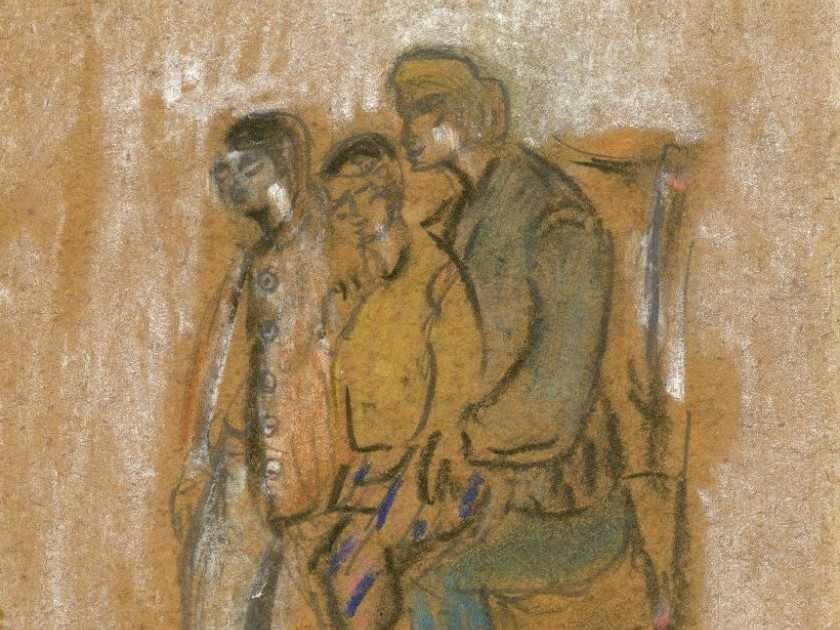

“My dearest Gewereth Wormser and her two dear boys,” Else Lasker-Schüler

From the collection of the National Library of Israel

When I moved from London to Berlin in 2006, I arrived with conversational yet grammatically impaired German. To finally pick apart my der die das from my dem der dem I enrolled at a language school in the Schöneberg district, the Hartnackschule (and yes, the English-speaking students called it the “School of Hart Nacks”). Next to the school was a hotel, guarded by a plaque bearing the name of a woman who certainly knew the Hart Nack life: Else Lasker-Schüler.

It was a name I barely recognized at the time, but as I turned to literary translation some years later, the writer and artist who witnessed almost the entire Weimar Republic from room seventy-four of the Hotel Sachsenhof also took up lodgings in my imagination. The latest product of this obsession over Else Lasker-Schüler is a translation project, Three Prose Works. It collates autobiographically charged publications that Lasker-Schüler originally issued prior to World War I — sketches, stories, and fables which together represent a kaleidoscopic account of her development as an independent woman and creative force.

Born in 1869 to an assimilated Jewish family in Wuppertal — an industrial western German city — Lasker-Schüler made her own entrée to Berlin in 1894 with her physician husband, Berthold Lasker. However, as the twentieth century dawned Lasker-Schüler had a child with another man and left the bourgeois security of her old life, throwing her lot in with Berlin’s creative underground. She was particularly close to the apostolic arch-bohemian writer Peter Hille; he called her “Tino” and the “Black Swan of Israel”, and she immortalized her mentor in her first book of prose, The Peter Hille Book.

Along with her second husband Herwarth Walden, Lasker-Schüler was at the forefront of Expressionism, almost a lone female voice in the emerging literary movement.

Lasker-Schüler was also a highly accomplished visual artist but it is verse for which she was best known, and her readers, a select few to begin with, recognized her as an uncommonly brilliant poet — fearless, original, passionate. Verses like “End of the World”, with its erotic eschatology, foretold a new mode in German letters. Common to all her means of expression was an elaborate world-building inspired by the Torah, 1001 Nights, and the Orientalist motifs ubiquitous throughout early twentieth-century German culture. In a time of rising antisemitism she defiantly adopted the offensive label of “Oriental” for herself, proposing the rebellious figure of the “wild Jew” as a counter-argument to assimilation. In her work she adopted evocative signifiers of lands she had never seen, and refashioned them at will. Associates found themselves thinly fictionalized in Lasker-Schüler’s Semitic realm while the writer’s own avatars cycled through gender, sexuality, and ethnicity, the most consistent persona being the Baghdadi warrior princess, “Tino”. It was a role she lived day to day, dressed in harem pants and costume jewelry; while it would be tempting to claim that her persona was her greatest creation, that would diminish both the stature of her art and the fluidity of the borders between artifice and the actual in her life.

Along with her second husband Herwarth Walden, Lasker-Schüler was at the forefront of Expressionism, almost a lone female voice in the emerging literary movement. Lasker-Schüler never remarried after they divorced in 1912, and with the notoriously low pay scale attached to the position of bohemian poet, her life assumed a pattern of habitual poverty, begging letters, and brief periods of respite. As World War I ended and the Weimar Republic began, Lasker-Schüler entered a productive period which yielded verse, fiction, drama, essays and artworks. But life slowed as her son Paul fell ill, stopping completely when he died in 1927, aged just twenty-eight. And then just as she received a prestigious literary prize in 1932, signaling long-withheld recognition from the establishment, that establishment underwent a catastrophic transformation: the Nazi regime.

