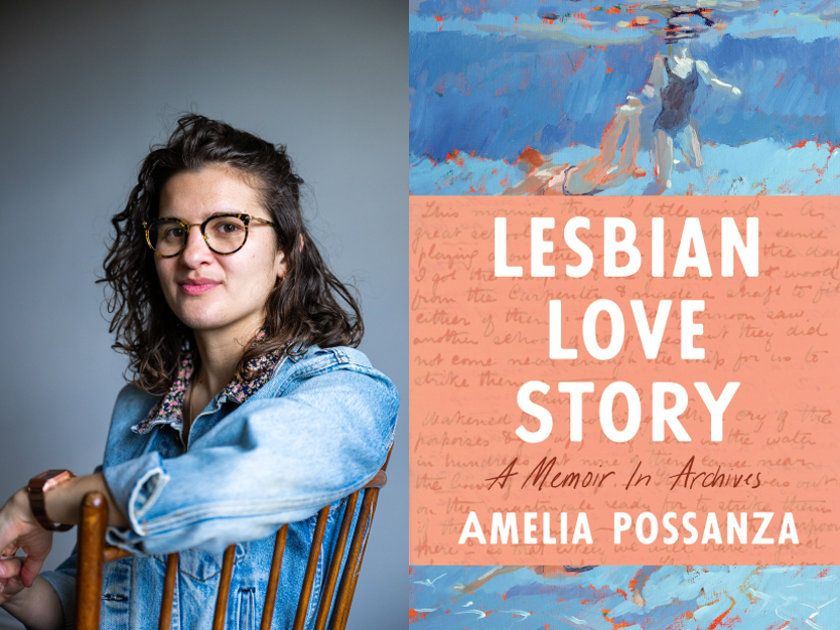

Author photo by Becca Farsace

Amelia Possanza’s new book Lesbian Love Story blends memoir with historical archival research to highlight stories of lesbian love in the twentieth century. Lesbian Love Story is a wonderful romp through lesbian history that illuminates contemporary lesbian life and grapples with questions of how to tend to and care for the past.

In this interview Possanza discusses love, archives, Jewish lesbians, and the history of New Amsterdam.

Julie R. Enszer: Amelia, one of the things that I just adored about reading and rereading this book is the way you fall in love with your subjects. In some ways, the real lesbian love story of the book is your love story with your subjects. When and how did you fall in love with these characters?

Amelia Possanza: I’ve always had a big heart, and while it’s gotten me into a lot of trouble in my romantic life, it was certainly helpful in the process of researching and writing the book. I can’t remember the exact moment I fell for these historical figures, but I’m sure my friends began to notice all the tell-tale signs before I did: casually dropping their names into conversation at every opportunity, staying up late to listen to their voices on oral history tapes, biking entirely too far in the hopes of a chance encounter (at the New-York Historical Society.)

I went into this project at a time in my life when I was in search of a fairly traditional kind of romantic love and partnership, but my subjects had something else in mind. The lesbians in this book — particularly Joan Nestle, one of the founders of the Lesbian Herstory Archive and a fellow Jew — taught me that caretaking is one of the ultimate expressions of love. Joan practiced this when she interviewed Mabel Hampton–a Black stud who danced during the Harlem Renaissance, helped found the LHA (Lesbian Herstory Archives), and has the starring role in Chapter 2 of my book – for a series of oral history tapes. She wrote Mabel one of the most romantic postcards I have ever read, even though theirs was not a traditional rom-com sort of love: “I am going to buy a mountain here for us. Would you like to live in the Alps?”

Tending to the archive, studying the intimate details of the personal lives of the lesbians who came before me and trying to tell their stories in a way that stays true to their lives, it’s almost impossible for that not to become a practice of love.

JRE: Are there other historical characters who you are in love with that didn’t make the cut for the book?

AP: Ever since the book came out, folks have been passing along the names of folks who I wish I could have included, such as Victorian-era photographer and co-founder of the Staten Island Bicycle Club Alice Austen, whose former home has been turned into a beautiful museum; New York City physician and public health advocate who spent her later years with a “woman-oriented woman” Sara Josephine Baker; and Rusty Mae Moore and Chelsea Goodwin, founders of Transy House, a 1990s refuge for unhoused gender non-conforming people and the last place where queer liberation pioneer Sylvia Rivera lived. I’m desperate to know what was going on in environmentalist Rachel Carson’s romantic life, when she wasn’t busy writing Silent Spring!

Someone recently asked a question that truly stumped me: if you were to write a sequel to this book fifty years from now, who from the twenty-first century would make the cut? That question has me jotting down names from an entirely different era, and thinking about how social media, celebrity culture, and everyone being very much online have generated an unprecedented amount of archival material, also known as content, and yet somehow all that noise has drowned out the realities of everyday queer lives.

JRE: This book highlights the ways that histories and stories of people from the past can become beacons for people living today. In writing about Mabel Hampton, you confide, “what I truly want is for her to guide me through the now, to be the dead who takes care of me, the living.” How did you come to think about history as instructive to the present?

