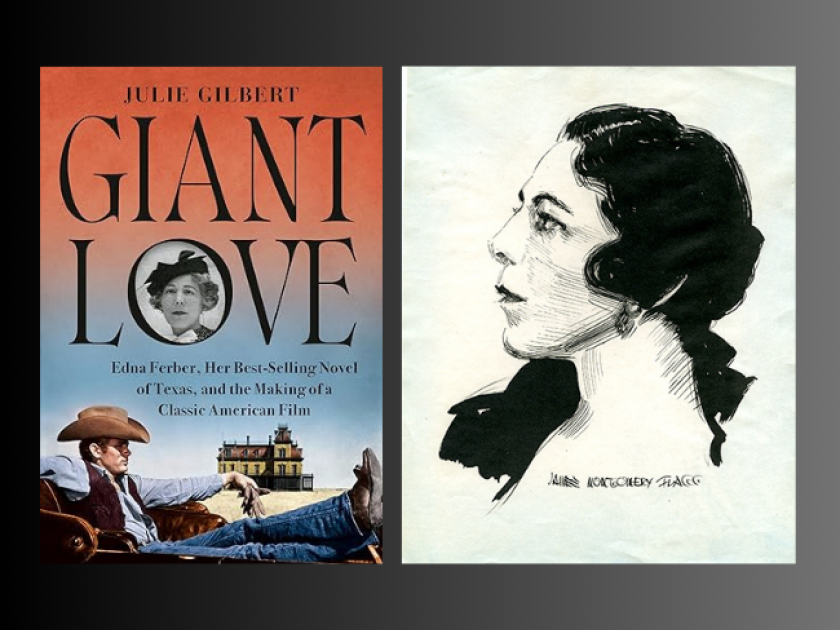

Portrait of Edna prior to her theatrical debut in The Royal Family at the Maplewood Playhouse in Maplewood, New Jersey, 1940

Credit: Ferber Family photo collection. Courtesy of Julie Gilbert.

Allow me to introduce myself: I am a professional writer, the great-niece of the Pulitzer Prize – winning writer Edna Ferber, and the trustee of her estate. My latest book, Giant Love, focuses on Ferber’s 1952 novel, Giant—how she came to write it, what happened when she did, and what happened when director George Stevens made it into a movie. My book is about other subjects, too: our family, Ferber’s personality, her work habits, her illustrious friends, and the irritations and intoxications of success.

My great-aunt was known as a great American writer of short stories, novels, and plays. Your parents and grandparents would have likely been avid readers of her novels So Big, Show Boat, Cimarron, Saratoga Trunk, Giant, and Ice Palace—all of which were made into motion pictures. They also might have seen the plays that she collaborated on with George S. Kaufman, like The Royal Family, Dinner at Eight, and Stage Door. In 1925, she was the first American Jewish woman writer to win the Pulitzer Prize, for her novel So Big.

She was born in 1885 and died in 1968. She was a champion of women’s rights, writers’ rights, and the fight against antisemitism. She was a warrior woman against injustice of all kinds.

I would like to reintroduce the reading public to Edna Ferber by relating two small anecdotes.

Ferber was forced to confront antisemitism as a small girl in the deeply midwestern city of Ottumwa in the state of Iowa. Her parents owned a dry-goods store, which they boldly named MY STORE. Jacob Ferber, a Hungarian immigrant, and his wife, Julia, began to create their own diaspora, moving through the Midwest from Chicago to Ottumwa, and then later on to Appleton, Wisconsin, before going back briefly to Chicago and resettling in Appleton.

When they had moved the business to Ottumwa, plucky Edna became deeply subdued by a series of incidents. No one in the family owned a motor car, so they hiked everywhere they needed to go. Small Edna and her older sister, Fannie, walked over two miles to school and back every day. Because they were in different grades with different starting times, they would often walk alone.

Sisters: baby Edna (left) and Fannie, 1885

Credit: Ferber Family photo collection. Courtesy of Julie Gilbert.

Edna’s most direct route would take her past a picket fence abutting a pasture. On top of the fence would sit a little girl with golden curls, who would systematically screech at Edna: “SHEENY, SHEENY, SHEENY!” Edna would walk past silently, head held high, enduring this torture for quite some time. It amazed her that no matter the weather, the little demon would always manage to be there. It became almost like a contest to see if Edna would ever crack, or if the perpetrator would ever stop. Neither did.

