Upon hearing the words “rabbinical dress,” many think of the vestments worn by rabbis in synagogue during the High Holy Days: tall, ceremonial cantoral hats, tallitot, perhaps a yarmulke as well. In Sydney, Australia, where I live, and other places with dominant Ashkenazi Orthodox communities, images of long-bearded men wearing black felt fedoras and suits certainly come to mind. Both archetypes of rabbinical dress are the result of the Haskalah and the subsequent emancipation of European Jewry over the course of the long nineteenth century.

My book, Jews in Suits: Men’s Dress in Vienna, 1890 – 1938 (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023), explores the meaning and function of clothing in the creation and performance of masculine identities among Vienna’s acculturated and assimilated Jews in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When I was conducting research for Jews in Suits, the clothing of rabbis — a profession that by its very nature speaks to Jewish “distinctiveness” — was not the first thing I considered. However, rabbis were central to the transformation and modernization of European Jews — not only in Vienna, but across the continent — and this is reflected in their clothing choices.

The stereotypical image of the rabbi as a (sometimes elderly) man with a long beard, curled payos (sidelocks), a dark kaftan, and a high fur cap — an image commonly associated with Hasidic Jews in New York, Jerusalem, Melbourne, and Antwerp today, and Central and Eastern Europe before the Holocaust — has its origins in the pre-Haskalah period. There are varying hypotheses about the origins of this particular style of dress, but what we know is that due to the transnational nature of world Jewry, rabbinical vestments originally associated with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth spread to other parts of Europe and further afield. Particularly in the context of pre-Haskalah Ashkenaz, many rabbis, whether Polish or not, appeared in this archetypal rabbinical guise.

However, the winds of change brought in by the Haskalah transformed both the role and appearance of European rabbis. Just as rabbis adapted to or were responsible for adapting Judaism in this period (by introducing reforms to synagogue services and daily Judaic practice), so too did they adapt their sartorial image. In Vienna, as in many other centers of German Jewry, rabbis encouraged their flock to regard themselves not as “Jews” but rather as “Germans of the Mosaic faith.” While it took time to learn the manners and mores of the Austro-German bourgeoisie, and to abandon dialects of Jüdischdeutsch and Yiddish for Hochdeutsch (or its Viennese variety), dressing in the latest styles was a quick and visually obvious way of self-fashioning as a modern European.

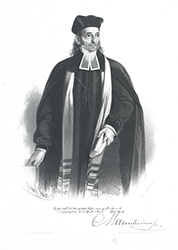

Rabbi Isak Noa Mannheimer, lithograph by Eduard Kaiser, 1858, via Wikimedia Commons.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, rabbinic attire evolved to resemble that worn by Christian faith leaders. Rabbis across Europe (and beyond) dressed in relatively uniform styles that consisted of long, black, cassock-like robes; white clerical bands similar to those worn by Christian preachers and members of the legal profession; thin, stole-like tallitot; and head coverings of various styles.

Chief Rabbi of France Zadoc Kahn, photographed by Nadar, c. 1875 – 1895, via Wikimedia Commons.

Unsurprisingly, in different parts of Europe, the variety of headwear worn as part of rabbinical vestments tended to reflect what was worn by the dominant denomination of Christian faith leaders. For example, in Paris, where Catholicism was the dominant religion, rabbinical hats were wide and galero-like in style, with a slightly curled brim, like those worn by Catholic priests and bishops.

Hermann Adler, Chief Rabbi of the British Empire, photographed by W. & D. Downey, 1892, via Wikimedia Commons.

In official portraits, chief rabbis of the United Hebrew Congregations of the British Commonwealth — such as the German-born Nathan Marcus Adler (1803 – 1890) and his son and successor, Hermann Adler (1839 – 1911) — wear tall, black, octagonal mitznefet (so named for the turban worn by the high priests in the Jerusalem temples), a departure from the Canterbury- and shovel hats sported by members of the contemporaneous Anglican clergy.

Viennese Rabbi Adolf Jellinek, by Hermann Schmid, 1850, via Wikimedia Commons.

This was similar in Vienna, where chief rabbis wore headgear in a variety of styles resembling those worn by the dominant Catholic clergy, but also those worn by Protestant ministers and Orthodox priests.

Despite the similarity of dress, we should avoid viewing sartorial adaptability as assimilation. Differences between the vestments of rabbis, priests, and ministers still remained, notably in the inclusion of the tallit (even if a narrower variety that resembled the stole was worn by Christian faith leaders). Even the cassock-like robe, referred to in German as a Talar, differed between the clergymen, as indicated by the cutting instructions provided in the 1911 textbook of the Viennese Tailoring Academy. Rather than assimilating, dressing in the rabbinical uniform allowed rabbis and cantors to make statements about their public personas both as members of the Jewish clergy and as Germans.

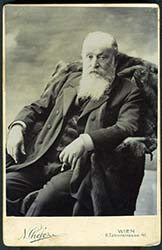

The private sartorial personas adopted by rabbis is another matter entirely. Examining photos of Viennese rabbis “off duty” at the turn of the twentieth century, one is struck by the mundanity of their attire. Like other urban, middle-class men of the period, they are dressed in the ubiquitous tailored three-piece suit, probably in the familiar blacks, grays, browns, and blues that were prevalent at the time. In many of these photographs, which depict rabbis at home or posing for the camera in photography ateliers, there is nothing perceivably Jewish about their attire; many even go bare-headed.

Studio portrait of Rabbi Moritz Güdemann, photographed by N. Chefez, via Leo Baeck Institute, F 001 AR 7067.

In a famous portrait of Viennese chief rabbi Moritz Güdemann, taken around the turn of the century, the sitter is relaxing in a winged armchair, wearing a dark, three-piece, double-breasted suit, with a fob chain stretched across his belly and the stub of a cigar dangling between his fingers. He looks more like an aging plutocrat than a rabbi leading his congregation.

Rabbi Güdemann’s attire is not unique; off-duty rabbis did not dress in their synagogal vestments but rather like other urban men, both Jewish and non-Jewish. But in a strange subversion of oft-quoted maxim by Russian-born maskil Judah Leyb Gordon, “Be a man in the street and a Jew in your tent” (1863), Güdemann, like many other European rabbis, dressed like Jews in the street and men at home. Clothing might seem trivial, but exploring the way Jewish people dressed in the past reveals a lot not only about the individuals in question, but also about Jews and their place in society during periods of social and cultural change.

Jonathan C. Kaplan-Wajselbaum is an honorary adjunct fellow at the University of Technology Sydney and education officer at the Sydney Jewish Museum. He holds a PhD in dress and design history from the Imagining Fashion Futures Research lab at the University of Technology Sydney, and has published on the intersections between dress, acculturation, and Jewish identity.