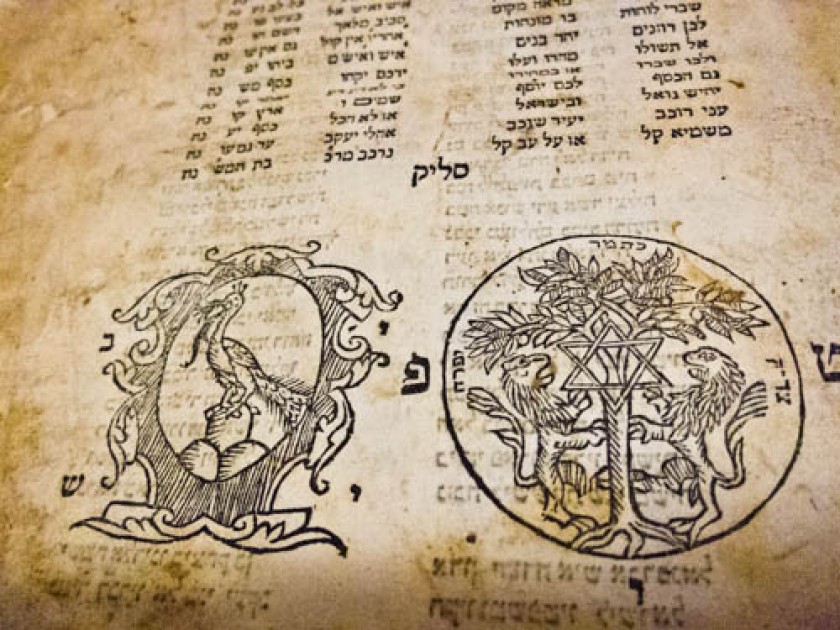

Picture of the I Fratelli Foa colophon (or printer’s mark) in a book.

My father, an Italian Jew, used to say that “family is everything,” yet I knew very little about the history of the Foà family. That changed when, in his retirement, my father wrote a forty-page family memoir and began to fill in some of the missing pieces. He devoted only one line to our most famous ancestors, I Fratelli Foà, printers of Bibles and Hebrew prayer books in sixteenth century northern Italy. They flourished between 1551 and 1590 in the tiny, walled city of Sabbioneta. I’d become aware of them when, a decade earlier, an Israeli cousin had sent me copies of their handsome printer’s mark, or colophon. Their books are still considered exceptionally beautiful.

