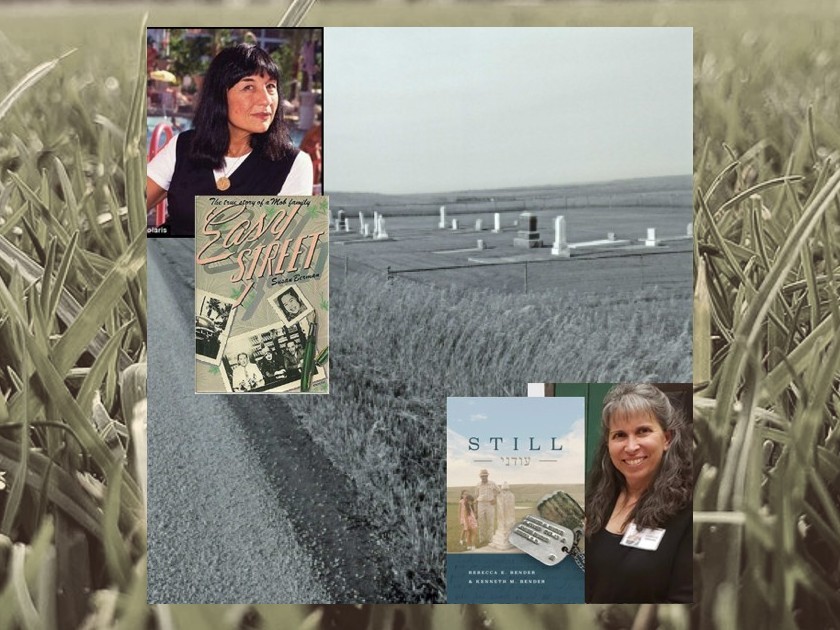

Susan Berman, upper left, and Rebecca E. Bender, lower right (Author photos by Gerardo Somoza and Michael Miller respectively)

North Dakota Jewish Homesteaders Cemetery where their ancestors were buried (Photo by Rebecca E. Bender)

About thirty years ago, while sharing a corned beef on caraway rye sandwich at her retirement home in LA, my ninety-six-year-old great-Aunt Nola leaned in close to me. In a mystical voice she said, “I was born on August 18th. You were born on May 18th. The Hebrew letters for eighteen spell ‘chai’ (life). You have the power of eighteen, just like me. You will achieve unexpected things when you’re older.”

At the time, I was a securities litigator and assumed I would continue doing this the rest of my professional career.

But after eighteen years as an attorney, I put my law license on hold to deal with family health issues. So began my time in a variety of jobs, including teaching children, from a Hutterite Colony in North Dakota, to a junior high class in South Phoenix.

Twenty-four years after the conversation with my aunt, my son and I were paying our respects at the remote Ashley, North Dakota, Jewish Homesteaders Cemetery, where my great-grandfather Kiva Bender is buried. My son’s questions to me about this Jewish immigrant farming community lit a spark. I became determined to preserve the history and legacies of the Ashley, North Dakota, Jewish homesteaders.

I soon found myself researching in the musty archives at the North Dakota Historical Society and the Upper Midwest Jewish Historical Society. Though not a trained historian or writer, I found inspiring stories that I felt compelled to share.

My great-grandparents had traveled from the Black Sea area of the Russian Pale of Settlement to Antwerp, Belgium, where they boarded the Red Star Line in steerage for America – just like Irving Berlin, Golda Meir, and countless others. The impetus for my family’s move across the ocean was the murder of two of their sons in the 1905 Odessa pogroms.

Over 400 Russian and Romanian Jewish homesteaders escaped persecution and settled on around eighty-five farms amid the swaying grasses in McIntosh County, North Dakota, beginning in 1905. From the 1880s through the 1930s, 1200 Jewish farmers lived on over 250 homesteads in North Dakota – the fourth largest number of Jewish homesteaders in any state, behind only New Jersey, Connecticut, and New York.

My son’s questions to me about this Jewish immigrant farming community lit a spark. I became determined to preserve the history and legacies of the Ashley, North Dakota, Jewish homesteaders.

Despite having no farming experience (Jews were not allowed to own land to farm at the time in Russia), intense climatic challenges (prairie fires, tornados, blizzards), and rocky land (they had to clear each acre with a pickaxe, a crowbar, a horse, and a stone boat), my ancestors became successful farmers on North Dakota’s plains. They prospered enough to purchase their 160 acres of land outright for $200, (the equivalent of $6000 today) prior to the prescribed five-year waiting period under the Homestead Act. Along with their neighbors, they proved that “Jews could be good farmers, if given the chance.”

