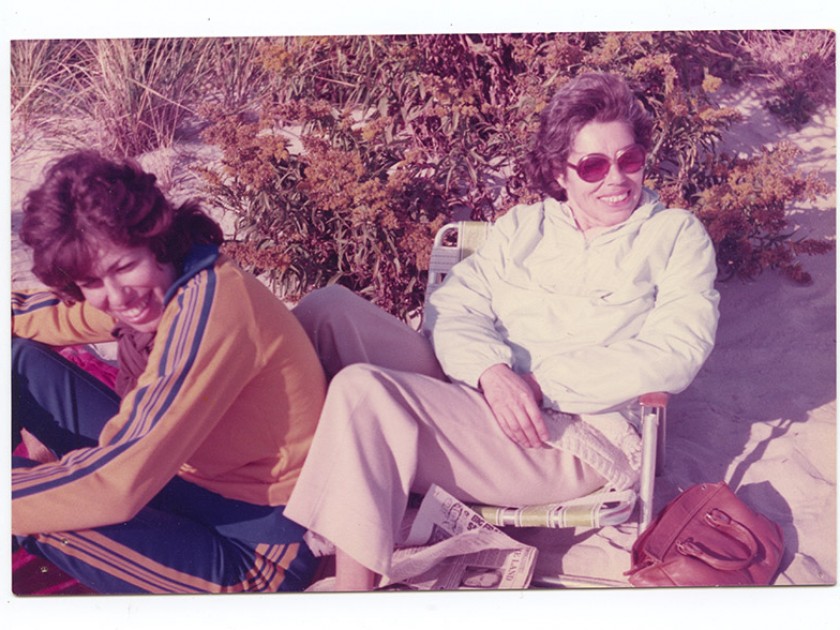

Image courtesy of the author.

The email that sparked the idea of publishing my mother’s memoir came from a man in Berlin. He wrote:

Dear Helen,

A friend of mine in Prague just read the Czech translation of your book Where She Came From in which you mention your mother having a discourse in a prison cell

with Marianne, my father’s first wife. As your description appears to be based on some kind of facts that you have, I would really be interested to learn the source.”

I’ve been receiving personal mail from readers since I wrote about children of Holocaust survivors in a 1977 issue of the New York Times Magazine. Most of the feedback is appreciative; some inquiring, some angry, but no one had ever suggested that my journalism was “based on some kind of facts.” I dug into my files and found “the source” – three pages of an unpublished typescript that my mother had written in New York in the early 1970s. They described her arrest by the Gestapo in June of 1939 when she was 19 and a young fashion designer in Prague. My mother described Marianne as an older female prisoner who advised her on how to deal with interrogation. I scanned the pages, and emailed them to the man in Berlin. He sent back a glamorous photo of Marianne Golz and, intrigued, I reread my mother’s memoir.

Franci had never aspired to be an author but this was — at the very least — her fourth iteration of her Holocaust experience. She wrote the first while a prisoner in a Nazi slave labor camp in 1944, where she stole a notebook and kept a diary in the form of letters to her mother. After a guard discovered it, the camp Kommandant made her burn it page by page, in his stove. In New York City in 1955, Franci told her experiences to a psychoanalyst. In 1974, I interviewed her for the American Jewish Committee’s collection of Holocaust survivor audio testimonies, now archived at the New York Public Library. Her narrative was, by then, well thought-through.

Franci had never aspired to be an author but this was — at the very least — her fourth iteration of her Holocaust experience.

She had typed her account in English on thin onion-skin paper with the title Roundtrip, a sardonic reference to her journey to and from Prague with a group of Czech Jewish women during the Second World War. It began with her deportation in the fall of 1942 to the Terezin ghetto. From there, she was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, and subsequently to work camps in Hamburg and Bergen Belsen. Ill with typhus, she was taken to a British Army hospital in Celle, Germany. Ultimately, she returned to Prague in the fall of 1945.

Franci’s war was a world centered around girls and women. She had been running a fashion salon in Prague in March of 1939, when Hitler invaded. Her mother, Josefa Rabinek, had established it in 1920 and, Franci decided to drop out of her elite high school and study dress design, eventually becoming her mother’s business partner. In 1938, at the age of 18, she became the salon’s proprietor and developed the skills that would repeatedly save her life.

In Terezin, she was quickly recruited to the clothing workshop. My mother’ memoir was filled with specific details that only a meticulous craftsperson would remember: the weather on the day the German Army marched into Prague; how the Nazi who “aryanized” her salon sized up his prospects of profit; how she decided to have a nose job during the Occupation; how she became addicted to cigarettes after she was forcibly separated from her parents in Terezin; how she decided to lie to Dr. Mengele during a selection at Auschwitz and tell him she was an electrician rather than a dress designer; how she nursed her cousin Kitty’s boils in Hamburg by stealing yeast cakes from a German bakery; how her sister prisoners formed alliances, fell in love and/or bartered sex for food with men and women, got pregnant, got sick, died.

…how she decided to lie to Dr. Mengele during a selection at Auschwitz and tell him she was an electrician rather than a dress designer…

My mother died unexpectedly in 1989 of a brain aneurysm, when she was 69 and I was 41. Reading her text nearly 30 years later, I heard her voice again: candid and contemporary. In 1975, that candor might have been the reason no publisher accepted her memoir; by 2018, the world had caught up with my mother. Books and television shows like Orange is the New Black lifted the curtain on relationships between women in prison. In academia, Women’s Studies and Holocaust Studies were delving into the experiences of women in war and queer historians were sifting sources for documents of these experiences. The #MeToo movement was providing a vocabulary for an international conversation about the connections between sex and power.

Thirty years after my mother’s death, my relationship to her had also changed. I was now older than Franci was at the time she died, a mother of two sons, and a grandmother. I was able to take in what I had been unable to understand as a child, adolescent, or even a younger woman. As a journalist, I knew a good narrative when I read one; and as a reader of women’s history, I knew her memoir was unusually rich source material.

Franci and Helen and her brother David Epstein at the apartment house on Riverside Drive in the 1960s.

I had already used some of it as resources in Where She Came From: A Daughter’s Search for Her Mother’s History, a family history of three generations of women in my Czech Jewish family. With the growth of Holocaust and Women’s Studies, several of the people Franci described have become famous.

I asked friends who were academics whether they thought – 75 years after my mother’s liberation from the camps – readers would still be interested in her story. Their answer was an overwhelming yes. Publishers agreed.

I grew up very close to my mother as well as in awe of her, impressed not only by what she had survived but by the lessons she drew from the war. Franci often referred to the concentration camps as her “university,” where she had received a unique education in human behavior. She never stopped mourning those who did not survive, and had not a shred of self-pity. Her greatest concern was that due to human nature, what happened to her could happen again in a different form, to anyone, anywhere in the world.

Helen Epstein (www.helenepstein.com) is a veteran journalist and the author of the non-fiction trilogy Children of the Holocaust, Where She Came From; and The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma.