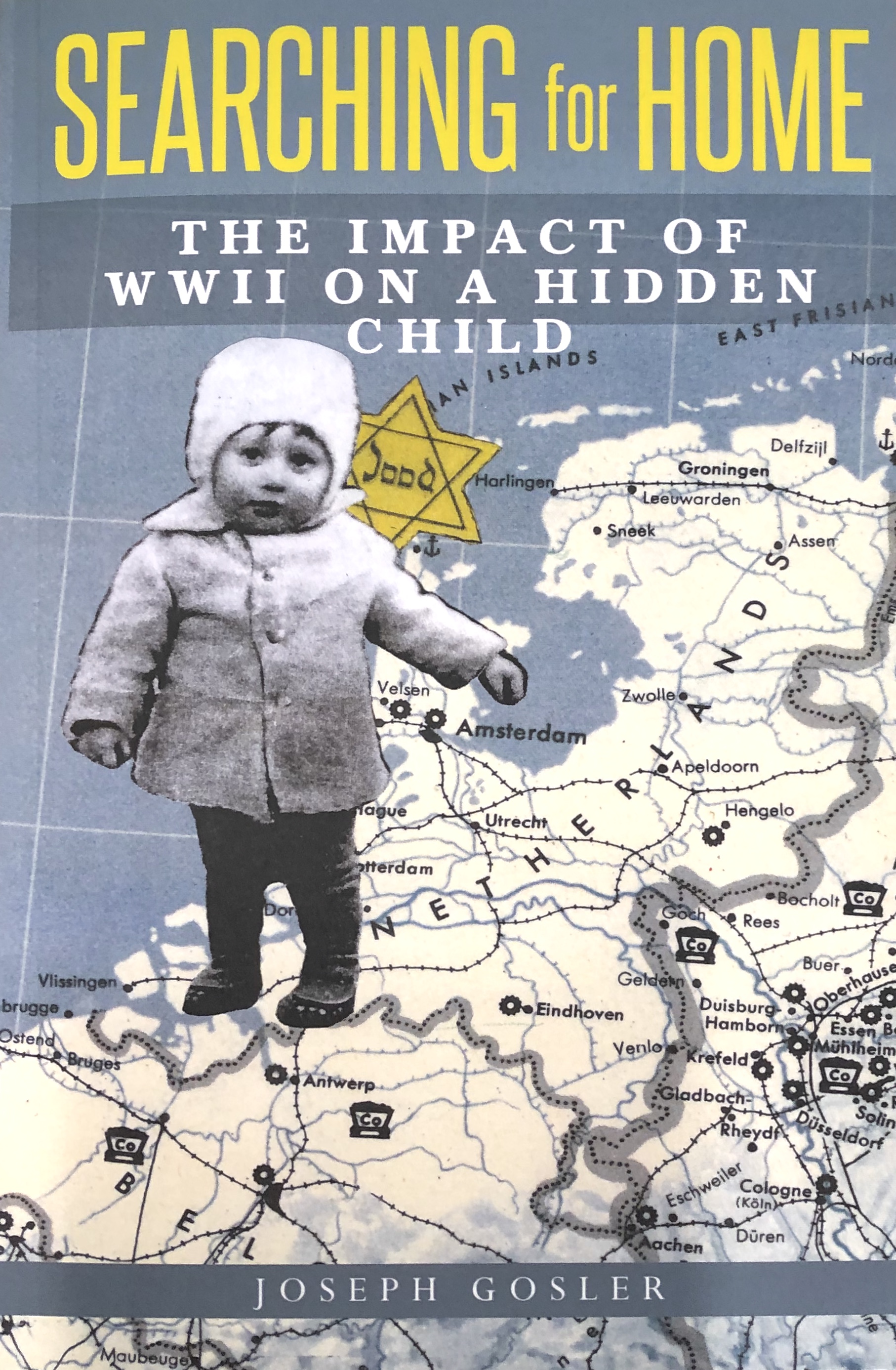

I was born on July 27th, 1942, to Henriette Swartberg-Gosler and Maurice Gosler in the provincial capital of Groningen (The Netherlands). My mother tells me the day I was born was a Monday morning, not really distinguished by anything unusual except for the British bombers flying overhead. My birth certificate notes the birth name of Joseph Gosler, but my name would change several times during and after WWII. Every new name of mine represented a layer or portion of my life, ever connected like the canals that crisscrossed my birth city of Groningen. Each experience and identity melded into the person I am today.

In retrospect, it seems strange to have a child during wartime, but I believe the Dutch, including my parents, were determined to hold on to a sense of normalcy, even if it was out of desperation. It could also have been a form of unintended personal resistance to have a child, in contrast to the Nazi nightly raids which surgically removed whole families, or sometimes just the grandparents. That was the paradox of life in Holland, at least through 1942, and since I never heard otherwise, I must assume that my parents felt secure enough to have me.

On the surface, my birth and infancy were no different than any other young child’s except that I was Jewish. At my birth, my father Maurice, was already imprisoned in a forced labor camp near Kloosterveen, where he worked 16 hour days and could only imagine what his young son looked like. To share the experience of my birth, my mother sent a letter to the camp, stating that she was ill and asked if there was a way for Maurice to come to her. Although the Nazi stranglehold on everyday life was becoming crystal clear, here was an example of the schizophrenia of wartime Holland, because my father was given a three-day pass.

After the three days, my father was ready to return to the camp, but my mother noticed that there was no return date stamped on his pass. They argued vociferously about the error. My father, ever true to his word, had every intention of returning to the camp, until my mother convinced him otherwise. My father’s typically Dutch sense of civic duty, evident through every strata of society, would have cost him his life. Worrying that the camp’s administration would find the omission, my parents and my widowed maternal grandmother, Martha, left Groningen and travelled to Amsterdam.

