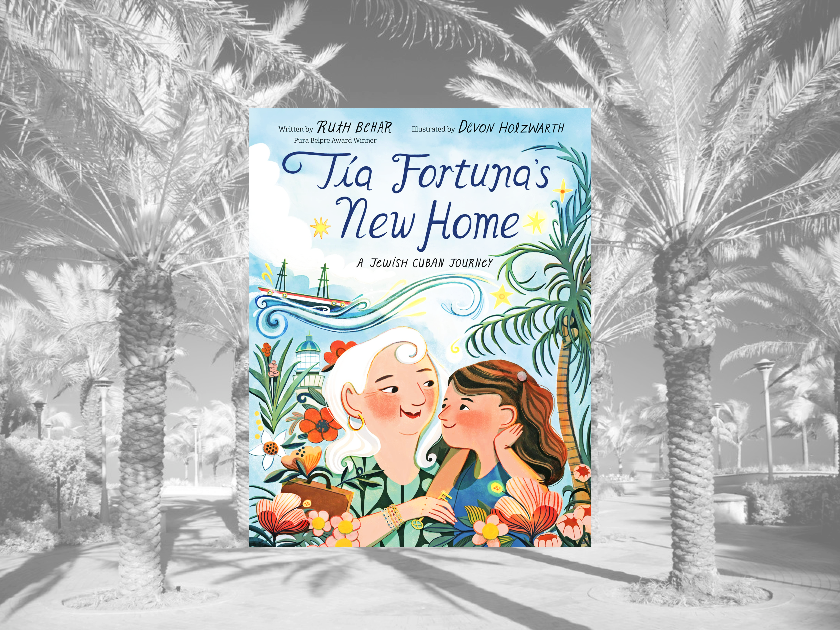

Five years ago, I began to write the story that would become my debut picture book, Tía Fortuna’s New Home; in Spanish, El nuevo hogar de Tía Fortuna. I had a simple goal: to introduce young readers to Sephardic culture as a living culture. Children’s books about Jewish identity tend to focus on Ashkenazi culture. If Sephardic Jews are portrayed at all, they are usually represented as mired in the historical past of medieval Spain. They rarely get to be robustly alive in the present. I wanted to offer a different narrative.

I am Ashkenazi on my mother’s side and Sephardic on my father’s side. My maternal grandparents were from Russia and Poland, my paternal grandparents were from Turkey. On the eve of the Holocaust, they all made their way to Cuba and found refuge on the island. My parents, both born in Cuba, had every expectation they would raise my brother and I in Havana and that we’d stay for many generations. But after the 1959 revolution and the turn to communism, our family left Cuba, along with the majority of the Jewish community — leaving behind synagogues, Torahs, and a world that had seemed permanent. The uprooting was devastating. We’d lost our tropical promised land.

I grew up in New York with both Jewish cultures, hearing Yiddish, Ladino, and Spanish. I was closer to my mother’s side of the family and knew my father’s less well. Still, I was intrigued by the Sephardic culture that I learned about in everyday encounters. For example, my Sephardic Abuela called me Rutika, using a Ladino form of endearment. I loved the Spanish language and was enchanted by the way she and Abuelo spoke; I didn’t know it was called Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, when I was young. Later I realized that the musicality of their Spanish nostalgically recalled Spain, for the Sephardim are a people who kept speaking the language of those who expelled them. That is why the Sephardim have been called “Spaniards without a country.”

Sephardic heritage can be very melancholy. The emotional inheritance of loss and longing — of the legendary expulsion from Spain in 1492 — infuses our songs, or kantikas, in Ladino. Both beautiful and tearful, these melodies are filled with grief about unfulfilled love. I didn’t want to burden children with a sorrowful tale. I needed to find a joyful and poetic way to share what it means to be Sephardic and to connect it with the Cuban heritage through which it had been passed on to me.

Inspired by my relationship with my father’s younger sister, Tía Fanny, I decided to create a fictional story about a little girl named Estrella who has come to help her Sephardic auntie in Miami Beach say goodbye to her pink casita on the beach as she prepares to move to a new home in an assisted living facility. My real-life Sephardic aunt doesn’t live on the beach, but she is a few blocks away from the ocean, and lives by herself. She has no plans of moving to an assisted living facility and was a touch upset that I had dared to imagine her in such a place.

After Tía Fortuna closes the door to her pink casita and pockets the key, she says goodbye to the palm trees and they whisper back adiós, adiós, adios.

In fact, I had visited a home for the aged in Miami and met an elderly Sephardic lady who chose to move there after becoming blind; she felt very well cared for and enjoyed the scent of the flowers in the surrounding garden. I reassured Tía Fanny that my book is a work of fiction and only parts of her life are reflected in the book. One is the lovely tradition she has of serving me potato and cheese borekas whenever I visit her in Miami Beach. These delicious turnovers are the portable food of a people who were forced to move from place to place and find home. The most important ingredient they contain is esperanza, as Tía Fortuna tells Estrella in the book, because their ancestors found hope wherever they went. When I eat borekas with my real-life aunt, she tells me family stories and shares proverbs in Ladino; like little Estrella, I feel myself immersed in the magic and the beauty of Sephardic culture.

As I thought about how to represent Sephardic culture, I also thought about how Miami Beach was changing. This is the section of the city where Cuban Jews found a new home and built Spanish-speaking synagogues recalling the ones they left behind. Over the years, the humble buildings and cottages on the beach where many have lived have been demolished to build luxury residences and hotels. In the past, Sephardic Jews faced the challenge of expulsion, and now many would face the challenge of gentrification.

I decided this would be the case with Tía Fortuna. After losing Cuba, taking the mezuzah and the key to her apartment in Havana as a keepsake, now she must leave her beloved cottage at the Seaway — an actual building that has since been torn down to create multi million dollar apartments at a new complex. Little Estrella is sad and wants to visit Tía Fortuna at the Seaway forever, but her auntie hides her sadness and tells her niece they must enjoy each day as it comes; Tía Fortuna wears several lucky eye bracelets and keeps many hamsas around, praying for mazal bueno.

After Tía Fortuna closes the door to her pink casita and pockets the key, she says goodbye to the palm trees and they whisper back adiós, adiós, adios. Estrella’s mother arrives and they drive off to Tía Fortuna’s new home. Again, Tía Fortuna insists on finding hope and accepting a new beginning. Though now far from the sea, there are banyan trees that she hugs and that whisper back hola, hola, hola. And the butterflies flutter. As Estrella excitedly asks when she can visit again, her auntie whispers, Mashallah, God willing, as my Abuela and Abuelo would say, never assuming another day was a given, treating each day as a blessing.

Just before Estrella departs with her mother, Tía Fortuna gives her a special gift — the key to the Seaway. What better symbol of the Sephardic legacy? The legend goes that the Sephardim took the keys to their houses with them when they left Spain with broken hearts. Even young Estrella has come to understand the loss of home, and how the key can spark memories in our hearts, perhaps the only home that no one can take away from us.

Ruth Behar, the Pura Belpré Award-winning author of Lucky Broken Girl and Letters from Cuba, was born in Havana, Cuba, grew up in New York, and has also lived in Spain and Mexico. Her work also includes poetry, memoir, and the acclaimed travel books An Island Called Home and Traveling Heavy. She was the first Latina to win a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, and other honors include a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship and being named a “Great Immigrant” by the Carnegie Corporation. An anthropology professor at the University of Michigan, she lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.