AP: I fell in love with Mabel, and also with one of her catchphrases, which I still hear in my head: “The dead take care of me, and so do the living.” No matter what your politics are, it’s hard to deny that we’re facing some enormous challenges. It’s going to be a lot harder to confront those challenges (even if they’re just personal dating challenges) if we stay disconnected from the stories of the generations who came before us. As I researched the book, I was often astonished by the resonances between the lives of these twentieth century lesbians and today’s headlines. These lesbians were arrested for wearing clothes that did not correspond with their perceived gender. Their stories were yanked out of libraries and banned from being mailed across state lines. When I feel hopeless about the fact that these are still issues we’re struggling against today, I remind myself that we don’t have to resolve them on our own. We don’t have to be, as Cherríe Moraga, one of the lesbians in the book puts it, “ever-inventors of our revolution.” There is a long history of activism and resistance that we can draw from.

JRE: Another element of Lesbian Love Story that resonated powerfully with me is the way you help readers to understand kinship expansively. This is particularly true in the final story of Amy Hoffman’s relationship with Mike Riegle, which she wrote about in Hospital Time. Talk to me a bit about kinship and how you see it as a part of lesbian love stories.

AP: This book was borne out of my frustration with the gay men on my swim team and some of the rude things they’ve said to me over the years about lesbians. I’ll spare you the details! In spite of that frustration, those men are all dear friends of mine and make up a huge part of my community. Amy had her own frustrations with Mike, and at the height of them, called him “such an asshole.” Kinship is often about caretaking, even for people who aren’t your blood relatives, even for people who infuriate you. Because lesbians couldn’t rely on the state, which often worked to institutionalize them, or on their blood relations, they built new connections when they needed support, often with other queer people. They remind us to ask, what would the world look like if we treated all people as worthy of care and support?

I have my queer community in the present, but I also wanted to find a queer community that stretched across time, to situate myself among lesbians.

JRE: One of the tangles that endlessly fascinates me is the relationship between archive, history, genealogy, biography, and autobiography. You bring to this tangle many lovely innovations through your selection and curations of stories. Can you reflect on those relationships?

AP: There’s a quote from Heather Love that I found after I finished the book that answers this question better than I ever could: “The longing for queer community across time is a crucial feature of queer historical experience, one produced by the historical isolation of individual queers as well as by the damaged quality of the historical archive.” I have my queer community in the present, but I also wanted to find a queer community that stretched across time, to situate myself among lesbians. I wouldn’t be able to be a lesbian in the way I am today — short hair, pants, ordering a Dyke beer at a dyke bar — without everyone who came before. I imagine a lot of identity groups long to feel that kind of historical kinship.

JRE: There are many Jews in these stories. Can you talk a bit about what you hope Jewish readers will take away from this book?

AP:Sarah Schulman, another Jewish lesbian who makes only the briefest appearance in the book, once said that the great loss of stories during the Holocaust was part of what motivated her to start the ACT UP Oral History Project, which eventually became a book, Let the Record Show. I asked Joan [Nestle] and Amy [Hoffman] if their own archival impulse came from that same history, and they both said no. For Joan, it grew out of her love of other people’s stories, and also out of her own marginalized background. My Jewish heritage has pushed me to think a lot about how to reconcile the hate,trauma, and violence that has left a mark on my family tree with the abundance I experience in my everyday life. I hope that Jewish readers will reflect on how their own histories might inform the support of other persecuted communities.

JRE: Can you talk about your Jewish story?

AP: A lot of friends told me they didn’t know I had Jewish heritage until they read the book! I never had a Bat Mitzvah, but I grew up in Squirrel Hill, swam for the Jewish Community Center, and went to temple every weekend for about two years in middle school to watch my friends read their Torah portions. I’m not a practicing Jew, but all of these experiences have made the culture very important to me. It’s an easy explanation for my anxiety, and for my love of rugelach. In some ways, for me, being a Jew is a bit like being a lesbian. Jewish is both a religion and an ethnicity, and there’s no one right way to become a part of the community. Sometimes, all it takes is claiming that identity.

JRE: The book covers the entire twentieth century and brings together a wonderful, multicultural cast of characters. The epilogue is titled “The Lesbian Future.” What are some of your greatest hopes for lesbian futures?

AP: I started this project as a hopeless romantic, and then somewhere along the way I became a political radical. My idea for “The Lesbian Future” came from Gloria Anzaldúa’s vision for The Left-Handed World, a world where “the colored, the queer, the poor, the female, the physically challenged” would be empowered. Mainstream lesbian acceptance, which we see quite a bit of today, would not have solved all the difficulties the historical figures I studied encountered in their lives. Mabel Hampton worked her entire life – “Right up until I pass away, I’m still working” – and yet she still could not afford a decent apartment for her and Lillian to live in. As a young girl, Gloria Anzaldúa was hit with a ruler when she spoke Spanish in class. What would “acceptance” do for them? They pushed me to demand nothing short of a revolution, and their stories (I like to think) provide some inspiration for how we might begin to imagine that.

JRE: Now that the book is out, what are some of your current obsessions?

AP: Oysters. The colonization of this country and the history of New Amsterdam, which eventually became New York City. I’m living on this archipelago of islands that I love so deeply, and trying to come to terms with the fact that it’s likely going to sink back into the ocean someday soon. How did we decimate a landscape once described as “Eden” in under 500 years? Is there any hope to be found?

Julie R. Enszer is the author of four poetry collections, including Avowed, and the editor of OutWrite: The Speeches that Shaped LGBTQ Literary Culture, Fire-Rimmed Eden: Selected Poems by Lynn Lonidier, The Complete Works of Pat Parker, and Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker 1974 – 1989. Enszer edits and publishes Sinister Wisdom, a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal. You can read more of her work at www.JulieREnszer.com.