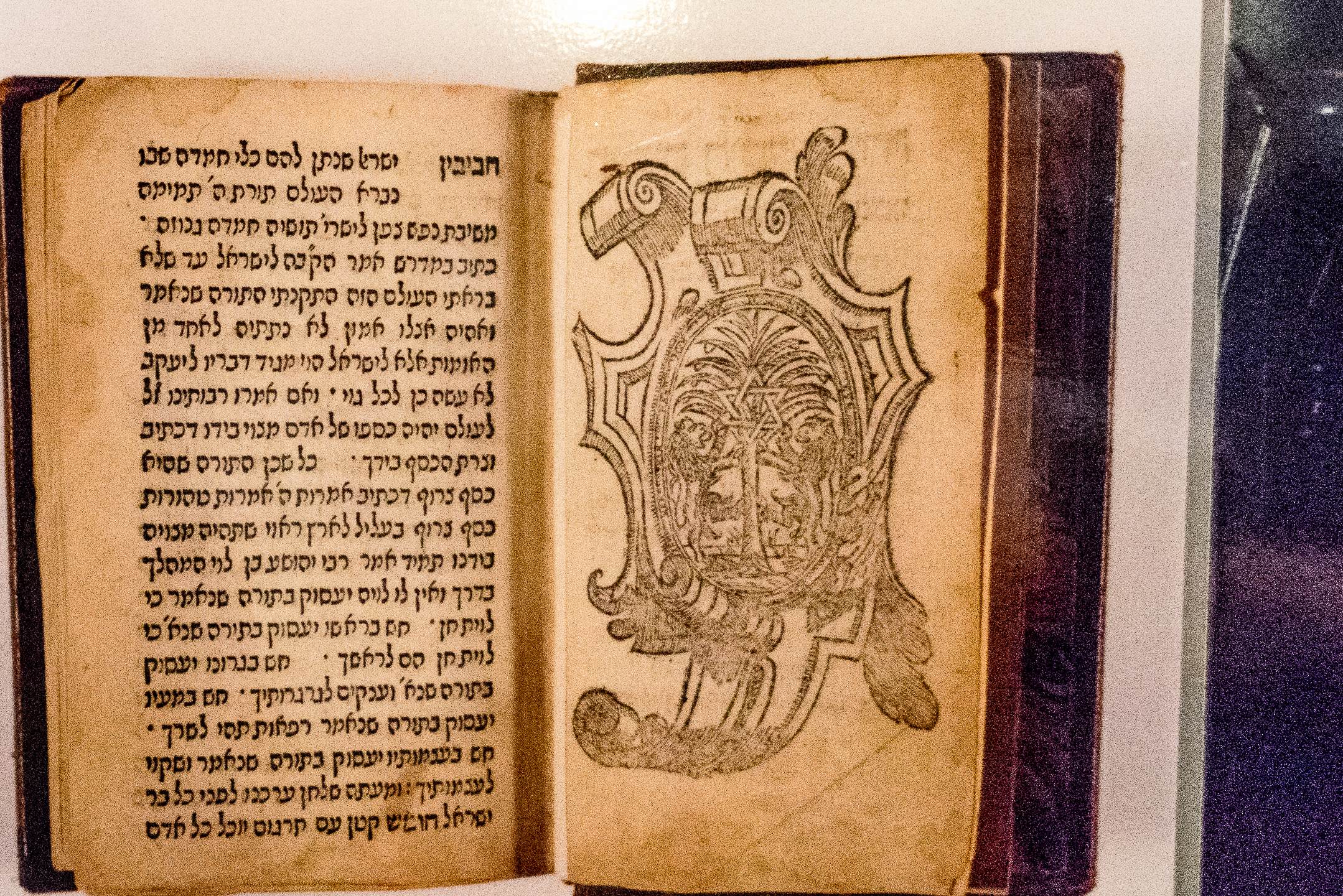

Picture of the I Fratelli Foa colophon (or printer’s mark) in a book.

After my parents died, I proposed to my sister that we take a trip to Italy to visit those villages where the Foàs first emerged from the fog of history. As a writer, I took particular pride in our printer ancestors who peddled, not rags, but books. Perhaps, too, the existence of these printers helped explain why my father and his entire family believed that the Foàs were special.

Of all the villages we visited, tiny Sabbioneta is the one I fell in love with. It’s an exquisite Renaissance walled city. So perfect and beautiful are the proportions of its two town squares that, when we drove through its red brick outer city walls, I thought I was on a BBC movie set filming a new version of “Romeo and Juliet.” It’s a magical place.

When we mentioned to a woman in the tourist office that we were the Foàs in search of our family history, she immediately rung up someone who she said is extremely knowledgeable about the Jews of Sabbioneta. Within minutes Alberto Sarzi Madidini turns up, a non-Jewish resident of the city whose passion is researching and writing about the Jewish history in his hometown. He is eager to show us the synagogue, and drives us to the Jewish cemetery. During two subsequent visits and research of my own, I discovered much more about the Sabbioneta Foàs who, it turns out, were fortunate in many ways.

The restored synagogue in Sabbioneta.

First, they were lucky to have lived under the liberal rule of Vespasiano Gonzaga (1531 – 1591), the Duke of Sabbioneta. An enlightened ruler, educated in Greek, Latin, history, Italian literature, the Talmud, and even Kabbalah, he was raised to be both a soldier of fortune and true Renaissance prince. Gonzaga wanted to make Sabbioneta a capital of the mind. He not only permitted the rise of the Foà printing house, but also remained an enlightened protector of the Jews. In fact, as I later discovered, Sabbioneta is the only city in Italy (with the exception of Livorno) that never established a Jewish ghetto. Gonzaga welcomed and respected Jews as “people of the book,” at a time when other cities created ghettos and forced Jewish printers to close.

They were also fortunate that Rabbi Tobia Foà, a man of exceptional culture and good deeds, established the press. According to David Amran, author of The Makers of Hebrew Books in Italy, “No Hebrew press of the century was more fortunate in the number and quality of its workmen.”

My growing curiosity about our printer ancestors led me to educate myself about the history of printing and its migration from Germany to Italy. It’s a history with some surprises.

I did not know, for example, that although Jews helped finance Gutenberg’s 1450 invention — first used to print a Bible in 1455 — they were not permitted to join German printing guilds. So German Jews took their knowledge to Italy where, as early as 1470 in Rome, Christian and Jewish printers were established. Nor did I realize that, even in Italy, the privilege of printing books was never conferred upon a Jew. Only members of patrician houses could establish presses. This explains why Jews partnered with families like the Gonzagas. Even so, licenses to publish Hebrew books were granted and revoked at the whim of local rulers and the pope. In fact, only a short window of time existed during which the church allowed Jewish printers to pursue their trade in Italy. The situation varied from city-state to city-state.

I also had no idea that book burning was such an ancient practice. In 1554, for example, Julius III issued a Papal bull to the effect that all Jewish texts, the Talmud in particular, should be burned. The practice had already begun with a bonfire of books in Rome’s Campo de Fiori. In Venice alone, thousands of books were thrown into the flames in St. Mark’s Square. Very few books survived. Those that did, ironically, were often saved by monks and tucked away in monasteries.

