The Letter of Aristeas is probably the most optimistic Jewish document ever produced in the ancient world. The novella imagines a glorious collaboration between the Hellenistic Greeks of Egypt and Jewish authorities in Jerusalem, who enthusiastically embark on a project to provide Egyptian Jews with a Greek Torah. This charming story, which celebrates the Jews of Egypt and the warm affection lavished upon them by their Judean kin, has been interpreted as evidence that Jews thrived outside Judea in the Hellenistic era. As with any ancient document, however, there’s more than meets the eye. Did Jews in the Land of Israel really support a translation project that would enable Jews in Egypt to read their scriptures in Greek?

The answer is probably not. In the Hellenistic era, Jews living in Israel were likely deeply concerned by such projects. They were aware that there were more Jews living outside the Land of Israel than within it, and that most Jews abroad were not turning to Judean Jews for spiritual guidance or collaboration. Many of these Jews lived in Egypt, the very place where Israelite settlement is proscribed in the Book of Deuteronomy. Egyptian Jews practiced their ancestral laws, sent money to the Jerusalem Temple, and some even made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. They also built synagogues, where they gathered to read and interpret their scriptures.

All of this posed a major conundrum for Judean Jews. How were they to understand the fact that the Jews’ prophets had called on the people to return to their homeland at their earliest opportunity, while observant Jews — in Egypt, of all places — nevertheless seemed to be thriving?

This question lies at the heart of letters that Jews in Jerusalem wrote to Jewish leaders in Egypt in the second century BCE. On the surface, these letters implored Egyptian Jews to observe an annual holiday commemorating the Judeans’ extraordinary victory over the Syrian Greeks, a holiday that would later become known as Chanukah. Underneath this benign request, however, lay a deeper worry that Egyptian Jews were drifting away from their Judean counterparts, and growing increasingly disconnected from Judean affairs.

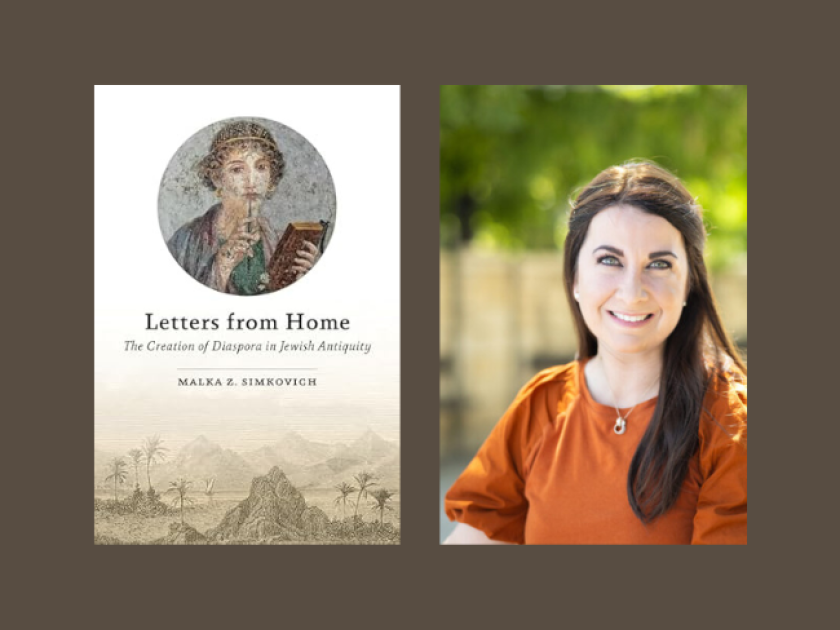

My recent book, Letters From Home: The Creation of Diaspora in Jewish Antiquity, explores these and other Judean documents, alongside Jewish texts produced in Egypt, and considers how Jews within and without the Land of Israel thought about one another — and sometimes misunderstood one another. My analysis shows that, whereas Jews outside the Land of Israel argued for the legitimacy of their Jewish practice and believed that the Babylonian exile had ended centuries earlier, Jews living in the Land of Israel held that the exile was ongoing, and that it was the responsibility of their Jewish kin abroad to put it to an end by returning home. To make their points about Jews living abroad, Judean Jews invented the Greek word diaspora, which means something like “to scatter seeds.”

The term first appears in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Torah that is the subject of Aristeas’s story. While The Letter of Aristeas may have embellished the positive relations between Judean and Egyptian Jews, the historical core of the story — which recalls how the Hebrew Torah was translated into Greek by Judean scholars who traveled to Egypt sometime in the late third century BCE — is likely true. These scholars invented the word diaspora in their translation of Deuteronomy 28:25, which warns that Israelites who abandon the terms of God’s covenant will be expelled from their land. In the Hebrew Masoretic version of the Torah, the Israelites are told that they will be a “source of horror” (za’awah) to the foreign nations. In the Septuagint’s Greek version, this horror is rendered as diaspora.

From the time it was invented, diaspora was never meant to be a translation of golah, the Hebrew Bible’s word for the Babylonian exile. And between the two words, diaspora was far worse. Whereas the Hebrew Bible depicts all Judahites being forced into golah in the early sixth century BCE, and indicates that all Judahites were offered an opportunity to return to their ancestral land toward the end of that same century, the word diaspora was meant to split the Jews in half. Some Jews were in it, while others were not. And whereas the golah, according to the biblical prophets, was always meant to end, the Judeans who invented the word diaspora viewed it as open-ended and ongoing.

The Jews who invented diaspora never saw the word catch on. It appears just fifteen times in the Jewish literature that survives from the Second Temple period. Strikingly, nearly all of these appearances come from documents that were produced in the Land of Israel. It seems that Jews in the actual “diaspora” had little use for a word that depicted Jewish life outside the Land of Israel as a monolithic population that stood in opposition to their Judean kin. Yet one thing is certain: Jews on both sides of the diasporic line cared deeply about retaining and honoring their distinctive Jewish identities.