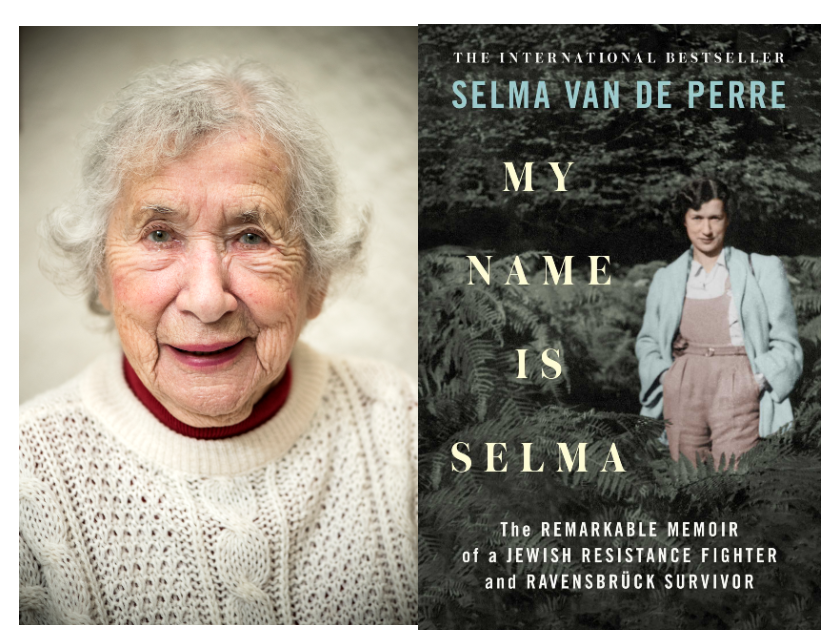

Headshot by Chris Van Houts

Selma van de Perre’s powerful story My Name Is Selma: The Remarkable Memoir of a Jewish Resistance Fighter Ravensbrück Survivor topped the bestseller lists for weeks in the Netherlands and is out on May 11th in the US. She spoke with Marc Katz on the decision to share her story, her experiences in the resistance, and her relationship to Amsterdam today.

Marc Katz: What made you tell your story now? What about this moment felt right for talking about your experience during the Shoah?

Selma van de Perre: I was very busy building up my life. I took over my husband’s journalist job after his death in 1979. For relaxation, I started a painting class. So many books had been written by victims of the Holocaust that mine was not needed. One day I told the teacher I could not come next week because I was going to Holland. “Have a nice holiday,” she said. I told them it was no holiday; I had to lay the wreath at the ceremony in Amsterdam. They asked details and I told them about the resistance. They had never heard of resistance in Holland nor about concentration camps for non-Jews. I decided then that I had to write a book about it. It was only when I learnt that people in England did not know that there were concentration camps all over Europe where non-Jewish resistance fighters were also imprisoned and killed. By then, in the 80s, they knew about Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz and resistance in France and some knew about Arnhem.

My nephews and friends told me to write my story down — “You are the last of the generation.”

So I started to make notes. But I had no time during the day when I worked, and could not write in the evening, otherwise I would not sleep.

Friends kept asking how the book was going and I had to say not very much. Finally, in about 2004 I started to write. But my first foolscap page was in 2013, and it took to 2017 to get it finished. I did not think it would be any good to publish. I was very surprised when it went so well and became top of the bestsellers list for weeks.

MC: One of the things that make your story unique is how you were able to pass as a non-Jew and still work in the resistance. Why did you decide to fight rather than hide?

SVDP: I often thought of it after the war. I never thought of fleeing or of not doing the resistance work. It was needed to save lives. I also saw many non-Jewish people helping so I thought it necessary. I was young and active and capable to help.

MC: You had so many close calls, both during your work in the resistance and when you went into Ravensbrück. When were you the most scared?

SVDP: There were several. In the beginning, I was not used to the checkups. I think I was very scared when I had to open the suitcase with illegal papers on the Leiden station. Also when the chap called out my name, Selma, in Leiden. And of course in Paris. And I was also scared when I lost the suitcase in Leiden and the German told me to get out of the train.

I was also scared when I sat in the Gestapo headquarters in the Euterpe straat in Amsterdam.

They had never heard of resistance in Holland nor about concentration camps for non-Jews. I decided then that I had to write a book about it.

MC: Although you were Jewish, you ended up in Ravensbrück because of your resistance activities. What did it mean to you to know that you were treated differently because you were able to hide your Jewishness?

SVDP: I was treated like all the other non-Jewish women. I had pushed my Jewish identity away.

MC: Tell us a little about your father’s fountain pen. Why did you decide to keep it with you throughout your time in the camps?

SVDP: A resistance friend had smuggled the pen in a thermometer holder (she was a nurse) and it was easy to hide. I felt my father near me. It felt terrible to lose it.

MC: When you were working in the factory, you were offered pay. You gathered everyone together and declined. Tell us about the decision to stand up to the Germans in that way.

SVDP: It was forced work so I felt we must refuse pay for it.

MC: You have a very powerful passage in the middle of your book:

“I had a strong feeling that I wanted to survive — it’s an instinct that is part of my character and has been with me my entire life — but for that to happen I know you had to have hope. If you gave up hope you could sink into a depression and your chances of survival would disappear.”

Tell us a little bit about how you kept up your hope.

SVDP: I used to say I had luck. But a German friend (non-Jewish and born after the war) said, “No Selma it was not luck, you knew what you did. You said no and yes at the right time and turned around when necessary. Call it instinct, but that is what you did.” And she was probably right.

And I knew I wanted to survive; I did not want the Germans to have the satisfaction of getting me dead. And friends were very important. My Czech friend Valy used to say to me “Don’t give up Marga,” and she brought me some food.

MC: As your story shows, there were good people in the Netherlands, but it was also one of the most dangerous countries in Europe for Jews. Tell us about your relationship with Amsterdam.

SVDP: Although many people worked in the resistance, and many non-Jews lost their lives because they were hiding Jews, many other Christians betrayed Jews or resistance fighters in hiding just for money. They got 7 guilders for every Jewish person they betrayed.

Amsterdam was completely changed in 1945 after the war without the Jewish population. Artists, singers, comedians, shopkeepers and more had mostly disappeared.

Rabbi Marc Katz is the Rabbi at Temple Ner Tamid in Bloomfield, NJ. He is author of the books Yochanan’s Gamble: Judaism’s Pragmatic Approach to Life (JPS) chosen as a finalist for the PROSE award and The Heart of Loneliness: How Jewish Wisdom Can Help You Cope and Find Comfort (Turner Publishing) which was chosen as a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award.