Left: Charlotte Salomon self-portrait, 1940, gouache on cardboard

Right: Charlotte Salomon painting in the garden at Villa L’Ermitage, Villefranche-sur-Mer, 1939

Collection Jewish Museum, Amsterdam © Charlotte Salomon Foundation

What’s a biographer to do when the Holocaust has wiped out letters, diaries, photos, and the individuals who created them? Who is left to speak to these lives?

When I was researching German Jewish artist and writer Charlotte Salomon (1917−1943) for what would become It’s My Whole Life: Charlotte Salomon: An Artist in Hiding during World War II, I first looked for surviving Salomon family members who might be able to shed light on Charlotte’s life. Perhaps a descendant of one of Charlotte’s cousins on her father’s side? Or someone from her husband’s family, or maybe someone on her stepmother’s side? But when I began researching for this project there were no longer any living relatives, because of age and the Holocaust.

I built a family tree for Charlotte, researching as deeply as possible to try and identify potential living descendants. I did make some useful discoveries, though they weren’t what I was looking for in terms of descendants. Instead, I found evidence that Charlotte was related to the German impressionist painter Max Liebermann (1847−1935) through a marriage tangle in her maternal grandmother’s family. I’d seen hints about this in two sources, but it was validating to finally stare at the marriage connections in front of me.

Charlotte was around eighteen when Liebermann died at age eighty-eight. It would have been easy to assume that they had met at family gatherings and that she was familiar with his art, but I could find nothing concrete to substantiate this. Yes, he had been a guest in the Salomon home in Berlin, along with Albert Einstein, Käthe Kollwitz, Albert Schweitzer, and many others. And yes, Charlotte’s stepmother, opera singer Paula Salomon-Lindberg, had sung Robert Schumann’s Talismane (lyrics by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe) at Liebermann’s funeral, as requested by Liebermann in his will. The song itself had clearly made an impression on Charlotte because a recording of Paula performing it was one of the few possessions that Charlotte had taken with her when her parents sent her to the south of France after Kristallnacht.

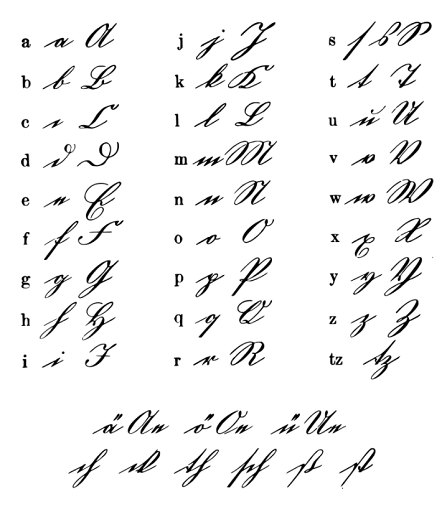

I used German birth, death, and marriage certificates frequently in my research, in order to create family trees. This also meant having to tackle Kurrentschrift, the old-style handwriting from the late medieval period that was still used on official German documents until the early twentieth century. Oddly, this is where sports helped. Tennis friend and German translator Gracie Schild explained Kurrentschrift to me and armed me with a cheat sheet to help decipher this handwriting letter by letter, including upper- and lower-case variations, and German ligatures like sch, th, sz, and so on. Because the original documents had consistent, repetitive categories — birth, death, religion — I quickly got the hang of it, apart from the annoying instances of sloppy penmanship where nothing was legible.

Kurrentschrift cheat sheet

After failing to come up with family descendants for Charlotte, I decided to make family trees for people close to her to see if there might be living descendants amongst them. I did this for many people, including Charlotte’s friend in Nice, Emil Straus; her French doctor Georges Moridis who hid Charlotte’s paintings and writings at his home in the south of France during the war; her close friend and benefactor Ottilie Moore, who sheltered Charlotte and her maternal grandparents at her French villa in the early years of World War II. I hoped that hunting for their offspring might be more fruitful.

I struck out almost immediately with Emil Straus, even though Straus had a distinguished political career after the war in Germany. I found no evidence that either of Straus’s now-deceased twin sons had families.

Finding George and Odette Moridis’s daughter Kika was much easier. Kika was born early in the war, and I could imagine Charlotte holding baby Kika and playing with her on visits to the Moridis home. I had seen quoted material and photos of Kika in online articles and it was clear that she was a supportive voice for Charlotte’s story and for her own father’s crucial role in Charlotte’s life. Not only did he hide her art, keeping it safe for the rest of us, but he also encouraged her to paint during difficult periods of family strife and wartime terror.

I could easily imagine Charlotte in that office, sometime in the summer of 1940. She and her grandfather had just returned from possible incarceration at the Gurs internment camp in the Pyrenees. Charlotte was depressed and traumatized. She trusted Dr. Moridis as he told her that she should paint with all her heart.

I reached out to Kika. She quickly and deftly fielded my email questions, offering family photographs, and becoming a source for many details about her parents, including the cellar where her father hid Charlotte’s paintings, and the family home where Kika still lives. Her father’s office remains as it was when Charlotte visited. I could not have asked for a more enthusiastic champion for giving voice to Charlotte’s story and aiding me in my research.

This was equally true for Ottilie Gobel Moore’s grand-niece, filmmaker and university professor Dana Plays, who works passionately and tirelessly to tell the stories of Ottilie Moore, Ottilie’s father Adolf Gobel, and Charlotte Salomon through art films that are sensitive to these individuals’ lives and creativity. Dana knew how Ottilie’s personal stationery was designed and had beautiful, detailed interior photographs of Ottilie’s French villa with Charlotte’s paintings hanging on the dining room walls and even knew the correct names of the outbuildings on Ottilie’s property.

Dana also sent a photo of the villa’s living room with its spectacular grand piano. We know Charlotte was very musical. In her painted memoir Life? or Theater?, she even included a musical soundtrack. She heard music in her head when she painted, and she wanted the reader to have a similar experience. She used painted capital letters to add song titles or lyrics to her paintings. Perhaps twenty-two-year-old Charlotte played some of these tunes on Ottilie’s piano.

Both women, Kika in France and Dana in Florida, were gracious, generous, and care deeply about helping to amplify Charlotte Salomon’s story. With collaborative efforts like these that inform books like It’s My Whole Life, I know that Charlotte’s story and art will live on for generations to come.

Charlotte practices for her art school entrance exam, gouache on paper, c. 1940 – 1942.

Collection Jewish Museum, Amsterdam © Charlotte Salomon Foundation

A graduate of The Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey and of the University of New Mexico, Susan Wider has written for Orion, THE Magazine, The Fourth River, and Wild Hope magazine, among others. Before becoming a full-time writer, she held senior management positions at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, The Santa Fe Institute, and the Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute. Earlier in her career she taught American English for the French Chamber of Commerce in Normandy, France and worked as a violinist in several professional chamber and symphony orchestras. It’s My Whole Life is her first book. She lives outside Santa Fe, New Mexico.