Illustration by Marc Chagall, from The Magicians by I.L. Peretz in 1917, image from the National Library of Russia

For Jews all over the world, Passover is the festival of freedom. Specific rituals and traditional foods, as well as broader interpretations of liberation from enslavement are all parts of the eight-day observance. Children’s books about the holiday reflect these different elements of the celebration, from the history of the Exodus from Egypt, to tales of family relationships reflected in Passover preparations and the elaborate seder meal. Two children’s picture books remind readers of the holiday’s essential core, stripping away many of the external details to focus on enduring values such as faith and courage in the face of unimaginable obstacles.

In The Magician’s Visit: A Passover Tale (Viking Penguin, 1993), award-winning author Barbara Diamond Goldin retells I. L. Peretz’s 1904 Yiddish short story “The Magician,“ about a poor Jewish couple unable to afford even the basic necessities for their seder. When the prophet Elijah provides all they need, they are fearful and confused. With haunting watercolor sketches by Robert Andrew Parker, the book’s mythical archetypes of precarious shtetl life become real for young children, as the husband and wife from Peretz’s story accept their plight with humility and are rewarded for their faith. (Uri Shulevitz also adapted and illustrated the same story in 1973, with small, intense black-and-white drawings.)

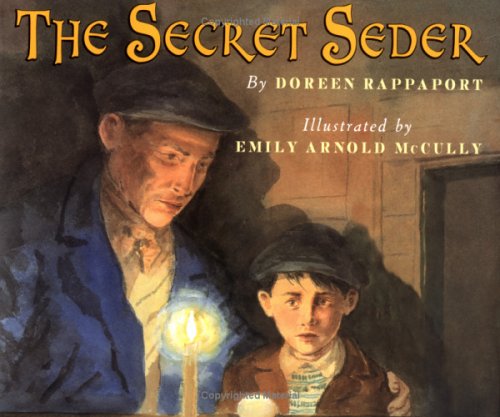

The Secret Seder (Hyperion Books for Children), written by acclaimed author Doreen Rappaport and illustrated by Caldecott Award winner Emily Arnold McCully, also recalls a Passover meal diminished by loss. In World War II France, a Jewish family is forced to choose between risking their lives or fulfilling their religious obligations. Although Elijah does not literally come to their rescue, their community invokes the prophet’s presence and defies the Nazis’ attack on their lives and traditions. Both books offer a view of redemption, providing a sense of hope without minimizing the harsh circumstances testing Jewish belief.

Both books offer a view of redemption, providing a sense of hope without minimizing the harsh circumstances testing Jewish belief.

The Magician’s Visit has minimal character development and little dramatic tension. As Goldin explains in her afterword, the prophet Elijah plays a major role, his powerful symbolism inhabiting many other Jewish customs. Participants in the sederopen the door and invite him in, and he also presides over a baby’s bris and is called upon to welcome a new week at the conclusion of the Sabbath. The prophet Malachi, in the eponymous Biblical book , announces that the coming of the Messiah will be preceded by the return of Elijah himself; in times of fear, this promise has assumed even greater importance. In Goldin’s narrative, the inhabitants of an unnamed small town in eastern Europe are getting ready for Passover, the holiday requiring more preparation than any other in the Jewish calendar. The book’s first sentence casually mentions that “a magician came to town,” suggesting an occurrence no more notable than any other. Indeed, this magician at first seems to be just one more poor Jew. His magic involves ordinary objects: he transforms rags into golden ribbons, and pulls turkeys out of his boots. Hayim-Jonah and Rivkah-Bailah are struggling to survive; their predicament is unremarkable.

Peretz, in Goldin’s retelling, gives almost no information about his characters’ plight, aside from the fact that Hayim-Jonah, a lumberman, has had “misfortunes.” The winter had been severe enough that they would not, proverbially, “wish (it) on even their worst enemy.” The couple’s childlessness goes unmentioned, yet it adds a poignant tone to their isolation. Hayim-Jonah is convinced that God will provide what they need for Passover. As Jewish law demands, they continue to give charity even while they have barely enough to survive. When they open the door to a stranger on the eve of the holiday, they apologize to him for their inadequacies as hosts. In the lowest emotional point for this deeply religious man, Hayim-Jonah responds to the visitor, “I’m sorry…but we have no Seder.” Ironically, although he had previously reprimanded his more practical wife for her sadness, he now shares her despair. At this point in the story, young children may experience the couple’s disappointment, although adult readers will recognize the magician’s true identity.

