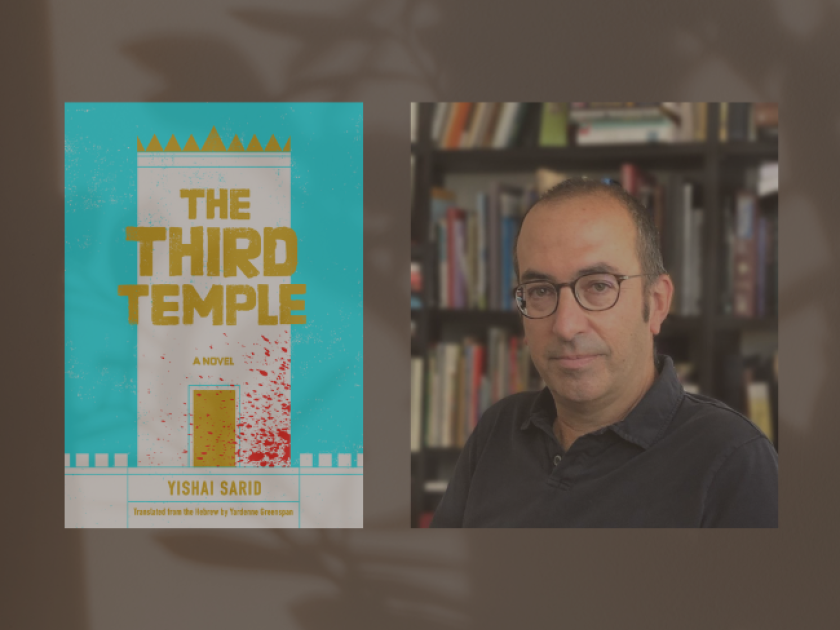

Author photo by Yasmin Sarid

Yishai Sarid is an award-winning Israeli author who has written seven books, many of which cast a keen eye on Israeli society. In this wide-reaching conversation, Sarid speaks with author and Judaic studies professor Ranen Omer-Sherman about The Third Temple, the latest of Sarid’s books to be translated into English. They also discuss how Sarid creates characters, how messianic ideologies threaten democracy, and what apocalyptic fiction can reveal to us about the present moment.

Ranen Omer-Sherman: Yishai, I’m a big fan of your edgy, startling windows into Israeli society, including your newly translated novel The Third Temple, which won the Bernstein Prize and earned praise for its unsparing rendering of a postapocalyptic Middle East. Students in my Holocaust course are always shaken by The Memory Monster, your disquieting work about the uses of Holocaust remembrance and pedagogy. And Victorious is such an utterly haunting character study of a morally compromised woman whose healthy libido, black humor, and acerbic observations help her to cope (up to a point) with Israel’s troubling realities.

Your novels grapple with the tremendous collective weight of memory, history, and obligation on your protagonists. In one form or another, those characters seem to suffer a psychic collapse or meltdown. Do you see yourself in the lives of your protagonists, or are they always at a safe remove from your own identity?

Yishai Sarid: Many thanks for your kind words and clever insights into my books. This is a good opportunity to credit my talented translator, Yardenne Greenspan, and Restless Books, my US publisher. I always see myself in the lives of my protagonists. I share their thoughts and feelings and sometimes also some biographical elements. I always place them in extreme situations where they need to fight for their lives or save their souls. However, their lives are much more adventurous than mine; I have this old-fashioned love of adventure books. At the same time, I try to keep some distance from them, which enables me to watch over them with irony and criticism. That is very important. I think writing about these people, who are both close to me and imaginary, helps me stay sane and not collapse. They are my sacrifice.

ROS: The Third Temple imagines the destruction of Tel Aviv and Haifa, a subsequent messianic enterprise to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, and Israel’s transformation into a “purified” theocratic kingdom rid of its secularism. Haaretz has called this book “the most apocalyptic, futuristic, historical” and “most realistic novel published in Israel in recent years.”

