Image via Flickr/Paul Keller

Jeremy Dauber is the author of Jewish Comedy: A Serious History, out this week from W.W. Norton & Company. Earlier this week, he wrote about Jewish comedy as a means of survival, and as a “parable for questions of Jewish modernity.” He has been blogging here all week as part of Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

Once, the story goes, there was a man who made his way to the United States. Starting from nothing, he worked his way up the food chain to become a titan of industry. He brought all his relatives, including his aged mother, over from the old country and set them up in style, in magnificent apartments. He joined the finest of all country clubs, even those that had, heretofore, been restricted; and he purchased himself a two hundred-foot yacht. He dressed only in white, and insisted that everyone refer to him as the Captain. One morning, he was about to take the boat out, and asked his mother if she would like to join him out on the water, reminding her that, if she came along, she would have to refer to him by his preferred sobriquet.

She looked at him. “Benny,” she said. “By you, you’re a captain. By me, you’re a captain. But let me tell you something. By a captain you’re no captain.”

There are a surprising number of things going on in this brief joke. There’s the incorporation of a kind of Yiddish syntax into American Jewish English, and, simultaneously, the reinforcement of the identification of Yiddish, or Yinglish, with funny. (As a professor of Yiddish and Jewish literature, I have a lot to say about this identification and its problems; as a chronicler of the history of Jewish comedy, I’m just reporting a cultural phenomenon.) And there’s the vexed, difficult image of the Jewish mother, present here as killjoy, that draws on a vexed, problematic comic Jewish archetype in American Jewish comedy. But right now I want to focus on just one aspect of the joke: American Jewish success, and its discontent.

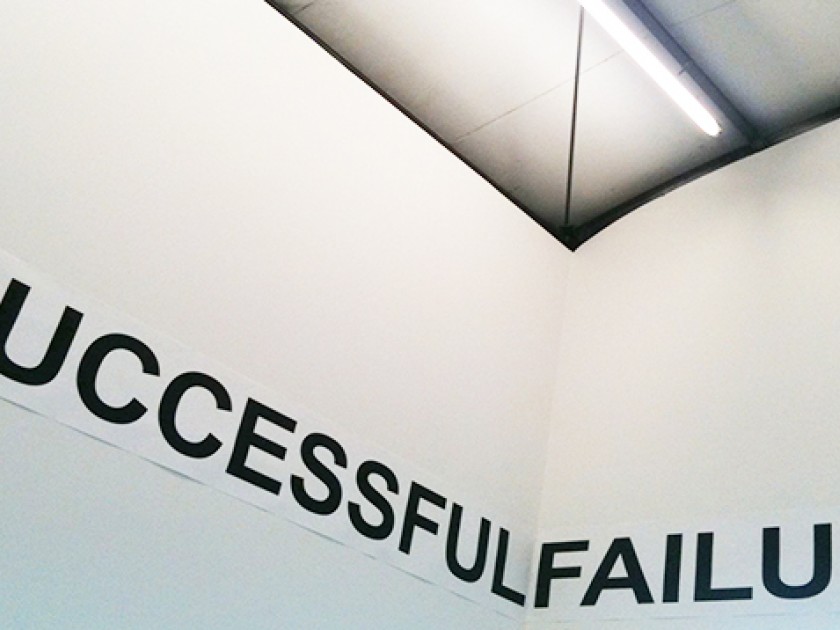

In my last post, I wrote about how Sholem Aleichem prodded at the anxieties that lay under the promise of Jewish emancipation: how there might be something in the Jewish ethos, or character, that might threaten, or even self-sabotage, the possibilities of Jewish success in the modern world. It may be fair to say that there is nowhere in the diaspora that Jews have achieved success the way that they have in the United States. And yet this joke asks — “by a captain you’re no captain” — what exactly that success might mean.

If we nod at the joke, if we find it meaningful, we do so precisely because we recognize some truth, present or past: that others, looking at the image of a Jewish yachtsman, find it incongruous, or oxymoronic. Is that still the case? If it isn’t, why does the joke resonate (if it does)? And if it doesn’t — if American Jewish acculturation has achieved such ground that we are willing to use the phrase “American Jewish sports hero” without pause — then have we entered a new phase of American Jewish comedy, one which is predicated not on difference, or alienation, but something else? And if contemporary Jewish comedy is based on difference and alienation, then what precisely does that difference consist of?

A lot of contemporary comedians — in a road that runs through, among many other sources, Seinfeld, Adam Sandler, the movies of Judd Apatow, and Difficult People—are explicitly or implicitly thinking about this question. Too long to discuss how they do so here (if only there were a book, a recently published one, say, that might treat this at fuller length…hm…), but suffice it to say, for now, that the question is not a new one.

One can even consider one of the first great works of Jewish diaspora living, the Book of Esther, as contemplating the same questions: what does Jewish identity mean, when it can be hidden and revealed, as Esther so famously does? The Book of Esther — which is, among many other things, a great comedy — ends with a triumphant revelation of Jewish identity on Esther’s part. (Well, actually it ends with a new tax, but that’s another story.) But how Esther lives, a queen of a wide-ranging empire and a Jew, that the narrative doesn’t tell us. Whither specific identity, in a world of success?

But this is getting a little too serious for a blog post about Jewish comedy. Let me just end, then, with one last joke, one Milton Berle used to tell, about the Tomb of the Jewish Unknown Soldier. On it is written, HYMAN GOLDFARB, FURRIER. Because as a soldier he was unknown, but as a furrier, he was fantastic.

Thank you all. I’ve been here all week.

Jeremy Dauber is a professor of Jewish literature and American studies at Columbia University. His books include Jewish Comedy and The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem, both finalists for the National Jewish Book Award, and, most recently, American Comics: A History. He lives in New York City.