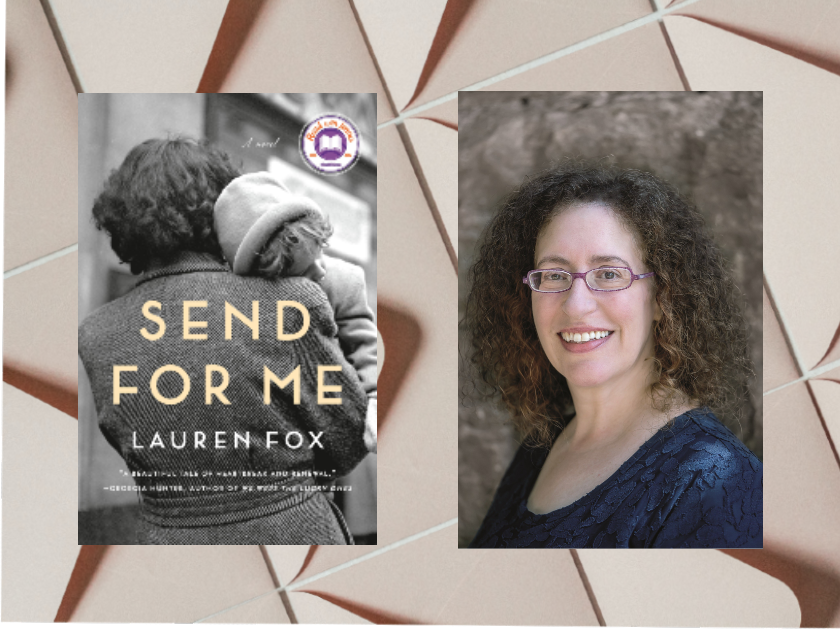

Photograph of Lauren Fox by Rachel Dickman

With The Diary of Anne Frank as a prime example, readers look to the written traces — journal entries, letters, stories — left behind by victims of the Holocaust in order to piece together who they were and what occurred. In Send For Me, Lauren Fox uses the letters of her grandmother, who perished in the camps, as a starting point in a fictionalized story of her own family history. JBC’s Editorial Fellow Ariella Carmell and Fox discuss the writing of this novel and what she learned in the process.

Ariella Carmell: This book draws from your own family history. Why did you decide to write it as a novel instead of a memoir?

Lauren Fox: I started working on this project many years ago, when I was in graduate school. Originally, it was a memoir, but something about it just didn’t work. Partly it was that I was too young at the time to have enough material for a memoir, but even more than that, I just got kind of paralyzed by the genre, because in memoir, everything has to be from the author’s perspective. When I finally realized that I could shape this material into a work of fiction, it blew everything wide open for me. I could imagine the points of view of so many other characters and I could invent dialogue and scenes — all based on the letters and on my family members, all remaining true to the actual story, but without the stifling obligation to keep it limited to my point of view.

AC: What inspired the idea for Send for Me, and how does the final product differ from your original conception?

LF: I think maybe I answered the second part of that question in my first answer; my original conception of this was that it would be non-fiction! The story is inspired by my family’s history. My grandparents and mother emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1938, when my mom was a toddler. My family was very close, but I grew up with only a vague understanding of where they came from and what had happened to them. As I got older, I became very interested in trying to understand the psychological underpinnings of my family, the closeness and the love mixed with so much worry and fear.

When I was in my twenties, not long after my grandparents had died, I stumbled upon a box of letters in my parents’ basement. They were dated from 1938 to 1941 and were written by my great-grandmother, in Germany, to my grandmother, who had just settled in Milwaukee. I had those letters translated, and they became the real, concrete basis for this novel. They are full of all of the love and longing and fear that suffused my upbringing.

AC: What was the research process for this novel like?

LF: The research process for the book was truly fascinating. I mean, besides getting the letters translated, which was pretty laborious, I read a ton about the time period. And although of course it was a difficult era to explore, I just loved doing the research — I felt like with each detail I uncovered, I was learning more and more about my own family’s story. It was also really fun to do a deep dive into the physical details of the time; for example, if I wondered what kind of shoes a character would be wearing in 1937, or what style of dress, I was able to find out the specifics of the fashion of the time. For the section of the book that takes place on the ship, I found brochures advertising trans-Atlantic crossings in 1938. I loved all of that.

When I was in my twenties, not long after my grandparents had died, I stumbled upon a box of letters in my parents’ basement.

AC: Did Klara’s letters resemble your own family letters, or were they completely fictionalized?

LF: The book is fiction, but, aside from the names, I didn’t change a word of my great-grandmother’s letters; they appear in the book exactly as she wrote them. That was really important to me. I felt like I had a responsibility to stay true to her words.

AC: In writing fictional versions of your grandmother and mother, did you find yourself gaining a new perspective on your relationship with them? If so, how did this process affect your relationships with them?

LF: You know, it didn’t change my relationship with them — I feel lucky that our relationships were and are very loving and uncomplicated. But it did kind of give me access to a piece of my grandma that I’ve missed for thirty years, and that was really lovely. It made me feel very connected with her again, almost like when you dream about somebody you loved who is gone.

AC: The character of Clare most closely resembles you in terms of autobiography, but is she the character you feel the closest to?

LF: Clare is the character I most desperately did not want to write! My first draft of the novel was only the historical part, only the sections that take place in Germany, on the ship, and then the early years in Milwaukee. But on reading that draft, my editor really felt like a piece of the story was missing, and she encouraged me to write a contemporary section. She understood before I did that this book was about what is handed down to us. I was reluctant — but when I sat down to do it, Clare’s section came pretty easily to me. I don’t think I feel the closest to her, but she was revelatory in some ways — writing about her relationship to the past definitely illuminated my own experience.

AC: How does being the descendant of Holocaust survivors affect your outlook on the world and how you approach your writing?

LF: That’s a big question! I think I share this guiding principle with many Jews and others whose families have faced persecution: that we don’t exist only for ourselves, that we owe something to the rest of the world, that it’s our obligation to speak and act against suffering and injustice. That sentiment reflects my sense of who I am, so naturally it makes its way into my writing, even when I’m not writing explicitly about the Holocaust.

AC: What is something you learned during this project that surprised you?

LF: I was quite surprised to learn how different the experience of German Jews was to the reality of Eastern European Jews and, to some extent, Jews in other Western European countries in the lead-up to World War II. In retrospect it seems obvious, but of course German Jews lived with increasing oppression throughout the 1930s, whereas for Eastern European Jews, things happened much faster. More German Jews than Jews from other countries were able to leave because they were confronted with these increasingly dehumanizing and humiliating restrictions on a daily basis. When I realized this, it felt simultaneously shocking and clarifying to me.

AC: Which novels or other works of art influenced the creative process of Send for Me?

LF: It’s not a novel, but I was most influenced by a book called Between Dignity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany, by Marion A. Kaplan. In it she focuses specifically on the experience of Jewish women during the run-up to the war. This book filled in so many historical details for me, and it gave me a really rich sense of the macro-level situation in Germany.

AC: What are you working on and reading now?

LF: I’m just at the very beginning stages of my next project — too soon to talk about, but I’m excited to start something new. I just started reading The Remains of the Day, which has been in my to-read pile for ages.

Ariella Carmell is a Brooklyn-based writer of plays and prose. She graduated from the University of Chicago, where she studied literature and philosophy. Her work has appeared in Alma, the Sierra Nevada Review, the Brooklyn review, and elsewhere.