I felt that certain passages read as if they’re reflections of a future that is all too near:

The siege placed on our kingdom by the nations of the world made things difficult for scientists. The people’s security and survival needs were many, and they always took precedence over research. The schools … needed to focus on the urgent task of children to love the Torah … so science was cast aside. Many scientists therefore fled the country to the fleshpot of diaspora.

This is obviously a very frightening novel, perhaps because that “reality” the Haaretz critic alludes to seems even closer today than when the novel came out in Israel in 2015. How did the idea for this book come about? And how did you research it?

YS: This book stems from two places. First, during my childhood, I was fascinated with the Bible stories set in the Temple, where a real image of God lives among all the mysterious rites of sacrifice. It always seemed to me a great setting for a novel. The second root of this novel is my realization that Israel is moving fast toward a religious, nationalistic system, for which the rebuilding of the Temple is the ultimate desire and objective. I wanted to write a Jewish tragedy, telling the story of the last months of this fulfilled fantasy.

ROS: Modern Hebrew writing began with utopian thinking and the consolations of rebirth after the long centuries of exile and trauma. So it’s striking that Israeli literature has developed its own tradition of apocalyptic and dystopian literature, almost as if Israeli fiction writers are caught up in imagining a future Holocaust of some kind (or perhaps our own inauspicious present). Amos Kenan, a harsh critic of Israeli politics, wrote Hebrew literature’s most famous apocalyptic novel, The Road to Ein Harod, just a few years before the outbreak of the First Intifada. In Kenan’s dystopia, the protagonist rebels against a military junta that seizes power and proceeds to “cleanse” the country through the murder of liberal dissidents and Arabs (a sensibility that seems shared by the king and his messianic subjects in The Third Temple). In the 1990s, Orly Castel-Bloom was writing novels like Dolly City that were perhaps more playful, but certainly no less dark than Kenan’s. And Nava Semel’s And the Rat Laughed features a futuristic catastrophe that results in a pathologically distorted society. Even Amos Oz channeled certain anxieties about destruction in his novella Late Love. Do you see The Third Temple in any way participating in or responding to this dark literary undercurrent?

YS: When The Third Temple was first published in Israel in 2015, some people didn’t understand why I chose this subject, or why I was considering it through the lens of science fiction. But I already saw very clearly the cultural and social mechanisms that could lead us to this kingdom of Judea and replace the State of Israel. Nowadays, the same people ask me how I saw those things back then, and if I can stop this process from being fulfilled … so for me this book portrays a reality already being created. All the books you mentioned are built on the understanding that the existence of Israel is fragile, and especially its existence as a free and liberal democracy. This fear is stronger now than ever.

ROS: For many months, tens and sometimes hundreds of thousands of mostly secular Israelis protested on the streets of Tel Aviv and elsewhere, infuriated that Netanyahu’s government of religiously zealous acolytes is threatening Israel’s fragile democracy, ignoring the plight of the hostages in Gaza, and prioritizing messianic fantasies over the difficult territorial compromises that might achieve peace with Palestinians in the West Bank. To many, it appears that Netanyahu is in thrall to some greater messianic calling rather than interested in ensuring that Israel remains a safe haven for its people. Given the role of Itamar Ben-Gvir, Bezalel Smotrich, and other extremists in the government, how much of a challenge was it for you to get into the head of Prince Jonathan, the narrator of The Third Temple, whose father abolishes the Supreme Court, resurrects the Great Sanhedrin, and consecrates the messianic kingdom of Judah? He is a figure that might be easy to ridicule, but you clearly endow him with moral qualms and other sympathetic qualities, such as his empathy for the animals he sacrifices at the prophesied rebuilt Temple (on the other hand, he does not seem overly concerned with the suffering of children who are born with birth defects after the event known as the “Evaporation” and prohibited from approaching the Temple).