In 1923, Marc Chagall illustrated an edition of Peretz’s story in the original Yiddish. Although Parker’s artwork for the book is far more somber in tone, with dark, muted colors dominating, his picture of the magician as Elijah recalls Chagall’s mystical joy. His face emerges from the shadows bathed in white, with two white circles in the background suggesting wings or haloes. He holds out two gold candlesticks with bright orange flames. Yet even when he causes a tablecloth to drop from the ceiling and matzah, wine, and a shankbone to materialize from nowhere, the man and his wife are not convinced and decide to consult their rabbi. Any child who has examined Elijah’s cup at his or her family seder to see if some wine has been consumed will be waiting for the rabbi’s decision on the difference between magic and miracles. His answer is helpfully specific: magic is a “deception,” but if the matzah crumbles, the visitor’s gifts are real.

Any child who has examined Elijah’s cup at his or her family seder to see if some wine has been consumed will be waiting for the rabbi’s decision on the difference between magic and miracles.

In The Secret Seder, no such feeling of assurance is available to the young Jewish boy and his parents attempting to pass as Christians in Nazi-occupied France. The boy lives in terror of the “black boot men” who take Jews away; his own grandparents have disappeared. Yet he secretly practices reciting the Four Questions with his mother, and when the first night of Passover arrives, his father leads him to the forest to share a secret sederwith a group of terrified but resistant Jewish men. His father reasons over his mother’s fears that “Just being a Jew is dangerous.” Here the danger is not only poverty, but death. The men are reciting the evening prayers together before the seder begins, each with a ragged coat over his head in place of a tallis. Some of the men are crying. The boy vividly remembers his grandparents’ bountiful table of the previous year; here there is only one candle, wine, and one piece of matzah. The sorrow on the men’s pale faces and the drab colors of brown wood and clothing are relieved by the bright light of the candle. No magical figure enters to reward their refusal to accept defeat.

Unlike Hayim-Jonah’s and Rivkah-Bailah’s peaceful seder, this one is marked by contention. An old man, lacking a full Haggadah, reads from a ragged sheet of paper, which looks like a newspaper bringing the tragic events of the day to its readers. A heated argument, not unlike Talmudic disputes, ensues when the men disagree about the different periods of adversity in Jewish history. Their anger and fear merge in one moment when a woodcutter who had been standing guard outside suddenly opens the door. Only his shoe and a narrow part of his leg are visible, making his identity unclear. McCully shows all faces turned toward the stranger, some men rising from their seats in expectation of being seized by the enemy. At the same time, the scene evokes the entrance of Elijah as a promise of deliverance. Later, when the time arrives for opening the door for the prophet, only “a cold blast of wind” enters. Again, the group’s expectation is implicit: “No one speaks as we listen to the wind.” Elijah does not enter, but one of the men declares the traditional, “Next year, in Yerushalayim,” followed by “we shall come together for a great feast.”

The reader knows what the man at the seder does not. Many Jews will die, but those who survive will return to observe Passover, some with renewed hope. Not long after the War, the State of Israel will be founded, viewed as the fulfillment of God’s promise by some, and by others as a secular fulfillment of messianic hopes. The wandering magician who visits Hayim-Jonah and Rivka-Bailah is rooted in shtetl life, familiar with their humble prayers and hopes for material betterment. When the rabbi assures them that their faith has not allowed them to be deluded by magic, their seder has been redeemed. They will wait patiently and without a sense of urgency for Elijah’s later arrival before the ultimate redemption. The Jews of The Secret Seder cannot rely on unquestioning faith, although their faith has not disappeared. Their own obstinate bravery has redeemed their Passover celebration, filling the silence when Elijah fails to arrive. Each book offers children a different perspective on Jewish resilience as they open the door.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.