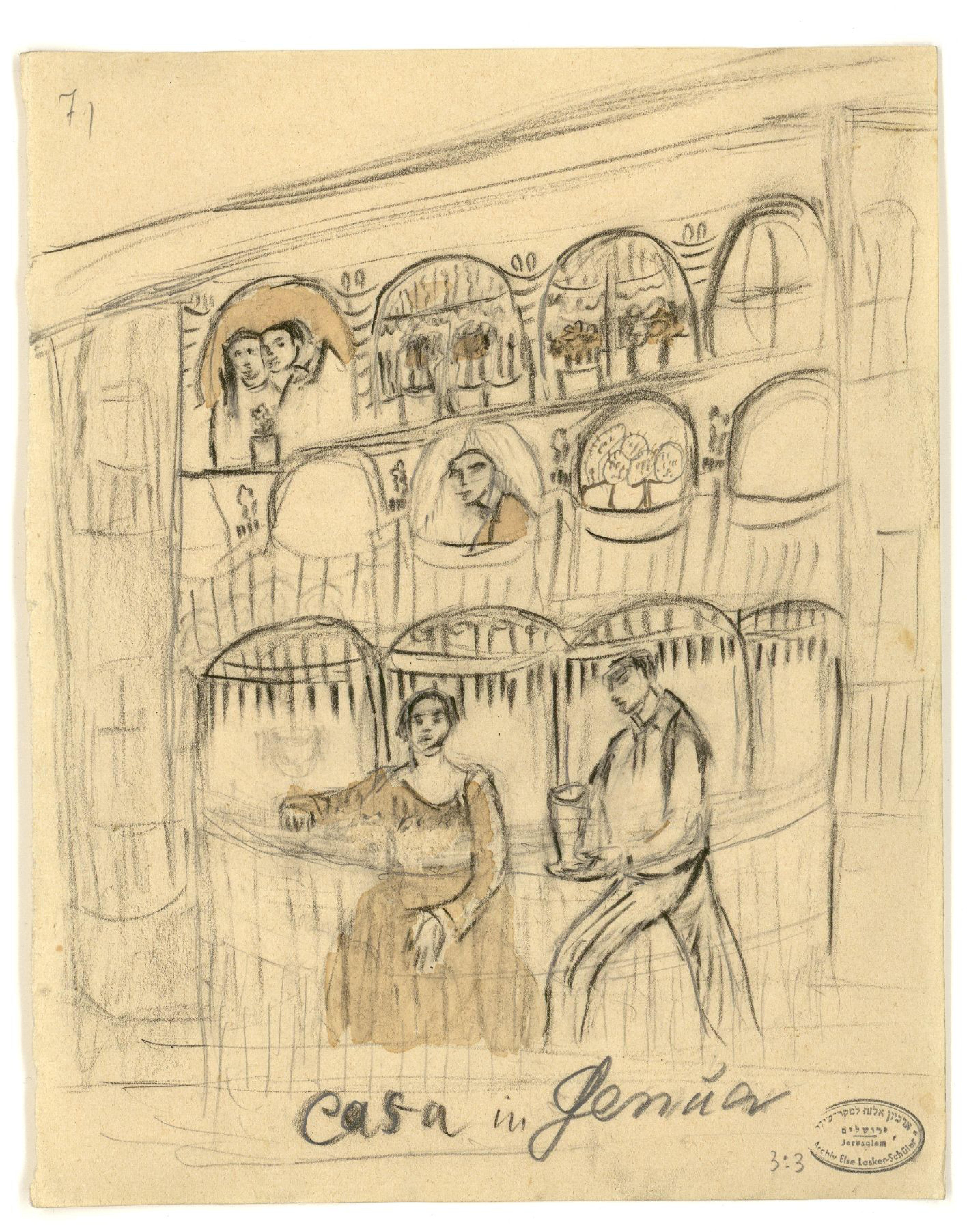

Casa in Genua, Else Lasker-Schüler

From the collection of the National Library of Israel

Shortly after the Nazi takeover in 1933, Lasker-Schüler checked out of the Hotel Sachsenhof and left Germany, never to return. After living in Zurich under harsh conditions and the constant threat of deportation, she was visiting Palestine in 1939 when World War Two broke out. With return to Switzerland now barred to her, she was finally experiencing the lands to which her imagination had so often gravitated, but with the luxury of recasting them no longer available. Instead it was her family, her childhood home, a whole vanished world that now became the unattainable ideal, a longing distilled in the heartsick late verse, “My Blue Piano”. With just thirteen lines and complete mastery of form, the poet imagines the rats of the Reich dancing across the strings of her abandoned instrument. Sadly she didn’t live long enough to see the rats vanquished; Else Lasker-Schüler died in Jerusalem in January 1945 and she was laid to rest on the Mount of Olives.

In Germany Else Lasker-Schüler is now celebrated as one of the country’s finest poets, her verse set in school curricula and collected in dozens of different editions. Yet she remains largely unknown in the Anglosphere. The only English-language biography of note appeared almost twenty years ago and her works — fitfully translated — tend to be issued by smaller university presses. Yet Lasker-Schüler’s writing is not “difficult” or willfully obscure, instead offering powerful emotional immediacy and universal themes: romantic love and sensual desire, the quest for home and solace, purpose and transcendence.

Else Lasker-Schüler never wrote her memoirs, but in the glittering mosaic of Three Prose Works we have the origin story of a blazingly unique life which deserves far greater recognition.

James J. Conway was born in Sydney and now lives in Berlin where he is a translator from German to English, both commercial and literary. He has translated and published eight books for Rixdorf Editions, including Berlin’s Third Sex (Magnus Hirschfeld), Antisemitism (Hermann Bahr) and Death (Anna Croissant-Rust). He has written for outlets such as the Times Literary Supplement, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Public Domain Review, as well as his own repository of alternative cultural history, Strange Flowers.