YS: I didn’t conduct special research about the minds and ideology of messianic people, because we are surrounded by them all the time, and they are the most influential group in Israel’s politics, society, and culture nowadays. They took some elements of traditional Zionist ideology, such as the creation of a “new Jewish person” who is physically strong and able to defend himself, and combined it with a religious and ultranationalistic ideology that turns both Israel and Jewishness into something completely different, like a mutation. Netanyahu gave the most extreme people unprecedented political power in his government. That, together with the October 7th catastrophe and the war that followed it, set Israel on a disastrous path. Those people want to change Israel to a nondemocratic theocracy, and indeed they are already using their powers to advance their program.

I always see myself in the lives of my protagonists.… At the same time, I try to keep some distance from them, which enables me to watch over them with irony and criticism.

ROS: This seems to be an especially precarious time for the Israeli Left, which is often accused of being disloyal to Judaism or “self-hating Jews” and so on. Right-wing zealots sometimes claim to be the country’s only authentic Jews. How do you see the relationship between the Israeli left and Judaism?

YS: Well, that is a big subject. Let me say this: I think that Israel’s liberals are much closer to the Jewish spirit and values than right-wing extremists, who call themselves religious but spread racism and hatred. Israel’s Left has very strong roots in Jewish history, tradition, and culture, and wants Israel to be an open and liberal society. This vision of Israel is changing every day now. We are carried away by strong waves of nationalism, portrayed as “real Judaism.”

ROS: In Victorious, the protagonist, Abigail, is a military psychologist and lieutenant colonel who relishes her work training combat troops, ensuring they are effective, unquestioning killers. She is a brilliant interpreter of the nightmarish dreams of soldiers and works to build their confidence and resilience before and after combat. She is gifted at forcing open the repressions and silences that might haunt them later, if left untreated. She sharply intuits “the traces of trauma between the lines.… The shadows of the people they’d killed were in the air, I could see them hovering over their shorn heads.” Abigail presides over harsh interrogation and captivity training exercises that brutalize male as well as female pilots who might fall into enemy hands. But she is also a single mother, deeply fearful about the fate of her young son. Given the constant presence of war and terror in everyday life, PTSD has always been a factor in the lives of so many Israelis. But in the aftermath of the vicious massacres and abductions of October 7th and now the escalating hostilities with Hezbollah in Lebanon, it often feels that the entire country is heavily traumatized. Do you or your Hebrew readers see Victorious in a new light, given how embattled the entire country seems today?

YS: Yes, this terrible war magnifies Abigail’s complicated mission. Israel has been absorbed by pain, bloodshed, and trauma for over a year now. That has had a huge effect on everyone. There are many new PTSD cases among soldiers and civilians. Abigail’s job is to treat those patients, but at the same time she is an expert at training young soldiers how to kill other human beings on the battlefield. This expertise becomes very personal when her son is recruited into the army. The role of Israeli parents, especially mothers, in educating their children to be good soldiers and risk their lives is a very sensitive issue.

ROS: To my mind, Abigail is the most compelling portrayal of an Israeli military mother since Ora in David Grossman’s To the End of the Land. Some of your other memorable works have featured strong, opinionated, and prickly Jewish mothers and have sometimes focused on their fraught relationships with their sons. How have female readers or critics in Israel responded to these complex portrayals?

YS: They raise all kinds of emotions in readers. I first wrote a female protagonist in Naomi’s Kindergarten, which was published in 2013 (and has not yet been translated into English). At first I hesitated to write from a woman’s point of view, but I simply had to in order to save the book. When she started talking to me in my head as I wrote, I knew I was doing the right thing. I don’t believe we are all-masculine or all-feminine; we are much more diverse and interesting. Abigail’s job is connected to war, which used to be considered a male business, but now in Israel we see that women have become much more involved in combat missions, as pilots, tank operators, etc. Still, many readers had a hard time coping with her specialty in the psychology of killing, which seemed to them inappropriate for a woman. But it is actually very plausible. Israeli mothers in general provide immense moral support when their children are recruited into the army, therefore enabling this war machine to move on.

