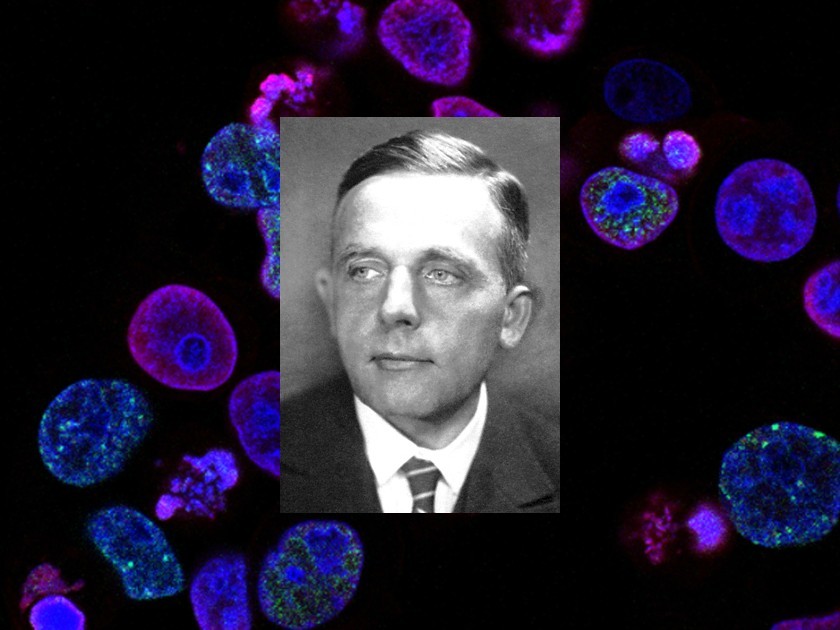

Otto Warburg, 1931

Several years ago, if someone had asked me who counted as Jewish in Nazi Germany, I would have been sure of the answer: anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent. That, after all, is what I was taught in my Jewish day school and in the various Jewish programs I participated in throughout my childhood. However, while working on my new book Ravenous, I was surprised to discover that what I had been taught was not correct. Not exactly.

Ravenous tells the story of Otto Warburg, the famed biochemist who made a breakthrough cancer discovery in 1923. Warburg’s father was Jewish but his mother was not, meaning he had two Jewish grandparents. The Civil Service Law was the first anti-Jewish legislation passed by the Nazis in 1933, and it applied (with some exceptions) to anyone with a single Jewish grandparent. But the passing of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 made things more complicated.

In the original draft of the Nuremberg legislation that banned relations between Jews and those considered “German-blooded,” there was a critical line: “This law only applies to full Jews.” And “full Jews” were defined as someone with three or four Jewish grandparents. Hitler left this mention of “full Jews” in place in the draft of the legislation that was sent to the government press agency. But he removed the line in the draft sent to the Reichstag, indicating that the new laws would apply to anyone with even one Jewish grandparent.

There is no question that in 1935 Hitler wanted to persecute everyone of Jewish descent. The Nazis called those with one or two Jewish grandparents Mischlinge, which translates to something like “mongrel.” Hitler despised the Mischlinge, calling them “monstrosities halfway between man and ape.” That the Mischlinge would eventually meet whatever fate awaited “full Jews” was a given. Hitler allowed the line stating that the legislation applied strictly to “full Jews” to remain in the public announcement of Nuremberg Laws only out of concern for Germany’s international reputation — the Berlin Olympic games were less than a year away.

The two different versions of the legislation led to considerable confusion. In November of 1935, a supplementary decree was added to the Nuremberg Laws in an effort to bring more clarity. Someone like Warburg, who had two Jewish grandparents, was defined as a “first-degree Mischling.” (Mischling is the singular of Mischlinge.) A person with only one Jewish grandparent was labeled a “second-degree Mischling.”

Though not subject to all the same decrees as “full Jews,” Mischlinge were still persecuted and treated as pariahs in German society. In the immediate aftermath of the passage of the Nuremberg Laws, they could be drafted into the army, but they would now be restricted to the lowest ranks; they could enroll in universities but were barred from the study of some subjects.

While working on Ravenous, I learned another surprising detail about Nazi racial classifications: it was possible to have one’s official status changed.

Considered neither “true” Jews nor “true” Germans, the Mischlinge were trapped in the middle of the Nazis’ twisted racial ideology. The Mischlinge, who often did not identify as Jewish, were shocked to be classified as second-class citizens. One official at the Reich Ministry of the Interior commented that the Mischlinge had it worse than the “full” Jews, who at least belong to a true community. The Mischlinge were stranded between two worlds: half-oppressed, half-oppressor.

While working on Ravenous, I learned another surprising detail about Nazi racial classifications: it was possible to have one’s official status changed. The process was informally known as Aryanization. The exact number of half- and quarter-Jews who applied to have their legal status changed in Nazi Germany remains unknown. Records of the Reich Ministry of the Interiorindicate thatby May 1941 nearly 10,000 Mischlinge had applied for an upgraded legal status of one type or another; 263 had been successful. Scholars now believe the true numbers of those who applied are considerably higher.

In 1941, after being evicted from his Kaiser Wilhelm institute, Otto Warburg submitted his own application for Aryanization. The application required photos (front and profile), military records, a written family history, and a statement of the applicant’s political views. Hitler was known to personally review such applications. Growing frustrated with the number of special cases he was asked to consider, Hitler once complained that Nazi Party members “seem to know more respectable Jews than the total number of Jews in Germany.”

Given that Warburg was a Nobel Prize winner, Hitler was likely involved in reviewing his application for Ayranization. But Warburg’s case lingered for months without an official decision. In the meantime, the question of what to do about the Mischlinge remained a source of frustration for the Nazis. On January 20, 1942, Nazi leaders gathered at the infamous Wannsee Conference to plan the “Final Solution of the Jewish question.” It was decided that half-Jews (first-degree Mischlinge) were to be treated as full Jews. Quarter-Jews (second-degree Mischlinge) would be assimilated into Aryan society.

The decisions made that January afternoon might have doomed Warburg and other first-degree Mischlinge, but some German officials continued to make the case that the Mischlinge should be sterilized rather than deported. Six weeks after the Wannsee Conference, senior Nazi officials gathered again, this time to arrive at a “Final Solution” to the Mischling question. At this second conference, overseen by Adolf Eichmann, the senior Nazis discussed the logistical problem of sterilizing tens of thousands of Mischlinge, even wondering about whether there was enough hospital space to do all the procedures. By the end of this second “Final Solution” conference, the Mischling question still had no definitive answer.

Though Warburg was never officially Aryanized, the Nazi leadership chose to protect him, seemingly in the hope that he would arrive at a cure for cancer, a disease Hitler and other high-ranking Nazis dreaded. Though the records are inconclusive, Hermann Göring, whose power and influence was then second only to Hitler’s, may have intervened on Warburg’s behalf. Göring once claimed that it was up to him to decide “who is a Jew and who is Aryan” — a statement that speaks to the underlying fiction of the Nazi racial classifications. In the end, whether someone counted as a Jew had less to do with one’s grandparents than with one’s perceived usefulness to the Nazis.

Sam Apple has written for The New York Times Magazine, Wired, The Atlantic, and NewYorker.com. He is on the faculty of the MA in Science Writing and MA in Writing programs at Johns Hopkins.