Judy (back row, fourth from the left) with her middle-school class. Judy’s best friend, Agi Losonczi, is on Judy’s right, and her “camp sister” Edit Feig is sitting in the first row on the left. Debrecen, circa 1940. “Courtesy of The Azrieli Foundation.”

That year, 1944, everybody came: the believers, the atheists, the Orthodox, the agnostics — women of all descriptions and of every background. We were about seven hundred women, jammed into one long barracks. We were all there, remembering our homes and families on this Yom Kippur, the one holiday that had been observed in even the most assimilated homes. We had asked for and received one candle and one siddur from the kapos. Someone lit the candle, and a hush fell over the barracks. I can still see the scene: the woman, sitting with the lit candle, starting to read Kol Nidre, the opening prayer of Yom Kippur.

The kapos gave us only ten minutes while they guarded the two entrances to the barracks to watch out for SS guards who might come around unexpectedly. Practising Judaism or celebrating any Jewish holiday was forbidden in the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. The Nazis knew it would give solace to the prisoners. But this particular year, some of the older women had asked two kapos for permission to do something for the eve of Yom Kippur.

Most of the kapos were brutalized and brutal people, but a few of them remained truly kind. We knew these particular two were approachable. One of the kind kapos was a tall blonde Polish woman, non-Jewish. The other one was a petite red-headed young Jewish woman from Slovakia.

When they had heard that we wanted to do something for Kol Nidre, the red-headed kapo was simply amazed that anyone still wanted to pray in that hellhole of Birkenau.

“You crazy Hungarian Jews,” she exclaimed. “You still believe in this? You still want to do this, and here?”

Many decades later, every time I go to Kol Nidre services, I can’t shake the memory of that sound.

Well, incredibly, we did — in this place where we felt that instead of asking for forgiveness from God, God should be asking for forgiveness from us. We all wanted to gather around the woman with the lit candle and siddur. She began to recite the Kol Nidre very slowly so that we could repeat the words if we wanted to. But we didn’t. Instead, all the women burst out in a cry — in unison. Our prayer was the sound of this incredible cry of hundreds of women. I have never heard, before or since then, such a heart-rending sound. Something was happening to us. It was as if our hearts were bursting.

Even though no one really believed the prayer would change our situation, that God would suddenly intervene — we weren’t that naive — the opportunity to cry out and remember together reminded us of our former lives, alleviating our utter misery even for the shortest while, in some inexplicable way. It seemed to give us comfort.

Even today, many decades later, every time I go to Kol Nidre services, I can’t shake the memory of that sound. This is the Kol Nidre I always remember.

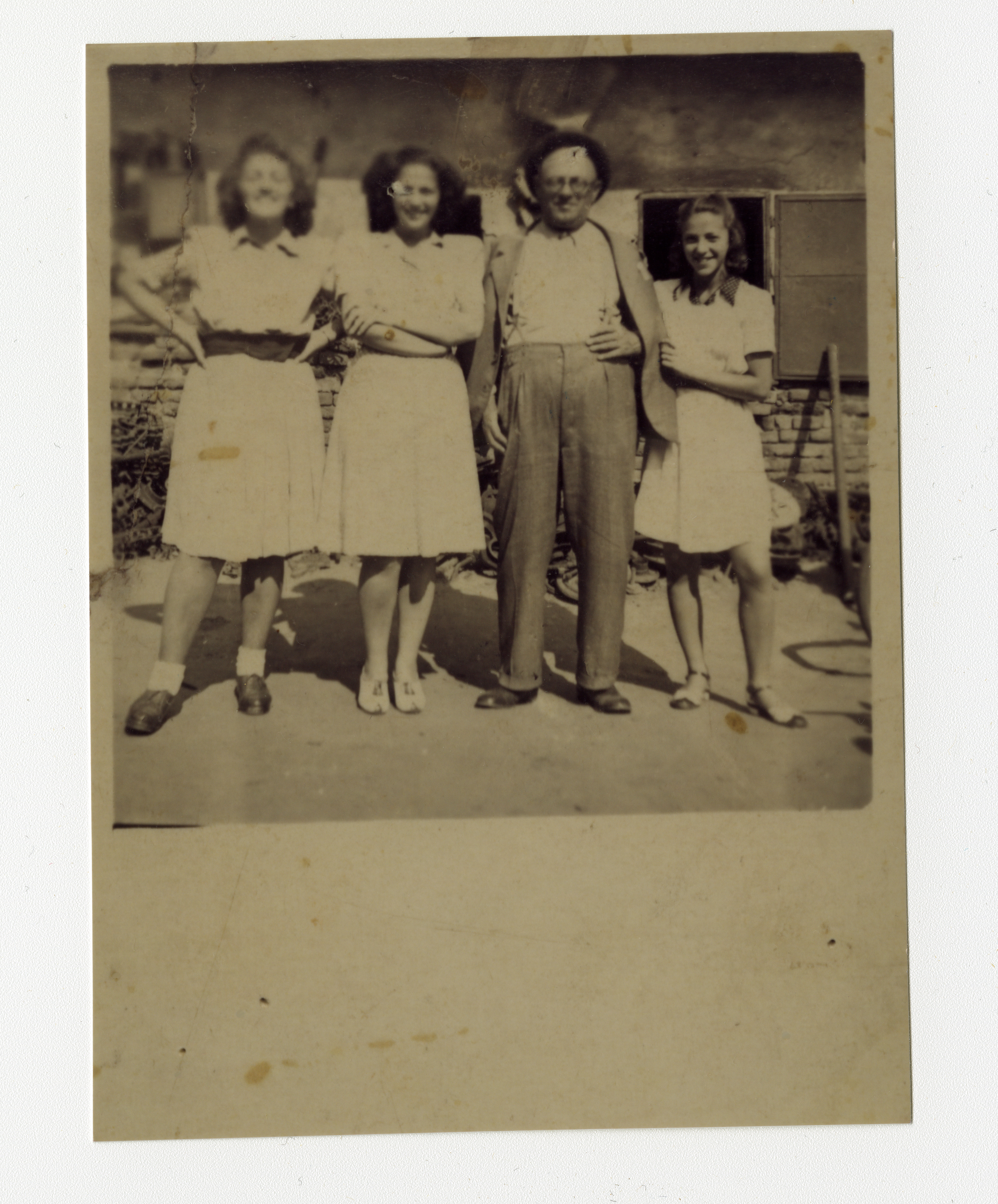

From left to right: Judy’s sisters Évi and Klári; Judy’s father, Sándor; and Judy. Debrecen, circa 1943. “Courtesy of The Azrieli Foundation.”

Judy Weissenberg Cohen was born in Debrecen, Hungary, in 1928. Judy has been a Holocaust and human rights educator since the 1990s. In 2001, she founded the pioneering website Women and the Holocaust, which collects testimony, literature and scholarly material exploring the specific gender-based experiences of women in the Holocaust. In December 2020, Judy Cohen was featured in Dolce Magazine.