ROS: Victorious grapples so brilliantly and provocatively with Israel’s aggressive codes of conduct, and I think for many readers it produces more questions than answers. Your examination of the toll of survival, militarism, and aggressive nationalism in the Jewish state is nuanced and disturbing. Did your own personal military experience influence this novel, or did you draw on the memories and experiences of other Israelis in portraying this painful reality?

YS: I served in the IDF for six years. I was an intelligence officer and had some combat training, but did not participate directly in combat. I know quite a lot of people who did and of course their stories inspired this book. Abigail also does not have personal combat experience herself, but through her work is very close to combat and has heard many combat stories. That is part of her complex connection to war and killing — she is an expert in this field and feels frustrated about not experiencing it firsthand.

ROS: I immigrated to Israel in 1975, served in the IDF, and was among the final groups of soldiers to serve in Sinai before it was returned to Egypt. Like many others, I experienced Sadat’s visit to the Knesset as a euphoric moment of transformation for the Middle East. So I do believe in the possibility of peace, that it can come at any time, as long as there is genuine leadership and a willingness to compromise. But I realize that after the atrocities of October 7th and so many months of the war between Israel and Hamas, many might find any mention of a future peace and coexistence too absurd to seriously contemplate. I read that when you won the Levi Eshkol Literary Award, you donated the prize money of forty thousand Israeli shekels to a grassroots organization of Palestinian and Israeli families who have lost relatives to the conflict. Given the pessimistic era we are in, do you think that even now such groups can effectively serve as a bridge for people struggling to work toward reconciliation? Do you have any hope for the future?

YS: We are locked in a deadly conflict in which Israelis and Palestinians are both being dehumanized. I am not willing to accept a future of eternal violence and hatred. It might be hard to imagine right now, but I believe that some time in the future, common sense will prevail, and people will find a fair political solution that will enable them to raise their children in peace. It will not be a love story, but it will be better. Meanwhile, we should encourage any little sign of good will — that is what organizations can achieve amid a sea of hatred and violence.

ROS: I was very moved by how the ghost of Prime Minister Rabin seems to haunt the end of this novel. Do you often think about him and his legacy? You also employ the Akedah (binding and near-sacrifice of Isaac) to devastating effect. Since the earliest days of the state, poets and writers have examined its repercussions on the Israeli psyche. In your novel, it figures in such a grotesque and traumatizing way. How long have you been thinking about this vital biblical trope and its role in Israeli culture?

YS: The assassination of the prime minister was a turning point in Israel’s history. I attended the rally in the central square of Tel Aviv when it happened, and immediately understood that it would change Israel forever. I will never forget that terrible night. It was the result of an orchestrated campaign of hatred, incited by the same groups who plan to build the temple and eliminate Israel’s democracy today. That is the root of the scene you mentioned in the book. The motive of the Akedah is part of our lives here. We face it every day with the sacrifices of young soldiers. I deal with that theme in Victorious as well as in The Third Temple. The danger arises when war and violence become an ideal nurtured by rabbis and politicians.

ROS: You studied law at Hebrew University, and I’ve read that you still practice law. Has the spare prose of court narratives been an influence on your distinctive voice as a literary writer? Have you always been able to write your novels with such economy, or do you find yourself having to prune your prose a great deal before you are satisfied?

YS: I do try to write in a lean and effective manner. I think my legal practice taught me how to write very complicated narratives in a clear and concise way. However, I am careful not to let my legal background affect my prose too much, because that might be a disaster. I think the most important influence on my writing is the marvelous style of the unknown writers of the Bible. They were able to tell the most dramatic stories in a few sentences, in which every word counted. They are a great inspiration to me.

ROS: You have written seven books to date, and the ones available in English have won awards and attracted a strong readership. Are there any plans to translate any of your other works into English, such as Naomi’s Kindergarten or The Investigation of Captain Erez?

YS: I hope, and anticipate, that all of them will eventually be published in English, which is of course very important to me. Literature does not have an expiration date, so I am sure this will happen.

Ranen Omer-Sherman is the JHFE Endowed Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Louisville, author of several books and editor of Amos Oz: The Legacy of a Writer in Israel and Beyond.