This morning, as I walked 144 feet from my office to my favorite lunch spot, I passed five people asking for money. One has been standing outside my gallery three days a week for the past two years with a cardboard sign reading “Pregnant and Homeless” — the longest gestation in human history. Downtown Dan, who lives entirely on the spare change people drop into his guitar case, nodded hello as he sang and played. On days off and during bathroom breaks, he stores his guitar in a stairwell off our entryway. I got a friendly shoutout, too, from the tall guy who has been raising donations for “Black Boys At Risk” on and off for a half dozen years. He has newspaper clippings and official-looking government forms that he flashes at passersby, as he asks them if they care about kids. I have never checked the paperwork and vacillate between skepticism and belief. Next is someone I’ve never seen before, a white dude begging a bit more aggressively than the regulars. I look him in the eye, acknowledging his humanity, as I have been taught, and hope the old-timers will come to my aid if need be. Then, because it is the season of giving, I see a red-suited Santa shivering while ringing his Salvation Army bell.

One friend drops a dollar into every pan he passes. Another chooses one lucky recipient daily for a ten-dollar bill. A third only gives food so that his money is not spent on drugs or liquor (though he often spends his money on those exact things for himself). But is that our business?

In 1791, the writer Samuel Johnson, in answer to the same questions, asked, “Why should the poor be denied such sweeteners of their existence?”

In 2017, Pope Francis said, “Give them the money, and don’t worry about it.”

Saint Francis of Assisi would probably avoid the question entirely and prefer to do the begging himself: “Grant me the treasure of sublime poverty.”

Had I continued up the street to the library in my small, mostly liberal, good-hearted, upper-middle class, college-educated, American town, I could have seen, in the same room where I have read my poetry, the unhinged door to the law office of Silent Cal Coolidge, our former mayor and US president, whose six memorable words, “the business of America is business,” has one hundred million more Google hits than the words of our sister town’s residents, Robert Frost — “Good fences make good neighbors” — and Emily Dickinson — “Hope is the thing with feathers.” Our current mayor encourages us not to give to individuals, but to drop our change “into the mouth of the Happy Frog donation station,” where money is collected to help fund soup kitchens and shelters.

After lunch, I sit at my desk and open appeals from local arts organizations. It is that time of the year: the giving season. Two philanthropies have added a note penned to me personally. Next, I open my synagogue’s annual appeal. Shall I check “anonymous,” or add my name to help encourage others to give?

It is that time of the year: the giving season. Two philanthropies have added a note penned to me personally. Next, I open my synagogue’s annual appeal. Shall I check “anonymous,” or add my name to help encourage others to give?

Philosopher Peter Singer tells us, “We need to get over our reluctance to speak openly about the good we do. Silent giving will not change a culture that deems it sensible to spend all your money on yourself.” This has become the mantra of what is now known as “effective altruism.”

Jesus Christ disagrees. “When you give to the needy, do not announce it with trumpets, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and on the streets, to be honored by others.”

I think about the hypocrites who both trumpet and give less than promised. This week’s newspaper headlines exposed two billionaires whose charitable foundations gave less than the law requires.

How much shall I give? To how many? How often? Am I doing enough? What are we teaching our children as we walk past the panhandlers?

My wife urges me to give joyously! “The more we give, the happier we become,” she says, quoting Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh.

But I admit, I mostly give as an obligation, and not cheerfully. I wish I were a better person.

“Relax,” says Moses ben Maimon, better known as Maimonides (or the Rambam in Hebrew), a rabbi, doctor, astronomer, lawyer, and scholar, who is considered the greatest Jewish philosopher of the Middle Ages and, for many, of all time. “You are already on the first rung of the Golden Ladder.” There is no place to go but up.

Maimonides lived from 1138 to 1204 and was born under Muslim rule in what we now call Spain. He is also well regarded in Islamic countries for his scientific and medical writings. In his first major book, the Mishneh Torah, he explains the reasons behind Jewish laws and practices and invents an eight-step ladder that leads to a fair society.

- The first rung of the ladder is when a donation is given, but given reluctantly.

- The second rung is when you give cheerfully, but less than you should.

- The third rung is when you give to the poor after being asked.

