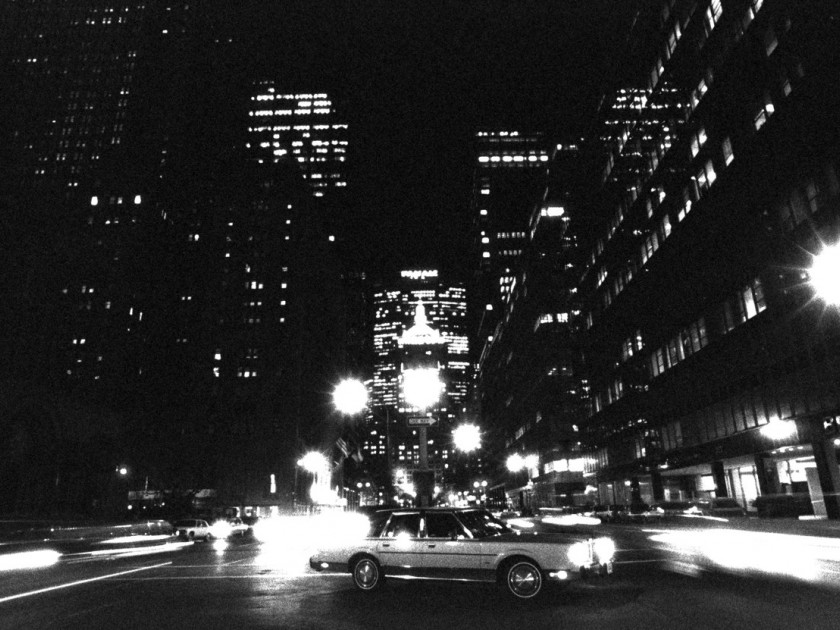

Helmsley Building, Park Avenue, New York, night, 1989, photo by Sérgio Valle Duarte

Like his Pulitzer-nominated album and all the days were purple, composer Alex Weiser’s new song cycle, in a dark blue night, comprises Yiddish poetry set to music. It’s inspired by Weiser’s work at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (which is where I met him, years ago). And like his first album, in a dark blue night is striking, its beauty stemming from surprising harmonies and juxtapositions. The world of sound Weiser creates is as vast as the New York City skyline — a prominent theme in in a dark blue night.

Miranda Cooper: This is your second song cycle of Yiddish poetry set to music. As you know, I am smitten with your work, especially and all the days were purple … I even have the album art framed. After the success of that album, what led you to compose this song cycle, in a dark blue night?

Alex Weiser: There is so much incredible poetry in Yiddish, I wanted to return to it for further work. Being a lifelong New Yorker, and since New York has been such an important city for Yiddish historically, I was curious to explore it through Yiddish poetry.

MC: How did you go about choosing these poems? What elements did you consider?

AW: I spent a long time scouring books for poems to put together into my own mini-anthology of Yiddish poetry about New York City. I ended up being particularly drawn to depictions of the city at night, which I think show a quieter, more intimate side of the city that people don’t always think of first — they tend to think about the cliché of hustle and bustle.

MC: Could you tell me about the poems you chose?

AW: The cycle opens with a setting of Morris Rosenfeld’s “Ovnt ” (Evening), in which the Hudson river, “lost in thought in its cold silver-bed,” murmurs a lonely good night to the setting sun. In the center, I set Naftali Gross’s “Nyu-york” (New York), which describes the city lights as “like the stars in heaven.” The cycle closes with a setting of Reuben Iceland’s “Nakht-refleks ”(Night Reflex), in which skyscrapers are depicted as man-made wonders that rival the divine.

MC: The video has lovely subtitles in English accompanying all the songs. Were the poems already translated, or did you find them in Yiddish?

AW: I found the poems in Yiddish, and when I made my anthology for myself, I also made my own translations of all of the poems. It was a fun way to get to know them really well and think about all of the poets’ choices. For the subtitles in the video, I refined those initial translations a bit.

MC: In my own experience, the work of translation definitely allows you to access a poem on a different level. I can imagine that some of those insights — into an author’s word choice, rhyme scheme, syntax, et cetera — could provide a wealth of inspiration for musical composition.

AW: Yes, exactly. The act of translation really jump-starts the kind of close reading that I find necessary for setting a poem to music.

Being a lifelong New Yorker, and since New York has been such an important city for Yiddish historically, I was curious to explore it through Yiddish poetry.

MC: How do you view the relationship between the music and the poetry? Do you feel that you’re putting them in conversation with one another? Or writing the music to express the poetry in a different medium? Something else?

AW: Whenever I’m setting a poem to music, I try to build off of the poem’s imagery and ideas in the music. In the first song, for example, I read the poem as a kind of lullaby that the Hudson is singing to the sun, so I built off that idea with a kind of cradle-rocking musical motif and a simple, folk-like melody.

MC: First you had purple days, now a blue night … next should we expect a green dawn? Are you planning a song cycle based on the Yiddish film Grine felder? Or is this just a coincidence?

AW: It’s actually totally a coincidence, but I love the connection. Perhaps it points to some of the kinds of things that jump out at me in poetry.

MC: They’re very visually evocative titles — it seems to me that there would immediately be a visual aesthetic in the mind’s eye when listening to these songs. Is that intentional?

AW: Yes, I think I’m drawn to particularly imagistic poetry. I find these kinds of evocative images musically inspiring and also helpful as an entryway into the sound world of a piece.

MC: Can you tell me a little bit about the experience of finding out you were a Pulitzer finalist?

AW: It was completely unexpected — a welcome surprise! I was in between meetings and got a call from one of my best, old composer friends. I wasn’t sure if I should answer at first because I only had a few minutes, but I figured I’d just say hello briefly and — then he told me he’d heard that I was a finalist for the Pulitzer prize. I didn’t believe it at first, but pretty soon I was inundated with texts, calls, emails, and messages, and I realized it was real. I didn’t get any kind of official notice from the Pulitzer committee until some time later.

MC: Amazing. So what’s next?

AW: I loved working on this cycle and I’d actually like to add more songs to it. I’m currently working on two more songs that fit alongside the three here, setting additional poems by Anna Margolin and Celia Dropkin. I’m hoping to use this expanded version of the song cycle as the basis for my next album.MC: I look forward to hearing it. A sheynem dank, Avreml!

AW: Nishto farvos, Mirele! Zayt mir gezunt un shtark!

This piece is a part of the Berru Poetry Series, which supports Jewish poetry and poets on PB Daily. JBC also awards the Berru Poetry Award in memory of Ruth and Bernie Weinflash as a part of the National Jewish Book Awards. Click here to see the 2020 winner of the prize. If you’re interested in participating in the series, please check out the guidelines here.

Miranda Cooper is a NYC-based writer, editor, and literary translator. Her literary criticism, essays, and translations of Yiddish fiction and poetry have appeared in a number of publications including Jewish Currents, Kirkus Reviews, the Los Angeles Review, Pakn Treger, and more. In 2019, she was named an Emerging Critic by the National Book Critics Circle. She is also an editor at In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies.