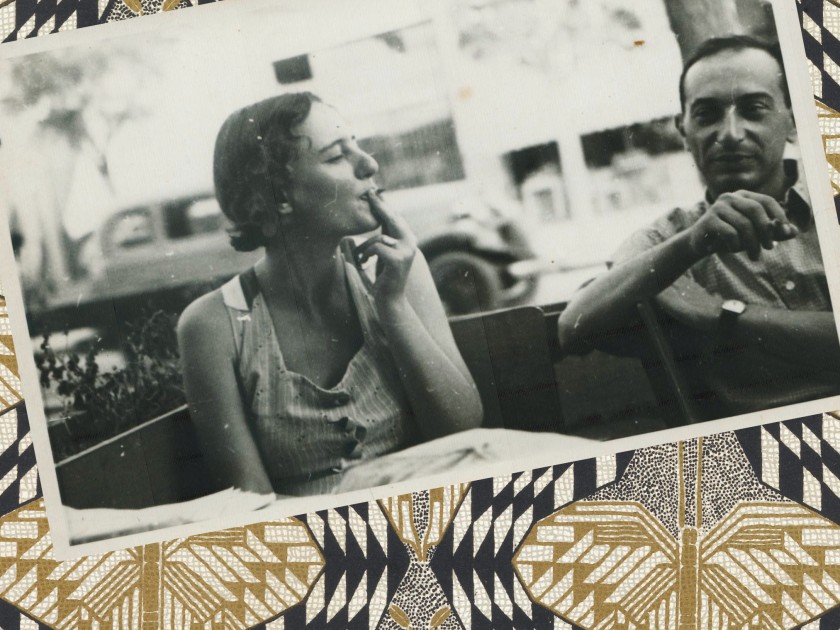

Photo: Leah Goldberg and the writer Ya’acov Horowitz, 1935. Courtesy of the Gnazim Archive and Yair Landau. Background: “Tapete Goldene Schmetterlinge” (“Golden Butterfly Wallpaper”), from Die Quelle: Flächen Schmuck (The Source: Ornament for Flat Surfaces), 1901, Austria. Gift of Jerrol E. Golden to Cooper Hewitt. Illustration: Katherine Messenger

Where did Jewish writers and intellectuals who migrated to large cities at the turn of the twentieth century find inspiration and a place to meet others? The answer was often the coffeehouse. Indeed, the draw of cafes was so strong that they became a key site for the creation of modern Jewish culture.

In theory, coffeehouses — from their early years in the Ottoman Empire, to later, as they spread throughout Europe — were open to everyone. This inclusivity was one of the reasons they attracted so many modern Jews in various cities in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. That said, they were mostly masculine spaces, especially those known as “literary cafes.” Many Jewish habitues of the cafe described it as a modern, secular substitute for the traditional house of study — the older and more established writer had the status of the rabbi; his cafe table was akin to the rebbe’s tish; and his students, just like a rabbi’s, would gather around to listen to his words. Instead of Talmud or Midrash, this secularized rabbi and his followers would analyze and discuss a poem or story. Not only did the debates in these cafes have the flavor of the yeshivas and houses of study where some of the participants had spent their youth; the male camaraderie of traditional Jewish society was very much part of the experience as well.

Where were Jewish women in the coffeehouse? Was there a place for them in cafe culture?

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Jewish women such as Fanny von Arnstein, Rahel Varnhagen, and Dorothea von Schlegel (Moses Mendelssohn’s daughter) found a new role outside the patriarchal structures of their families as hostesses of salons. But these women were quite exceptional, and the fact that they were Jewish as well as female meant that their outsider status was guaranteed. Nevertheless, as the idea of the “new woman” spread to Jewish society in Eastern and Central Europe, the United States, and the Middle East, it was felt in the coffeehouses as well. Women were often café servers; sometimes they were owners or customers. In a few establishments, like Cafe Fanconi in Odessa, there was something akin to a “women’s section,” created ad hoc by those who ventured into this new, alluring space at the beginning of the twentieth century. However, a woman sitting alone was a rare sight, often considered suspicious.

The presence of women in the cafe was met with curiosity, desire, and frustration by male habitues and writers, who tried to explain and define these modern women. In 1905, Abraham H. Fromenson, describing the “politically radical cafes” of New York’s Lower East Side, declared, “where the cigarette smoke is thickest and denunciation of the present forms of government loudest, there you find women!”

Fromenson was referring to women like Emma Goldman, known as “red Emma,” or “the most dangerous woman in America.” In 1889, when she was twenty years old, Goldman spent her first day in New York City. Hillel Solotaroff, a Russian-born Jewish anarchist, took her to Sachs’s Cafe, which, as he informed her, was “the headquarters of the East Side radicals, socialists, and anarchists, as well as of the young Yiddish writers and poets.” Goldman later recalled how, for one who had just come from the provincial town of Rochester, the noise and turmoil at Sachs’s Cafe was intimidating. And yet, she saw her initiation there as establishing her lifelong intellectual and political engagement.

Another extraordinary woman in New York’s cafe scene was the poet Rosa Lebensboym, best known by the pen name Anna Margolin. In 1913, she settled in the city and joined the staff of the Yiddish newspaper Der tog, for which she wrote a weekly women’s column. When she began publishing modernist Yiddish poetry under her pen name in the 1920s, it aroused much attention — many believed that the mysterious poet was really a man. Ironically, success as an author meant some degree of anonymity. One of Margolin’s works is an exquisite cycle of poems entitled In kafe (“In the Café”), which starts with the line, “Now alone in the cafe.”

In Berlin, the German Jewish poet Else Lasker-Schuler was part of the expressionist circle of writers and artists nicknamed “Cafe Megalomania.” She recorded an imagined world in vivid poems, sketches, and an epistolary novel, My Heart. She also played with identity and conceptions of gender by dressing up as her masculine or androgynous literary characters, such as Prince Jussuf of Thebes. As a modern Jewish woman and writer, Lasker-Schuler was included in cafe culture, yet regarded with uncertainty. A friend of hers, the anarchist Gustav Landauer, confirmed that “she doesn’t fit anywhere and certainly not in the milieu in which you see her.”

The poet and writer Leah Goldberg met Lasker-Schuler in Jerusalem’s Café Sichel in the 1940s. (They could have met a decade before at Berlin’s Romanisches Cafe, but the young Goldberg first went there as a student just before Hitler rose to power, when Lasker-Schuler had stopped frequenting it.) Goldberg immigrated to Tel Aviv in 1935, and quickly became part of a literary and social circle that included some of the most important Hebrew writers of the 1930s and 1940s, who met in coffeehouses. Still, as a woman, she was viewed as separate and different. In 1971, the editor and critic Israel Zmora wrote, “In most cases, the habitues of the cafe were all men. Women writers were very few … Leah Goldberg was the exception. She used to go to the cafe almost daily, but on her own, and only occasionally mix with all of us.”

Goldman, Goldberg, Margolin, Lasker-Schuler and others shared the experience of exceptionality within a predominantly masculine milieu. These newcomers to the café — writers, performers, radicals — were marginalized not only due to their gender, but often also as Jewish migrants crossing borders of language, ideology, and space.

Shachar Pinsker is the author of A Rich Brew: How Cafes Created Modern Jewish Culture and Literary Passports: The Making of Modernist Hebrew Fiction in Europe. He is Associate Professor of Hebrew Literature and Culture at the University of Michigan.