Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Frankel’s new book High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic hits the shelves this week. Finding the subject more relevant now than he could have expected, Glenn will be guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

I knew I would be running into more than a few Jews three years ago when I started researching a book about the Hollywood blacklist and the making of the classic Western film High Noon. As Neal Gabler chronicles in his landmark book, An Empire of Their Own (1988), most of the moguls who invented Hollywood were Jewish immigrants or the sons of. So were the three filmmakers most responsible for creating High Noon. And at least half the people accused of Communist Party membership or leftist sympathies by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) during its probe of alleged Communist infiltration of the film industry from 1947 to the mid-1950s were of Jewish origin. As I quickly discovered, Jews weren’t just a sub-theme: they were at the heart of my story.

We are 70 years away from when that story began, but the parallels with our own turbulent political times are impossible to ignore. After laying low during much of the New Deal and the struggle against fascism in World War II, the American Right rose up with a vengeance in 1946, sweeping Republicans into power in both houses of Congress and pledging to claw back our country from the traitors and outsiders who had supposedly usurped our government and our culture. The main targets were Communists, liberals, and Jews. With their roots in social democratic movements in Russia, Poland, and other parts of Eastern Europe, many Jews fit snugly into the various segments of the American Left and were easy scapegoats for the new Red Scare.

Jews reacted in all kinds of ways to the HUAC inquisition. Faced with the loss of their careers and incomes and alienated from their former comrades in the American Communist Party, large numbers signed loyalty oaths and denounced the party, praising the Committee for its investigative work and naming names of purported Communists past and present. The studio moguls, fearful of being accused of Communist sympathies, aided and abetted those who cooperated and set up the blacklist process to punish those who refused.

But the majority of those called to testify refused to cooperate, and many of them spent a decade or more without meaningful work in Hollywood. Six of the original Hollywood Ten who were imprisoned for defying the Committee during the 1947 hearings were of Jewish origin — yet so were 10 of the 15 movie producers who signed a public statement condemning the Ten and establishing the blacklist; indeed, the chairman of the Committee that drafted the statement was Mendel Silverberg, an entertainment lawyer and the unofficial leader of Hollywood’s Jewish community.

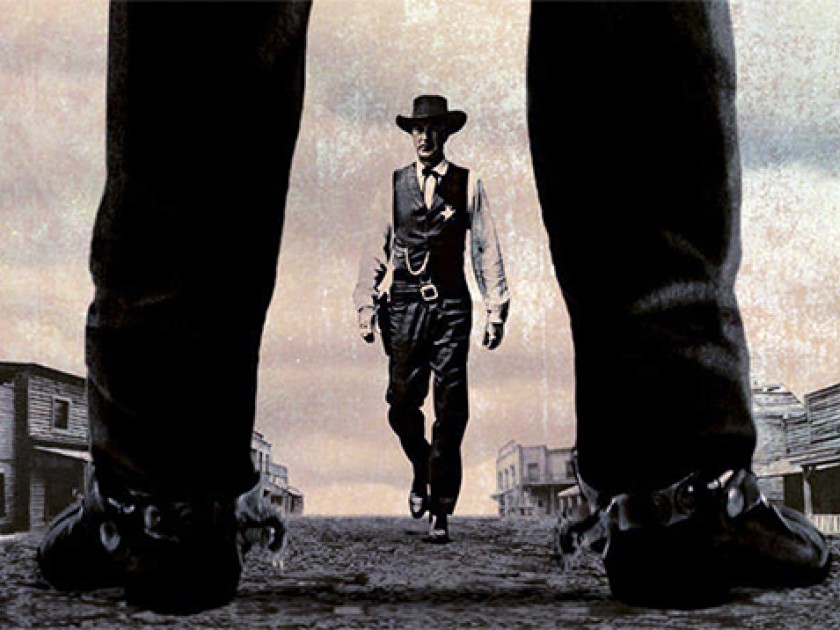

Screenwriter Carl Foreman, the Chicago-born son of Russian Jewish immigrants, was called to testify about his ties to the Communist Party during HUAC’s second round of public hearings in 1951. A gifted writer who had recently been nominated for two Oscars for his screenplays, Foreman was in the middle of finishing the final draft of High Noon. He turned his script into an allegory about the Red Scare and the Hollywood blacklist, seeing himself as the lone marshal and the HUAC inquisitors as the gang coming to town to kill him while cowardly community leaders abandon him to meet his fate alone. In the end, Foreman refused to name names, was blacklisted and forced to seek work in England, where he lived for 25 years in a form of political exile.

The blacklist did huge damage to families, friendships and careers, and left wounds that remain unhealed three generations later. It is hard to make moral judgments about the men and women who faced the inquisition, but there is no question that the blacklist was in many ways a Jewish affair and a challenge to Jewish community’s conscience, which may soon be called upon again.

Glenn Frankel worked for many years for The Washington Post, serving as bureau chief in London, Southern Africa, and Jerusalem, where he won the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. He has taught journalism at Stanford University and the University of Texas at Austin, where he directed the School of Journalism. He is the author of five books, has won a National Jewish Book Award, and was a finalist for The Los Angeles Times Book Prize. He has been a Motion Picture Academy Film Scholar and a research fellow at the Leon Levy Center for Biography at the City University of New York. Rivonia’s Children, first published in 1999 and republished in 2024 by Blue Ear Books, was a finalist for the Alan Paton Prize, South Africa’s highest honor for nonfiction.