That’s the story. The family moved on to live very happily in Appleton, Wisconsin, where the store flourished. Edna was prominent and popular in all her school’s activities, and she eventually became a leader in high school. She was apt in her studies, starred in school plays, and served as editor of her yearbook.

Promising in every way, she went on to attend college for two years, after which she worked on the Appleton newspaper. She then moved to Milwaukee as a reporter and journalist on the local newspaper.

The Ferbers’ family business, circa 1980

Credit: Ferber Family photo collection. Courtesy of Julie Gilbert.

Misfortune struck when her father began the descent into blindness, leading Edna to move back to Appleton to help the family out. Soon, her father died, and she pitched in all the more, writing in her precious spare time. The novel that she was working on turned out to be her first published novel, Dawn O’Hara, the Girl Who Laughed. After that, she wrote a slew of short stories, which catapulted her into fame — first local and then national.

And that could have been that. The little flaxen-haired menace from atop the fence in Ottumwa seemed to belong to the past. However, the best stories always have a good denouement.

Cut to the time after Ferber was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for her novel, when she was enjoying her Show Boat glory. She was asked to speak before a group of female fans in New York City. Always an elegant, articulate, and often amusing speaker, Ferber wowed the crowd. They had brought copies of her various books to sign, which she graciously did.

Edna at age forty-three, having had her nose bobbed, circa 1929

Credit: Ferber Family photo collection. Courtesy of Julie Gilbert.

Suddenly, a frazzled-looking middle-aged woman elbowed through the group toward her. Upon reaching her target, she started to exclaim loudly that Ferber was her favorite author in all the world, and that they had known each other as girls in Ottumwa way back when.

“Oh, yes,” said a velvet-voiced Ferber. “I certainly do remember you. You were the little antisemite who used to make my life a living hell.”

Then there was the time when, at a luncheon given in her honor, a woman posed the always impertinent-cum-threatening question: “Miss Ferber, are you Jewish?” Ferber rose up to her full 5’1 stature, and using her iciest tone, replied, “Only on my mother and father’s side.”

Through the twenties, thirties, and forties, Edna Ferber was a literary American heroine. Her short stories featured middle-class Jewish American women juggling families and burgeoning careers. Her novels focused on American heroines venturing into the workplace, and how that affected the supposed harmony of the sexes.

Ferber was more a cultural Jew than a practicing one. Following the rise of Adolf Hitler and World War II, she wrote her own kind of bible. It was called A Peculiar Treasure, published by Doubleday, Doran & Co. in 1938. It was dedicated to my mother and aunt: “To Janet Fox and Mina Fox with the hope that my reason for having written this book may soon seem an anachronism.”

She ends the book as if addressing that little antisemite on the fence:

It is a world I do not recognize. I am like a woman disappointed in love — in her love of the human race … All my life I have lived, walked, talked, worked as I wished. I should refuse to live in a world in which I could no longer say this.…

It has been my privilege then, to have been a human being on this planet Earth; and to have been an American, a writer, a Jew. A lovely life I have found it, and thank you, Sir.

So come Revolution! Come Hitler! Come Death! Even though you win — you lose.

My new book, Giant Love, is all about Ferber’s novel Giant and the classic American film of the same title. But it is also about prejudice and vilification — this time in the Texan treatment of the Mexican American. Edna Ferber proved throughout her career that whatever is old is new again.

Edna, age thirty or thirty-one, a successful midwestern writer, circa 1916

Credit: Ferber Family photo collection. Courtesy of Julie Gilbert.

Julie Gilbert was born in New York City and was educated at Boston University. She is the author of four books, among them a biography of her great aunt, Edna Ferber, Edna Ferber and Her Circle and Opposite Attraction: The Lives of Erich Maria Remarque and Paulette Goddard, Gilbert is a member of The Dramatists Guild; The Writers Guild of America; East; The Authors Guild; Actors’ Equity; and League of Professional Theater Women. She has taught Creative Writing at New York University’s School of Continuing Education and currently heads The Writers Academy at The Kravis Center for the Performing Arts in West Palm Beach, Florida, where she lives part time, as well as in New York City.