The Jordaan or Jodenbuurt (Jewish neighborhood) of Amsterdam was still a thriving quarter of nearly 80,000 Jews. Many families could trace their Amsterdam roots back four centuries. The Nazis had effectively turned the Jewish sector into a ghetto, forcing various restrictions on movement for both day and night. It was October, 1942, and though life was more sobering, we found a place to live and my father took on day labor. However, it became depressingly clear to my parents that they needed to remain mobile and flexible and that I undermined that possibility.

The Jordaan or Jodenbuurt (Jewish neighborhood) of Amsterdam was still a thriving quarter of nearly 80,000 Jews. Many families could trace their Amsterdam roots back four centuries.

Much later in my life my parents told me their feelings of being in a state of controlled fear and numbness. Full of remorse and yet relieved, they hoped I would be safe, like Moses drifting in the reeds, there was no guarantee they would ever see me again.

Within months thereafter, my parents and grandma decided to travel to Gelderland, an agricultural province southeast of Amsterdam. They hoped to work and hide on one of the many small farms that dotted the fertile plains like tiny white mushrooms. Each day, they travelled at dawn, carrying valises filled with their meager belongings. One night, while sleeping in a small barn, my mother woke up convinced that their host had informed on them. The gut feeling meant they had to leave immediately. Needing more time to rest, my grandma resisted and stated she would meet them later in the day. They never saw her again, and later learned she was taken by the SS, deported and murdered at Sobibor. When I was much older, I became painfully aware, as had my parents, that instinct and timing spelled the difference between life and death, and, ironically, that we were born under lucky stars.

When I was much older, I became painfully aware, as had my parents, that instinct and timing spelled the difference between life and death, and, ironically, that we were born under lucky stars.

My journey was gentle as compared to my parents and grandma. I was placed with Menier and Mevrouw Dijkstra, a Christian family in Wageningen, a small city near the Rhine River, and by coincidence also in Gelderland. My war time family consisted of “Vader”, a landscape architect, “Moeder”, a housewife, and two daughters, Anneke and Folie, who were fourteen and eleven years old respectively. Both girls had straight blond hair and blue eyes, in contrast to my wavy dark hair and hazel-green eyes. Not long after, I was added to their family register and was called Peter Dijkstra, or Pietje. Safe and content with the only family I knew, I cannot remember whether I missed my mother, or the familiarity of my parents’ home, or the warmth of my mother’s breast or the smell of her skin, but my childhood with the Dijkstras was as wholesome as wartime would allow. Some neighbors assumed I was Jewish and this awareness frightened Moeder and Vader, and they constantly reminded their daughters not to reveal my story.

One day, while playing with other young children in the street, a platoon of Nazi soldiers and tanks, rolled by. The other children scampered to the sides, but whether numb, curious, dumb or defiant, I remained entrenched. The other children motioned for me to move, but I didn’t. Miraculously, the troops divided into two streams as they passed me by. These were dangerous times, but from my two-year-old eyes it was part of my everyday life. I recall another, even more horrifying event, for Vader, when I went to the barbershop for the first time. I saw my soft curls falling to the ground, it startled me and I began to cry, but then I heard and smelled the diesel fed trucks, the rolling tanks and the rhythmic thud of leather boots, and everyone in the shop turned to the window, “Rotmoffen!”, I screamed. A multitude of hands cupped my mouth and whisked me to the back of the store, until the parade of Nazi helmets and boots went by. Yelling rotten Nazis, even by a child, was grounds for certain murder.

By mid 1944, the harsh Russian winter and the Red Army halted the Nazi advance in the East, while in the West, occupied Holland, suffered extreme food shortages and nightly Canadian bombing raids. During those evenings, we went down to the cellar and I sat quietly on Moeder’s lap, while Anneke and Folie sat between her and Vader. We wore extra layers of clothing to ward off the damp cold, and a single flickering bulb bathed us in light. Vader or Anneke would read books to us, songs were sung, and the collective hum of airplane engines overhead blended to create white noise that lulled me to sleep.

In the beginning of Spring, 1945, in the south of Holland, near Maastricht, the fighting ceased and the people were free to walk the streets. A couple of months later the rest of Holland was freed. It was a period of euphoria, hysteria, hate and vengeance. These were frantic times, made more so, because it took my parents another six weeks to find me.

Three years had passed. The infant they remembered had not only changed physically, but had wrapped himself, emotionally and psychologically, in the arms of the Dijkstra family. My parents were strangers, I did not recognize them and I wanted to return to my “real” parents. We were together again, but each member was forever damaged by the experience of war. For my parents, each day bled into the next, splattered with painful memories. They were in an endless state of mourning.

As for me, I was still wrapped, tightly, in my own innocence, but cracks were beginning to form on my porcelain psyche. Although reunited with my real parents, I felt abandoned by the only family I knew. I cried for Moeder. I was angry, anxious, distant and confused. I trusted no one.

Joseph Gosler was born in Groningen, theNetherlands during WWII and after the war he emigrated to Israel with his family and subsequently to the United States, where he has lived since. His life’s journey has been a circuitous one and as a result he has often meandered off the main road. This is best exemplified by the 20 plus years it took him to achieve his BA in History and MBA in corporate finance through the City University of New York.

For nearly 40 years he has worked in educational settings ranging from day care centers to private schools in the capacity of Business Manager. He and his wife founded a pre-school called Beginnings Nursery, have one son and live in New York City. Mr. Gosler retired from Friends Seminary in 2004, and today is actively involved in several Quaker projects, writing, gardening, traveling and walking his dog. “Searching for Home”, describing his life as a Hidden Child, is his international debut.