Someone recently asked me why I write in Yiddish. This is a question I receive with some regularity. Of course, it’s something that’s asked of those who engage in any prolonged way with the language. When I was a student in the Uriel Weinreich Program in Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, my Yiddish grammar teacher, the eminent linguist Mordkhe Schaecter, said something along the lines of that he never asked a student why s/he was studying Yiddish. Would a student of French be asked why s/he were studying French? The question implies that there is a need to justify the study of this language, the lingua franca for East European Jews for centuries and a cultural repository for so much that is Jewish, as evidenced by the language’s very name, which, after all, means “Jewish.” Aren’t these characteristics alone sufficient reason? I wondered if Dr. Schaechter wanted to turn the question on its head: Why don’t more people study Yiddish?

The question has added poignancy of late due to the publication of my most recent book, A moyz tsvishn vakldike volkn-kraters: geklibene Yidishe lider/A Mouse Among Tottering Skyscrapers: Selected Yiddish Poems. As its subtitle suggests, the book is entirely in Yiddish. In fact, it is my first one to be only in Yiddish. It includes the Yiddish poems from my previous books as well as uncollected others. When I told a poet friend about this, she asked, “Who will read it?” I assured her there are indeed Yiddish readers left. I wasn’t satisfied with my response to that question. A more appropriate one might have been that the question of readership is separate from the question of writing. But neither was I satisfied with the answer I gave in real time to the question raised at the outset of this essay.

I write in Yiddish because I refuse to be denied my cultural heritage. Yiddish was a crucial element in the ultra-Orthodox yeshiva world in which I was raised. Yiddish words and expressions peppered speech. The teachers and the officials of the yeshiva spoke Yiddish. My parents spoke Yiddish. I speak Yiddish today with my father. And yet growing up, I never read or even heard of the works of the canonical Yiddish troika of Mendele Mokher Sefarim, Isaac Leib Peretz, and Sholem Aleichem, let alone the works of more recent Yiddish masters such as David Bergelson, Jacob Glatstein, Itzik Manger, or Blume Lempel, an innovative writer whose work Ellen Cassedy and I spent many years translating.

When I read Yiddish literature today, I’m immersing myself in a world that’s familiar and also alien. That world is familiar because of the religious life cycle that figures prominently in many Yiddish texts, and alien because of how far we are from the world not only of the East European shtetlakh but also of cities such as Łodz, Warsaw, and Vilnius. And it’s distant because I have no memories of studying this literature in my youth the way someone raised in a secular Yiddishist environment, who attended a Workmen’s Circle school or a Yiddish school, would have.

When I write in Yiddish, I’m placing my own small flag, however tattered, however imperfect, in the realm of new Yiddish literature. I’m staking a claim for Yiddish as a current, dynamic, ever-evolving language for literary creation and my own tiny tent within it. In Yiddish, I can exist in the beys-medresh disputing Talmudic minutiae or studying ethical texts and at rallies and demonstrations fighting for justice. I can be in the butcher shop and the grocery store, perusing Paskesz candy offerings and in the salons sampling the latest literary releases. I can be singing Askinu sudose at the third Sabbath meal and “Harbstlid” by the Yiddish poet Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman. I can … Well, you get the idea. All of that and more — past, present, and future — is simultaneously available to me.

And when I write in Yiddish, I don’t have to think about a glossary or about how to make the religious and other terms and expressions in my work accessible to readers. Readers of Yiddish will know the meaning of words like Shvues or havdole or shadkhonim. Nor do I have to think about the transliteration system I am going to use and whether I should transliterate words Yiddishly or Hebraically and what transliteration system I should use. My readers won’t need that guidance.

And yet, Yiddish is not my first language. I have to look many English words up in the dictionary — not only to determine their parallels in Yiddish, but also their genders. I have to think about the case of a particular linguistic context. I have to consider whether what I’ve written works idiomatically in Yiddish. I have to find someone to proofread. That person has to have both a profound knowledge of Yiddish and a proofreader’s sensibility. Once a manuscript is ready, I have to find a publisher willing to work with Hebrew fonts. This person usually doesn’t know Hebrew or Yiddish, which causes numerous design and layout challenges. I am extremely fortunate that I have found individuals who sustained my Yiddish work in so many ways at each stage of the creative process.

I am therefore constantly reminded of the audacity needed to create literary work in a language that is not one’s first. Some might call it folly. But this tension between comfort and struggle, between familiarity and distance, is ever present. Sometimes it feels like outright paradox: that which sets me free also weighs me down. The very tool used to explore my own heritage limits the essential freedom needed by the writer. Simply put, I can’t let Yiddish go.

