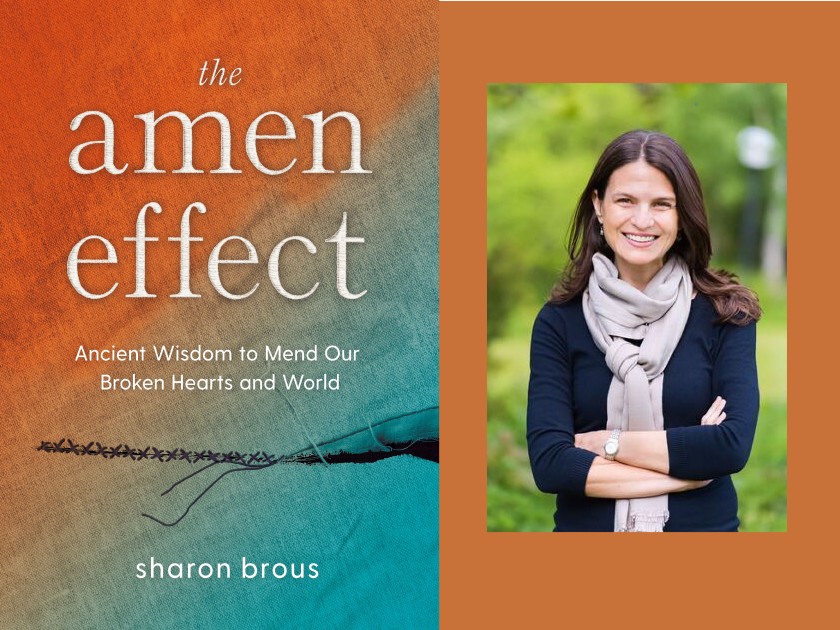

Isadora Kianovsky speaks with Rabbi Sharon Brous about her new book The Amen Effect. They delve into the process of compiling and creating this powerful book, and its important resonances for our contemporary Jewish world.

Isadora Kianovsky: What inspired you to translate your sermons into a book for the wider public? Could you talk about your process of doing so, and if/how the form and approach of the book might differ from that of the sermons?

Sharon Brous: The sermon is a deeply emotional and powerful tool for connecting the teacher/preacher and community, for inviting people to access ideas simultaneously through the head and also the heart. A good sermon makes us cry and sometimes laugh, teaches us something we didn’t know before, helps us see something we did know before in a new way, activates, engages, sometimes enrages, always inspires. It enters us into dialogue with generations of people who came before us and struggled with these same texts and ideas but through different lenses. It marries new, different, or unexpected reads of traditional texts with stories that open the heart and make us want to live differently.

When I gave a sermon called “The Amen Effect” at IKAR years ago, something powerful, wonderful, and mysterious happened. It changed us, as a community. I could feel it. Since then, whenever I’ve shared the idea in talks in other communities, I can feel its resonance. People often gasp or tear up when I even just share the main idea, drawn directly from a (fairly obscure) Mishnah. It helps them feel seen. Less lonely. Less helpless. More hopeful.

Even still, the sermon is a limited format for engagement. The rabbi/pastor has many twelve minutes, maybe thirty — not more — to inspire. For years I wondered what a deep dive would look like into this core idea. What might I learn, and be able to share, if I let this sermon breathe, if I gave it 50,000 words, rather than 5,000?

In the end, the book reads like a series of sermons, with stories, texts, and studies. But these are all woven together into one super-sermon, a book that can be read over time, or even in one sitting.

IK: How do you think your book fits into the current moment, both Jewishly and on a universal scale?

SB: I wrote this book for another world. I spent two decades wrestling with the question of how we heal, individually and collectively, in a time of loneliness, social alienation, and so much division. I wanted to share some of what I have learned building and pastoring to IKAR, some of the powerful lessons about love and loss, community and connection.

But when I closed the manuscript a year ago, I really could not have imagined the reality we find ourselves in, as the book launches in a post-October 7 world. In November, I stepped into the sound booth to record the book with great trepidation. To my great relief, I found that the message not only holds up, but actually feels more relevant now than at the time when I wrote it. After all, the power of rooting oneself in ancient wisdom is that it really does stand the test of time.

IK: Which sermon was most challenging for you to write, and why?

SB: The words of this book poured out of me. The most challenging part was putting the pieces together in a way that would have both emotional, spiritual, and intellectual heft. I wanted to surprise, inspire, and offer something new. I probably spent the most time on chapter two, the chapter on loneliness. There is so much great literature on loneliness now, and I wanted to make sure that what I’d bring would be additive and not repetitive.

The sermon is a deeply emotional and powerful tool for connecting the teacher/preacher and community, for inviting people to access ideas simultaneously through the head and also the heart.

IK: On Ezra Klein’s podcast, you mention a group of Palestinians and Israelis that focuses on “the idea…that if we are going to live as neighbors, we have to learn how to share our grief so that we can collectively build a shared society and a shared future.” How do you hope your sermons and book add to this conversation and the hope of a collective future?

SB: In the final chapter, I explain that the lion’s share of the book is an argument that openhearted, authentic human connection is a spiritual and biological necessity; it is the key to belonging and the antidote to loneliness; it can be the deepest expression of faith, honoring the image of God; it gives our lives purpose and meaning; it helps us approach moments of joy and pain authentically; it helps both the wounded and the healers; it won’t save us, but matters profoundly nonetheless. But what happens when encountering the other is more than inconvenient, uncomfortable, or even destabilizing, but actually treacherous, even dangerous? What happens when another person’s presence not only repels us, but renders us unsafe? When is it right to withdraw from a relationship, to fortify oneself rather than open up?

It is here that I explore the boundaries of engagement, and how the Jewish tradition pushes us to engage with curiosity and empathy toward almost everyone. This, of all the messages, will be the hardest and most important in our current climate. We are traumatized and full of sorrow. We are completely torn apart — perhaps more now than ever. I fully understand why it might feel impossible to find our way to one another, to stitch back together the frayed edges of our broken hearts and our society. I get why good people retreat and entrench in times like these.

But I know that healing is possible. The reality is, the only way forward is together. I hear the tradition calling us to curiosity. Emotional agility. Wonder. Imagination. We must find our way to one another’s humanity, and then together, imagine a different kind of future.

IK: What are you reading right now?

SB: I just finished an advanced copy of my friend, Brian McLaren’s astonishingly powerful book, Life After Doom, about the climate crisis and the urgent need to harness our resiliency for a kind of devastation that looks increasingly inevitable. I deeply appreciate the way that McLaren speaks hard truths — less as an activist, wielding a cudgel, and more as a pastor, with his own broken and still hopeful heart. Without blame, but with shared responsibility. With honesty, and also with tender love and care.

Isadora Kianovsky (she/her) is the Membership & Engagement Associate at Jewish Book Council. She graduated from Smith College in 2023 with a B.A. in Jewish Studies and a minor in History. Prior to working at JBC, she focused on Gender and Sexuality Studies through a Jewish lens with internships at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute and the Jewish Women’s Archive. Isadora has also studied abroad a few times, traveling to Spain, Israel, Poland, and Lithuania to study Jewish history, literature, and a bit of Yiddish language.