Images courtesy of the publisher

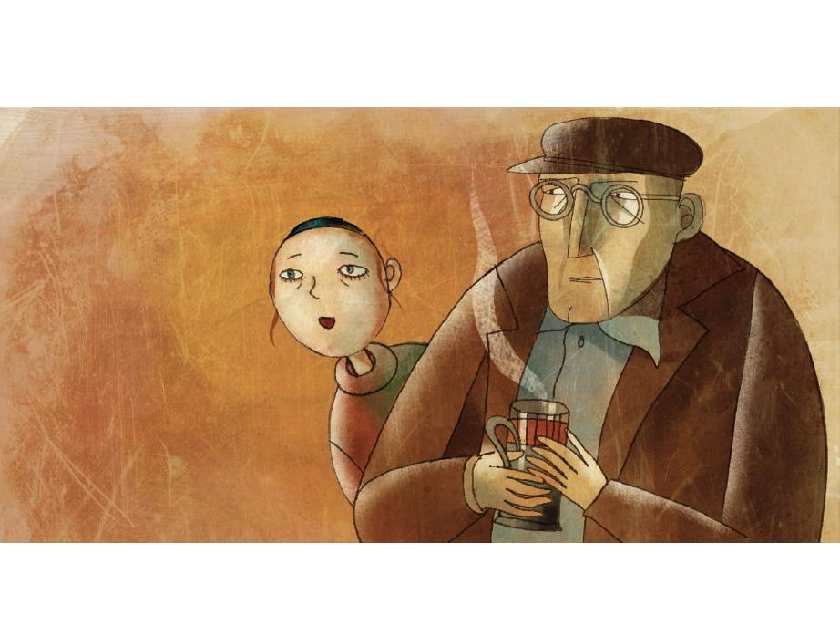

In 1965, an American rabbi travels to the Soviet Union to investigate reports of persecution of the Jewish community. Moscow welcomes him and the other American rabbis in his group as guests, but keeps them on a strict schedule. One afternoon, the rabbi slips away. With only an old address and almost no knowledge of the Russian language, he embarks on a secret journey to a part of Moscow where he discovers a little boy, Zev, who has never left the small apartment where he was born, and his parents who desperately want to protect him from Soviet-enforced assimilation.

Every time I re-read A Visit to Moscow, I find myself asking the same question.

Near the end of the book, after the rabbi goes back to his hotel in Moscow, Zev remembers the people and setting of the story in the previous pages. He remembers that the man at the table is the rabbi who visited him as a child in the Soviet Union, that he and his parents left the Soviet Union and went to Israel, that he eventually married and had his own children.

Zev also remembers the moment he died. And on the last page, he sees Jerusalem.

That is when I ask the question: Is it the earthly Jerusalem or the heavenly Jerusalem that Zev sees?

When I first heard the story that would become A Visit to Moscow from Rabbi Rafael Grossman, the basis of the fictional rabbi, I asked him endless questions about the real Zev and his family. I wanted to understand how the little boy would view the world. Would he be angry? Would he be afraid? Would he be bitter?

Zev had told Rabbi Grossman that when his mother was sleeping, he would turn the shade a little to see what was outside. Zev knew that in the winter it snowed. He knew there was rain. He knew when it was warm and when it was cold. As he looked out the window, he wondered about the world. He thought it was made up of mean people because he couldn’t go out and play, but — Rabbi Grossman emphasized — Zev never thought the world was ugly. He wanted to know more about it.

As soon as Rabbi Grossman arranged for their visas, Zev and his family flew from Rostov to Moscow to Europe to Israel. Zev thought the car that took them to the airport was an incredible thing and the airplane totally fascinated him. He talked about it at his bar mitzvah. He said he went up to Hashem and came down.

As he looked out the window, he wondered about the world.

Rabbi Grossman said that when he visited the family in Israel, Zev ran around showing him things: his school books, his tzitzit, his kippah. Zev was excited and full of life, introducing his pals to the Rabbi, shouting, singing — not at all restricted. He seemed to love everything in life.

I heard Rabbi Grossman tell the story of Zev and his family many times, and always when he told it, the Rabbi himself was excited and full of life. I think he and Zev were alike in many ways and that was why Rabbi Grossman never stopped telling the story. They both loved this world.

Rabbi Grossman was at Zev’s bar mitzvah in Israel. As part of his speech, Zev said, “I can’t believe what my parents went through so that I could be a Jewish, religious child.” Someone asked him, “Do you resent them? Are you angry at them?”

“Oh, no,” he said.

Rabbi Grossman said Zev was extremely happy in Israel. His life was filled with learning the language, making friends, and playing sports. He traveled on buses and went to every part of Israel; later, he went to a hesder yeshiva and received a degree in mechanical engineering. He married and had children. And through it all Zev had a very strong, loving relationship with his parents. Zev talked about the world as a beautiful place. He talked about Lebanon and said the mountains were extraordinary.

Lebanon, where as a young man he stepped on a land mine while on reserve duty and was killed.

That view of the world as an extraordinary place sustained Zev, whether in the one room in Moscow where he could only peek out the window or in the openness of the land and cities of Israel. I think for him, being alive on this earth was like being in heaven.

So, is it the earthly Jerusalem or the heavenly Jerusalem that Zev sees on the last page of A Visit to Moscow?

I’m sure Rabbi Grossman would know. I hope the reader will, too.

A Visit to Moscow, adapted by Anna Olswanger from a story told by Rabbi Rafael Grossman and illustrated by Yevgenia Nayberg, is out May 24, 2022.

Anna Olswanger first began interviewing Rabbi Rafael Grossman and writing down his stories in the early 1980s. She is the author of the middle grade novel Greenhorn, based on an incident in Rabbi Grossman’s childhood and set against the backdrop of the Holocaust. She is also the author of Shlemiel Crooks, a Sydney Taylor Honor Book and PJ Library Book, which she wrote after discovering a 1919 Yiddish newspaper article about the attempted robbery of her great-grandparents’ kosher liquor store in St. Louis.

Anna lives in New Jersey with her husband. She is a literary agent and represents a number of award-winning authors and illustrators. Visit her at www.olswanger.com.