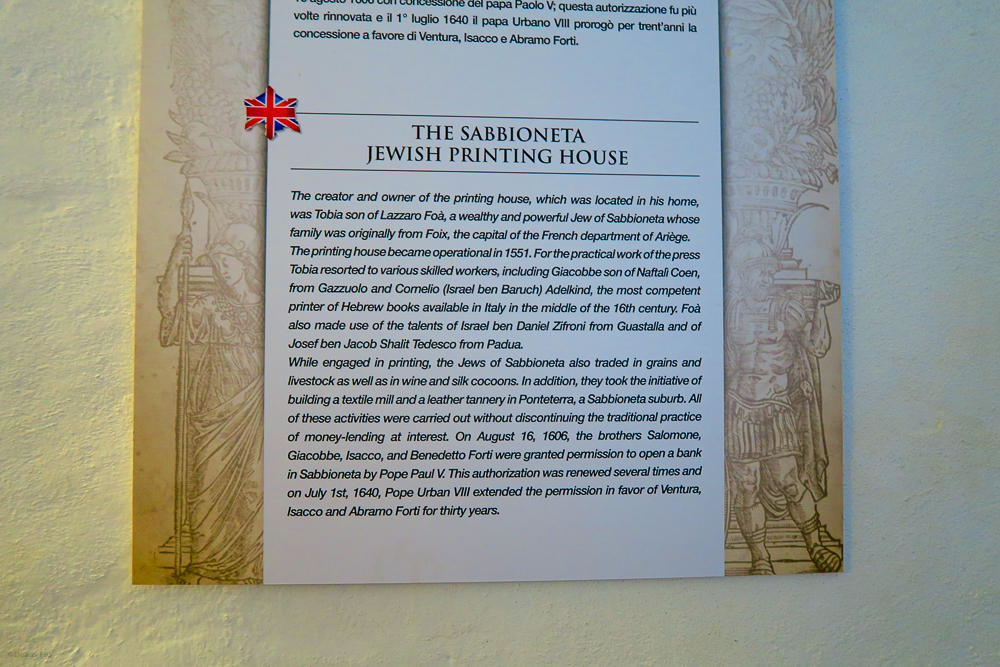

Information about the I Fratelli Foa printing house in Sabbioneta that is displayed outside the synagogue to inform visitors of

their importance.

Six years after my first visit to Sabbioneta, I discovered that Columbia University Press owns the third largest collection of Judaica manuscripts in the country, outside of a religious institution. It was mounting an exhibit called, “People in the Books: Hebraica and Judaica,” and on a hunch, I called the curator, Michelle Chesner, to find out whether they might have an I Fratelli Foàbook in their collection. To my astonishment, they did. I arranged a visit to the library and spent a long time looking at, handling and photographing the book. Though its cover was missing, it was fascinating to turn its pages, some unusually laid out like inverted pyramids, and others bearing black censored lines and sections. I did not know that books that escaped incineration were routinely censored and that Jews who converted to Catholicism often became official censors, in part because they were the only ones who could read Hebrew. (Show the two printers marks on the last page of the book?) Curator Chesner also informed me that other Foà printers continued to carry on the family profession in eighteenth century Amsterdam, Venice and Turkey. Their work contributed significantly to the diffusion of Jewish literature in Europe.

Since my first visit to Sabbioneta, and despite a 2012 earthquake that damaged the synagogue, the city was named a World Heritage Site. Funds were raised to continue the synagogue’s restoration and clean-up of the cemetery. New historic artifacts, including glass mezuzahs, probably made from Venetian glass, are on display in several cases devoted to the town’s collection of Jewish and Christian artifacts. And standing at the entrance to the synagogue are two informative narratives: one on “The Sabbioneta Jewish Printing House,” and the other on “The Jewish Community in Sabbioneta.”

Four years after my initial trip to Italy, I took the elevator to the top floor of Sotheby’s, the New York auction house, to visit the world’s largest collection of Jewish books, the Valmadonna Trust Library. It was a mob scene. Guides were giving tours of the floor-to-ceiling shelves of books — 13,000 volumes — from every corner of the Jewish diaspora. Near the shelves of Italian books were two long glass vitrines with a handful of books, some open and some closed, on view for further inspection. And there, thrillingly, were two exquisitely preserved I Fratelli Foàbooks. One was especially beautiful; a small traveling Torah with a hand-tooled tapestry-embroidered cover. The other was open to the I Fratelli Foà colophon: the black lustrous image of a palm tree, Star of David, two rising Lions of Judah and the Foà name in Hebrew. It looked so fresh, as if it had just been printed.

Picture of the colophon painted on the ceiling of a home that has just been renovated.

Overwhelmed, I couldn’t help but wonder why, out of the thousands of books in this collection, Lunzer chose to display the works of my ancestors. I felt compelled to ask him myself. Threading my way through the crowd, I moved closer, placed my hand on his arm and quietly introduced myself to the eighty-five-year-old bibliophile as a Foà. Lunzer suddenly looked up. “A Sabbioneta Foà?” he asked. I nodded. “You’ve been to Sabbioneta?” I nodded. He smiled, raised my hand to his mouth and, in a gesture worthy of an Italian aristocrat, kissed it.

“You come from a wonderful family,” he said.

Eleanor Foa is an author, journalist, and corporate writer. Her memoir MIXED MESSAGES: Reflections on an Italian Jewish Family and Exile was published in November 2019. Her work appears in national newspapers, magazines and websites. She is the author of Whither Thou Goest and In Good Company, President of Eleanor Foa Associates (eleanorfoa.com), past president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and received literary residencies at Yaddo and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts.