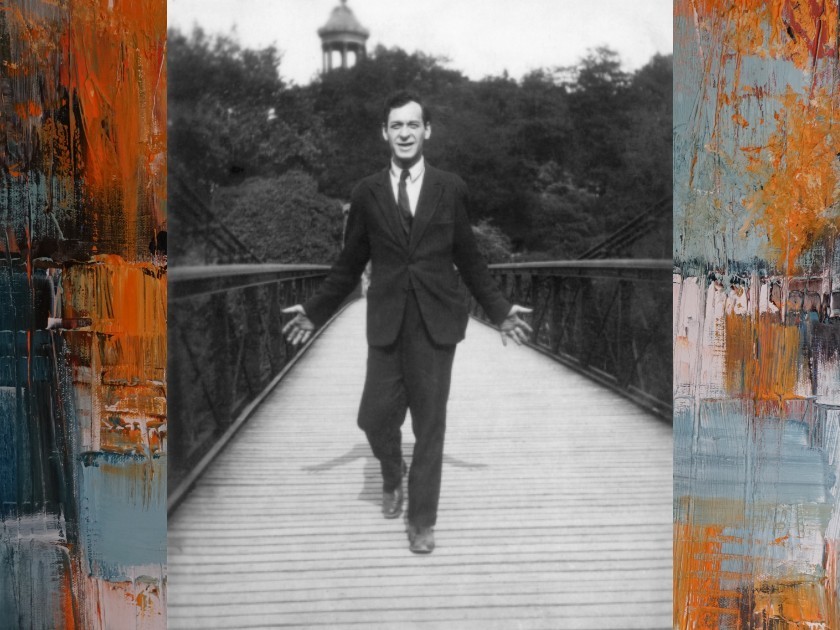

Abraham Mintchine at the Buttes Chaumont in Paris, 1928, image courtesy of the publisher

As a cultural historian, and the son of a German Jewish refugee father, I was drawn in immediately to the resurgence of interest in the fate of Nazi stolen art, which began in the late-1990s. Even so, I was concerned that dwelling on the darkly enthralling story of how Nazis and collaborators ransacked Jewish-owned art collections obscured larger historical questions: How did certain Jews acquire so much great, old and modern art in the first place? How, against all odds, did these outsiders come to play a pivotal role in shaping the modern art world? How did they become the old masters’, new masters, and the modernists champions? And how, finally, did their sudden prominence in a realm previously dominated by non-Jews fuel a furious backlash from antisemites and, then, a violent onslaught from Nazis.

This is the untold story of Nazi stolen art that I set out to tell in Belonging and Betrayal, by focusing on the rise and fall of a small circle of remarkable individuals and families of Jewish origin. What caught, and kept, my imagination, were the fascinating stories surrounding the protagonists’ lives and works.

My feelings and thoughts about the protagonists changed over time. I tried as best I could to sympathize with their situations, if not always their actions; I could not help but respect and admire the remarkable accomplishments of these men and women— many of whom came from very modest backgrounds and had little in the way of formal education— who developed astonishing eyes by scrutinizing countless works of art in museums, galleries, and exhibits.

I offer three character sketches: a collector, a dealer, and an artist.

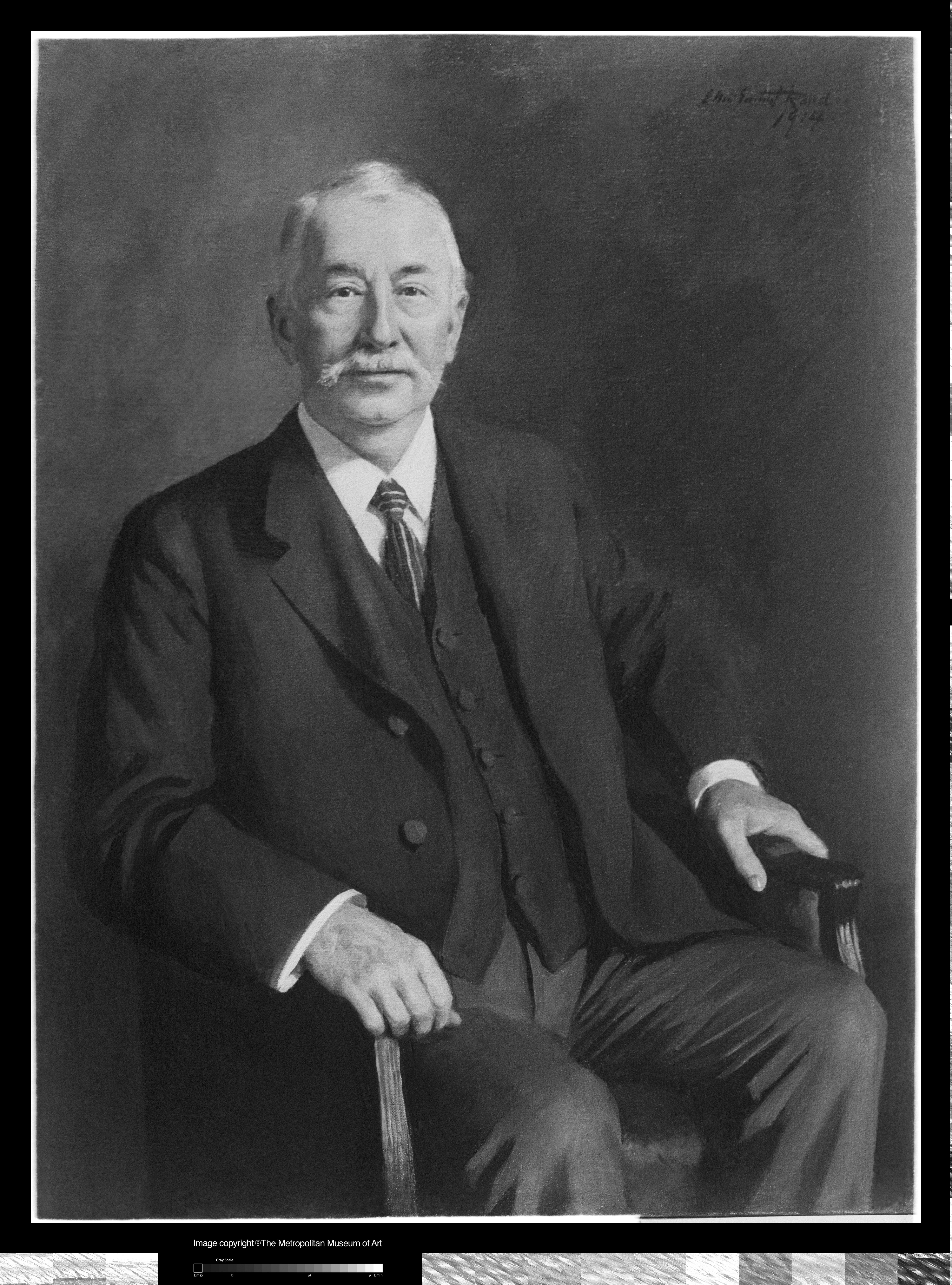

As a child growing up in New York City, I knew B. Altman as one of the metropolis’s leading department stores. I recall going there at least once with my mother when she was shopping for a spring coat. It was only many years later that I came to appreciate the importance of the extraordinary art collection that its founder, Benjamin Altman, had put together. The son of Bavarian Jewish immigrants, Altman took over his father’s very modest dry goods business and turned it into a great emporium. Altman chose the goods he carried with much the same care and scrupulousness that he later put into selecting art objects. Altman was an enlightened employer, who cared deeply for the welfare of the people who worked for him. Altman was not a show-off. What he lacked in bravura, he more than made up for with an unerring eye for quality, and an exceptional gift for organization; both qualities were of great use as he built his art collection, housed in the private museum in his Fifth Avenue mansion. Prudent and deliberate, Altman pondered possible acquisitions and did not take well to being rushed or pushed. This frustrated his principal dealers, Henry and Joseph Duveen, who could not resist urging one picture after another on him.

Starting out with pottery, Altman worked his way toward the Old Masters, including the great Italian, Spanish, and Dutch painters of late the medieval and early modern era. And, though he was particularly drawn to Rembrandt, as were many non-Jewish New York merchants, he wanted to build an encyclopedic collection, which represented different schools and eras. He did just that on the Duveens’ advice. What Altman lacked in formal education he more than made up for in intelligence, effort, and curiosity.

Unlike many art collectors then and now, though, Altman was uninterested in buying art to win social status. A life-long bachelor, Altman belonged to “Our Crowd,” the circle of well-to-do German Jewish families in New York. He rarely showed his art and he kept his distance from the burgeoning Metropolitan Museum of Art, a preserve in which Jews were unwelcome. Toward the end of his life, Altman had to decide what to do with his magnificent art collection. Would he donate it to the Metropolitan, build a private museum, or bequeath it to his family members?

Benjamin Altman, 1914

Léonce Rosenberg, born and bred in Paris, championed the modern, unlike Altman, who favored Old Masters. In looks, temperament, and approach, Léonce and his younger brother Paul, were markedly different. Both were true art lovers, but Paul was by far the more commercial, canny, and cautious. On the other hand, Léonce was idealistic, impulsive, and visionary, a confident risk-taker in his taste and steadfast in his commitments. For a time, the brothers ran the family gallery that their father Alexandre had built. But they could not— or would not— get along. When they parted ways, Paul stayed put in the gallery while Léonce went out on his own.

What would he do next? He drifted for a time and then delved into collecting antiquities. One day he came across a small gallery run by a German Jewish émigré, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. He could not wait to start collecting the Cubist pictures displayed there, and began doing so at a time that more conventional connoisseurs regarded them as indecipherable, not to mention unsellable.

A man in search of a mission, Léonce thought he had found his cause during World War One. While in uniform, he supported Picasso and the Cubists after their regular dealer, Kahnweiler, reluctantly took refuge in Switzerland. With the end of the war in sight, Léonce opened a gallery dedicated to an idea, the Effort Moderne. On Sundays, he hosted gatherings of established and aspiring artists and writers. Additionally, he published a house journal dedicated to avant-garde art.

Léonce Rosenberg’s profound commitment to the art he championed was never in question, however, the financial viability of his gallery was . Despite his commercial and financial position, Léonce was determined to keep his gallery going at all costs. Although he had grown up in the shadow of the Dreyfus Affair, nothing had prepared Léonce (or other French Jews) for the disastrous fall of France in mid-June 1940 and the ensuing German Occupation. Could he keep his dignity and, above all, his family safe in the face of unremitting humiliations, threats, and dangers?

Léonce Rosenberg

Artists abound in Belonging and Betrayal, among them Monet, Pissarro, Degas, Renoir, Liebermann, Van Gogh, Vuillard, Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Klimt, Kokoschka, and Schiele. One of the most intriguing and least known figures is Abraham Mintchine. Russian-born, he was one of a band of Jewish émigré artists who came to Paris in the early decades of the twentieth century in search of artistic education and glory. He was forever chasing his fellow Russian émigré and near contemporary, Chaim Soutine, whose work haunted him . René Gimpel, expert dealer in Old Masters and chronicler of the interwar art world, was so convinced of Mintchine’s genius that he took him under his wing. It would be difficult to exaggerate the depth of Mintchine’s desire to take in what he saw at the Louvre with Gimpel. Despite occasional setbacks, Mintchine continued to make progress as a painter of portraits and cityscapes. As he struggled with ill health and tenuous finances, he endeavored to support his wife and young daughter. All the while, one question remained: would he fulfill the promise that Gimpel saw in him?

One of the most inspiring and moving photographs that I came upon pictured a young, attractive, and smiling Abraham Mintchine crossing a bridge in Paris with his arms wide open in expectation of things to come. For Mintchine, as for so many other Jews in the art world — dealers, collectors, critics, historians, and artists — art was a bridge in more ways than one. It symbolized the prospect of bridging the gap between Jew and non-Jew by finding common ground in culture. The bridge symbolized the profound desire for acceptance and success that animated so many Jews. Even so, neither Abraham Mintchine nor other aspiring Jews knew that what awaited them on the other side of the bridge was betrayal rather than belonging.

Charles Dellheim is professor of history at Boston University. He is the author of The Face of the Past: The Preservation of the Medieval Inheritance in Victorian England and The Disenchanted Isle: Mrs. Thatcher’s Capitalist Revolution.