- The fourth rung is when you give to the poor before you are asked.

- The fifth rung is when the donor does not know the name of the recipient, so the donor can’t give in to pride if the two pass each other on the street.

- The sixth rung is when the donor gives anonymously, so the recipient does not feel shame or indebtedness if they pass each other on the street.

- The seventh rung is when neither the receiver nor the giver knows each other — so neither pride nor shame are possible.

- The eighth and highest rung on the ladder is when you create a job for someone, or loan them enough to start their own business, so they can care for themselves and give charity to others.

Maimonides’s father taught him that the word of God obligated all Jews to give 10 percent of their earnings to people in need. You were allowed to give up to 20 percent but not more — so you didn’t end up having to rely on charity yourself. (Dear top one-percenters: Maimonides made an exception for the very wealthy.)

Most of us travel up and down that ladder, depending on the day, yet we still tend to think of charity as an act of helping those less fortunate. I praise myself when I put some coins in a beggar’s cup or write a check to a charitable organization.

But tzedakah, the Hebrew word for charity, has a different meaning. In Judaism, giving to the poor is not viewed as generosity, but rather as an act of justice, fairness, and righteousness all rolled into one; it is a sacred and ethical obligation.

Maimonides says that it is humbling to help another human with less than ourselves, because we know that we could just as easily be in their position. And the poor should not feel ashamed, for God could have just as easily given them all they need. Maimonides thought of tzedakah as a partnership between the rich and the poor. If anything, it is the giver who should thank the receiver, for allowing them the opportunity to do a good deed.

Even Calvin Coolidge understood that “no person was ever honored for what they received. Honor has been the reward for what they gave.”

Tonight, on my walk home, I saw Downtown Dan a few feet in front of me. I watched as he emptied the coins from his guitar case. He counted out one third to put in his pocket, dropped a third into the mouth of the Friendly Frog, and the final third he distributed to those even more in need and, humming to himself, he continued on his way.

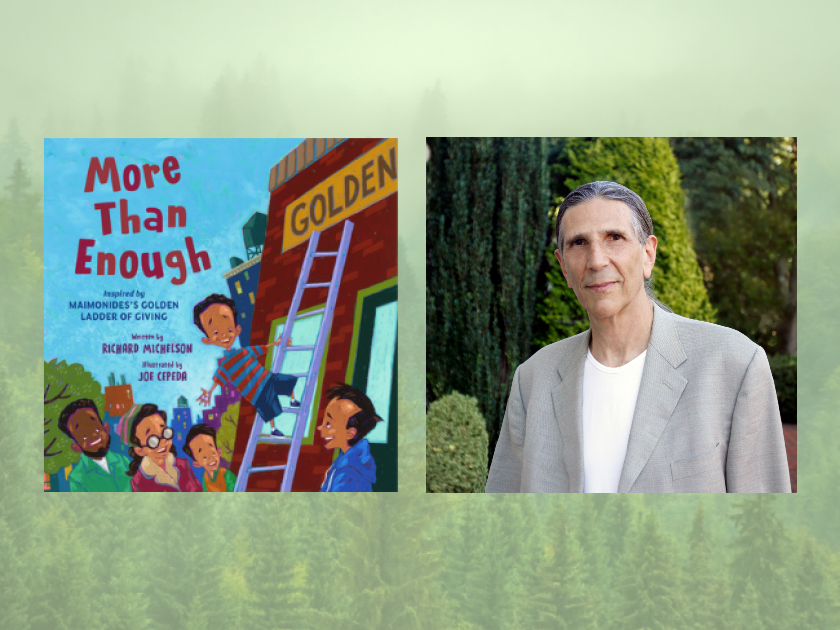

Happy publication day to More than Enough: A Story Inspired by Maimonides’s Golden Ladder of Giving, written by Richard Michelson and illustrated by Joe Cepeda!

Richard Michelson’s books have been named among the Ten Best of the Year by The New York Times, Publishers Weekly, and The New Yorker; He’s received a National Jewish Book Award (and twice finalist) and two Sydney Taylor Gold Medals (and two silver) from the AJL. Born in Brooklyn, Michelson lives in MA and owns R. Michelson Galleries.