Image via Wikimedia Commons

Anne Raeff is the author of the novel Winter Kept Us Warm (Counterpoint Press). She is blogging here as part of the Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

In the summer of 2008, my wife, Lori and I went to New Jersey to spend time with my father, who had recently been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (A.L.S.), more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. My father’s condition was deteriorating rapidly. He kept falling. Though for most of his adult life he had started his day with writing letters, his fingers were no longer strong enough to type, so I became his secretary, typing as he dictated. The letters usually went something like this: I am sorry that it has taken me longer than usual to respond to your letter, but I find that with each day I have less and less strength … My daughter, Anne, has been so kind as to offer her secretarial services, so I am taking this opportunity to write now, though, alas, I cannot take pen in hand to do so. My parents had recently moved to an apartment in a retirement residence, and my wife, my sister, and I stayed in their almost empty house, my childhood home. In addition to helping my father and spending as much time as possible with him, we took care of the final tasks of preparing the house to go on the market.

At the end of the summer the house was ready, my father had given up trying to walk and was permanently in a wheelchair, and we had to say goodbye. I am a high school teacher and the school year was starting, so I reluctantly went home to San Francisco. A week after my return, a package from my father arrived in the mail. It is time for you to be the keeper of these documents now, the note said. In the box were three sets of documents. They are what I like to consider my most precious inheritance. The first set contained my maternal grandparents’ passports issued in 1938 by the German Reich. They were stark documents. On each of their covers was an eagle with its wings spread, sitting atop a swastika. The passports contained the visas and seals tracking my mother’s family’s escape from Vienna to safety: Amsterdam, Panama, Chile, and finally Bolivia. The second group of papers consisted of my father’s exit and transit visas from France through Spain to Portugal, and then to the United States. He did not have a passport. Up until my father left Europe in 1941 at the age of eighteen, he had lived almost all of his life as a stateless refugee. My grandparents were Russian Mensheviks, Socialists who, in contrast to the Bolsheviks, did not believe in violent revolution. Still, in the early days, they supported the U.S.S.R, and my grandfather, an engineer, was sent by the Soviet government to Berlin to oversee the purchase of industrial equipment. In 1926, when my father was three, my grandfather was called back to the Soviet Union, but my grandparents decided, due to the increasingly totalitarian direction of Stalin’s rule, not to go home, becoming by that simple act of self-protection, stateless — citizens of nowhere.

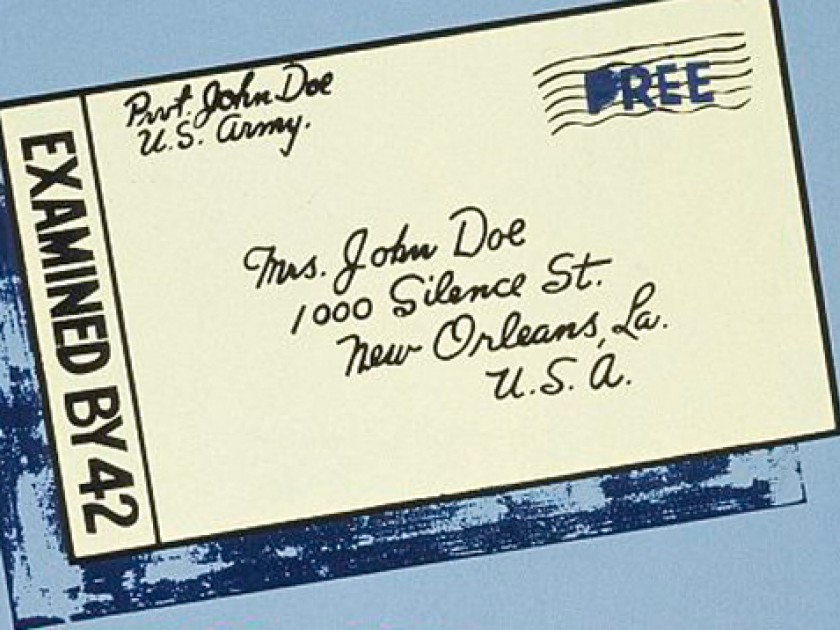

The final group of documents was a separate, familiar folder that contained twenty-five sheets of onionskin paper. Upon each sheet was a letter typed in German accompanied by my father’s awkward English translation. The letters were all dated June, July, or August of 1944 and were written by German prisoners of war at the P.O.W. camp in Arizona where my father was stationed. Not even a year after arriving in the U.S., my father had been drafted, and since he suffered from asthma and was not fit for combat, he served the war effort as an interpreter and a censor. After the war, my father went on to become a professor of Russian history. Recording these letters was, perhaps, my father’s first act as an historian.

When he first showed me these letters, he made no comment except to laugh and say that copying them was the most dangerous thing he had done as a soldier. When I finished reading them, he put them away without asking for my comments, so I never told him that I found them disappointing, banal even. They were mostly about being homesick and how at the camp they were given cigarettes and chocolates and ice cream. Some of them praised the Führer or worried about the outcome of the war, but I wanted more. I suppose I wanted to hate these soldiers, but there wasn’t enough cruelty and hatred in their words to stir up such an extreme emotion.

Despite my disappointment, I was drawn to the letters and, often, when my parents were out, I took them out of the file behind my father’s desk and reread them. I did not read them to imagine the atrocities that they had committed or witnessed. I read them imagining what it was like for my father to read them, to be confronted with the yearnings and fears, the sorrows and small pleasures of these soldiers, who, before they were captured, had been fighting for a regime whose principal goal was to rid the world of people like my father and his family. I imagined him trembling with anger. I imagined how difficult it must have been for him not to destroy the letters and, on top of that, to record them, knowing that so many people in Europe would never get the chance to write to their loved ones, let alone have their thoughts preserved for posterity. It was this act of imagination that led me, so many years later, to write my novel Winter Kept Us Warm. Indeed, every time I sat down at my desk to work on the book, I thought of my father, the young asthmatic refugee, the soldier, the Jew, recording for posterity the letters of the enemy.

As the novel began to take shape, the P.O.W. camp in Arizona became essential to the story. Yet, just as my father never wrote a book or article about the German prisoners, I too did not write about them. In Winter Kept Us Warm, the chapters that take place at the camp focus instead on what for me was the most compelling of my father’s P.O.W. stories. It is the tale of two Uzbeks, a father and son, who had not even known there was a war going on, but had been swept up by what my father called “the claws of history” and landed in the camp in Arizona. It was a story that I asked my father to tell me over and over again; he always agreed, even though it made me cry.

Still, though the letters are not part of my book, they are always nearby when I write. I keep them in a drawer in my desk, my father’s desk that I have also inherited. It is the desk he sat at to write about history and the one I sit at now to write fiction. So, I suppose the letters are part of the story after all. They are part of my father’s story, which is part of my story. They remind me that history is always part of the story.

Anne Raeff is the author of Winter Kept Us Warm (Counterpoint Press). Her short story collection,The Jungle Around Uswon the 2015 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. The collection is also a finalist for the California Book Award and was onThe San Francisco Chronicle’s100 Best Books of 2017 list. Her stories and essays have appeared inNew England Review,ZYZZYVA, andGuernicaamong other places. Her first novelClara Mondschein’s Melancholiawas published in 2002. She is proud to be a high school teacher and works primarily with recent immigrants. She too is a child of immigrants and much of her writing draws on her family’s history as refugees from war and the Holocaust. She lives in San Francisco with her wife and two cats.