Additionally, I learned that my great-grandfather Kiva Bender was a lay leader of the early Ashley Jewish community. Though he arrived in America in 1906, with no knowledge of English, he formed the first Ashley Jewish Congregation shortly thereafter (registering it in the American Jewish Year Book, published by the Jewish Publication Society in Philadelphia) and established one of the first two Jewish farming cooperatives in the United States around 1908. He presided at Jewish weddings, led services in the Bender barn, and put ads in east coast publications, urging Jews to come to “the Great Northwest.” When he died in 1913, the front-page headline in the German and English Ashley Tribune was, “Well-Known Jew Dies.”

Though life was seldom easy for these new farmers, the Jewish homesteaders were in the land of the free. They could go listen to recordings of the Jewish Russian Orchestra on a neighbor’s Victrola phonograph while savoring hot tea with verenya (jam). They could gather with their community and pray without fear as a congregation on holidays. And the Jewish weddings under the infinite prairie sky, with fiddlers and wash tub drums, were legendary.

It was in the North Dakota archives when researching that I first saw Susan Berman’s name. She had written a book in the early 1980s, Easy Street (Dial Press 1981), after learning more about her Jewish homesteading ancestors and following the death of her parents. Just like me, I thought. The marker of her uncle, found in the cemetery, was the only evidence that her family had ever lived there. Just like me, I thought again.

Because of bad luck – a burned down sod house due to her grandfather forgetting to close the hearth after putting in cow chips and hay for fuel – Berman’s family left Ashley. Susan’s father, known as David, then started on a path in Sioux City, Iowa, that would eventually lead to his being one of the founders of Las Vegas (making Las Vegas “bloom,” according to the rabbi at his funeral). He started the first synagogue in Las Vegas, was a partner in the Flamingo and Riviera Hotels, and became one of the most powerful gangsters in America.

Though these latter facts resulted in Susan’s more recent family history being entirely different from mine, I felt a connection and wanted to share our ancestors’ stories. I had seen a wedding license for my great-aunt Sarah which included Susan’s grandfather’s name as a witness. I had also seen evidence of her grandfather’s involvement as an officer in the Jewish farming association started by my great-grandfather.

I looked forward to contacting Susan and went online. I first saw her photo. Susan had long dark hair and bangs, like me. She was born in Minnesota, I discovered, again like me. As I continued reading, I was saddened to see that Susan had been murdered in 2000, at age fifty-five. I then noticed that Susan and I were both born on May 18th.

_____

One of two boulders with plaques at the Ashley, North Dakota Jewish Homesteaders Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the author

Against the odds, and feeling an unexplainable force pushing me forward, I succeeded in getting the Ashley Jewish Homesteaders Cemetery listed on the National Historic Register by the United States Department of the Interior. I then conducted fundraising to have educational plaques on two-ton boulders installed at the site and with the help of the two other Cemetery Association Board members and family members, organized a rededication, which brought over 100 people – Jews and non-Jews – from six states.

But I felt the work I was supposed to do was not quite complete. At age sixty, I combined my late dad’s vivid recollections with my research into my first book—Still (North Dakota State University Press 2019). It describes five generations of my family and the communities of which they were a part, overcoming challenges and trying to lead good lives with tradition, kindness, and faith.

My aunt Nola was a wise woman. With a few words, she convinced me I had a special power. That belief cleared an unexpected path for me, one I might not otherwise have had the courage to take.

_____

Also against the odds, in September 2021, Susan Berman’s murderer was found guilty, twenty-one years after she was killed, and was indicted for killing his wife, almost forty years earlier. Susan was a talented writer with an eye for detail. But what connects her to me forever is that she, too, was a daughter of the Ashley Jewish Homesteading Colony. She was interested enough in her roots to travel from the land of palm trees to icy North Dakota.

Sadly, Susan’s life was taken before she was lucky enough to experience her second act – her power of eighteen on earth. I like to think that Susan, the author, has now finished writing the epilogue to her earthly story.

Rebecca E. Bender, who wrote this piece, and her father Kenneth M. Bender are coauthors of Still (NDSU Press 2019), a biography/memoir of five generations of their Jewish family on three continents. Still is the 2019 Independent Press Award Winner (Judaism category) and the 2020 Midwest Book Award Gold Medal Winner (Religion/Philosophy category). Rebecca’s prose and poetry have appeared, inter alia, in The Journal of The American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, North Dakota Quarterly, The Jewish Veteran, the Forward, Australia’s Jewish Women of Words, the StarTribune, Mandala, The Northwest Blade, The San Diego Jewish World, and previously in Paper Brigade Daily (Jewish Book Council). She has recently completed two other projects: a Still screenplay adaptation and a children’s storybook, based upon fact, about a young Jewish girl living on the prairie with her homesteading parents in the early 1900s, with each story focusing on a core value of Judaism. Still, with a second printing out in paperback in March, is available through NDSUPress.org, Amazon.com, or can be ordered through any bookstore.