Even if I don’t ask myself “Why do I write in Yiddish?” the question of “Will I continue?” is ever present. My commitment to writing in Yiddish is never a given for me; it requires constant renewal. The added layer of work entailed requires a self-interrogation: Will this project also entail Yiddish? To this point, the answer has been “yes.”

Of course, writers want readers. We want our work to be considered, absorbed, and savored. We want it to bring understanding, pleasure, or beauty into the cosmos of readers. But we also write for specific reasons, some of which have to do with our own histories and backgrounds, while others have to do with specific contingencies of the moment. Yiddish literature is replete with examples of those who didn’t start writing in Yiddish or who wrote in multiple languages. Arguably the national poet of Israel, Hayyim Nahman Bialik wrote Yiddish poems. Rachel H. Korn first published in Polish. Vladimir Medem, the Bundist theoretician, wrote in Russian first. And there were so many others. These writers had a range of approaches vis-a-vis multi-linguality. Some turned to Yiddish from other languages. Some turned away from Yiddish. Others wrote in multiple languages. Of course, there was a considerably more vibrant Yiddish context in their days, but my point is that my path is hardly a new one. And the examples of multilingual writers outside of Yiddish literature are vast. Think of Samuel Beckett, Joseph Conrad, Vladimir Nabokov, to name but a few.

My work takes place in the context of ongoing Yiddish literary activity around the world today. Contemporary Yiddish writers include Velvl Chernin and Michael Felsenbaum, the Israel-based publishers of my most recent book and central forces behind the Library of Contemporary Yiddish literature; poets of the Yugntruf Yiddish writing circle in New York, and many others, from Melbourne to Los Angeles and Indiana. Many of these writers purposely create in several languages. I take heart from the multilingual example of these forebears and contemporaries as well as sustenance from their enduring creativity. I find meaning in moving between languages, in communicating with readers through these different means. Perhaps Dr. Schaechter would be pleased.

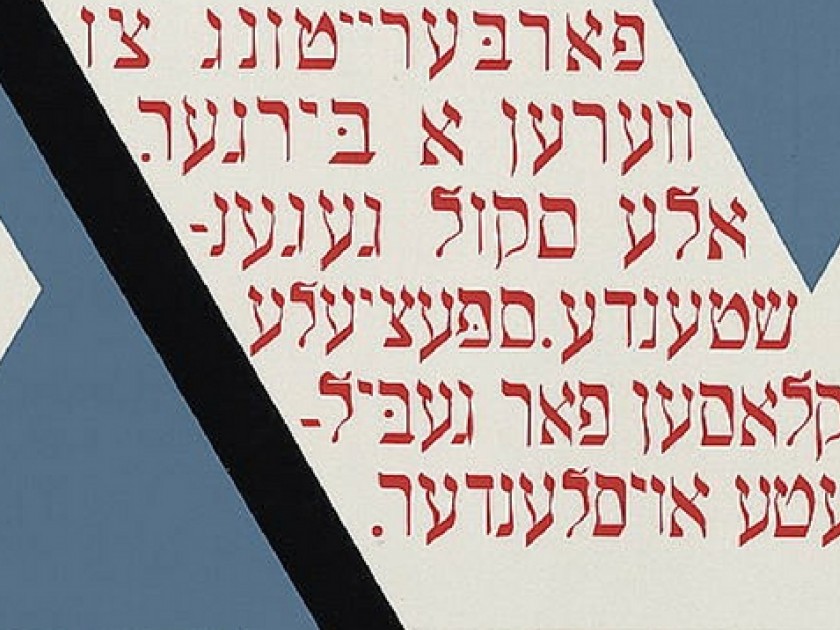

Image via Library of Congress

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub is the author of six books of poetry: The Education of a Daffodil: Prose Poems/Di bildung fun a geln nartsis: prozelider, A moyz tsvishn vakldike volkn-kratsers: geklibene Yidishe lider/A Mouse Among Tottering Skyscrapers: Selected Yiddish Poems, Prayers of a Heretic/Tfiles fun an apikoyres, Uncle Feygele, What Stillness Illuminated/Vos shtilkayt hot baloykhtn, and The Insatiable Psalm. Tsugreytndik zikh tsu tantsn: naye Yidishe lider/Preparing to Dance: New Yiddish songs, a CD of nine of his Yiddish poems set to music, was released in 2014. He was honored by the Museum of Jewish Heritage as one of New York’s best emerging Jewish artists and has been nominated four times for a Pushcart Prize and twice for a Best of the Net award.