On an unusually sunny February afternoon in 2009, the well-known Ladino folk singer Flory Jagoda drove me through the streets of Alexandria, Virginia. I remember little of the drive to the metro station, but I recall questioning my sanity as the car sped through the streets, heading toward the yellow line’s Braddock Station. Flory Jagoda careened through the streets as I continued to interview her. Her responses were quick, enthusiastic, and filled with advice and reflection.

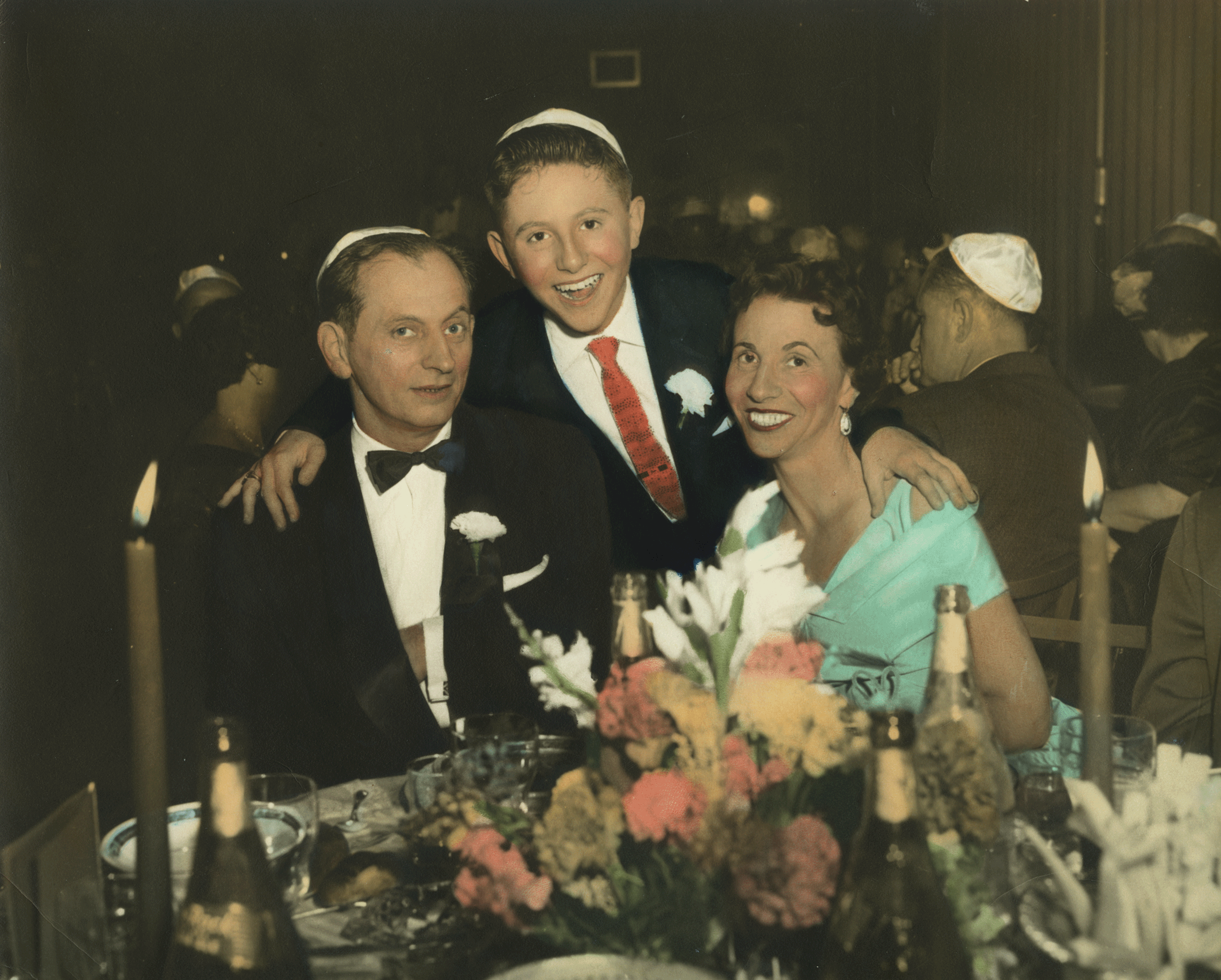

I had spent the day with her and her husband, Harry, in their comfortable Virginia apartment overlooking the water. We examined photographs, lovingly cradled her accordion, listened to musical selections, and reminisced about their family and friends. Flory was the fourth Jewish war bride I interviewed for my book Between Two Worlds, and the only one whose husband was still alive. When we spoke, it took time for her and Harry to talk about their courtship and wedding. Both felt most comfortable with the narratives they had repeated over the last few decades. By the time I met her in 2009, Flory had been interviewed several times and had been the subject of the first documentary film concerning her life. She and Harry were not accustomed to disclosing details of their courtship and marriage. Those had not been the foci of their previous interviews. I noticed this pattern in many of the interviews I conducted for Between Two Worlds.

During my research, I was fascinated by the paradox of Jewish war brides whose Holocaust survival narratives had become well known by the early twenty-first century but whose stories about meeting and marrying military personnel remained — at most — a footnote in their life stories. As a young professor of history, several of the memoirs I assigned were written by female survivors who concluded their books with a brief description of their life-altering encounters with the American, British, or Canadian military personnel they later married. My students and I began with Gerda Weissman Klein’s 1957 All But My Life. Later, I assigned the memoirs of Leesha Rose, Gena Turgel, Clara Isaacman, Anne Fox, Judith Isaacson, and Lala Fishman, all Jewish war brides. Like Flory, these women also participated in interview projects, often consenting to being interviewed multiple times. Likewise, several of these women participated in projects that lay outside of the traditional realm of memorialization; Flory preserved songs of her prewar life in Yugoslavia, Gerda authored two children’s books, Leesha produced plays concerning the resistance, and Clara developed a Holocaust education program for high school and college aged students.

While these women developed strong self-reflections as survivors later in their lives, most spent the first few decades after the war revealing little about what had happened to them during the Holocaust. Even those who shared their experiences in the immediate postwar period tended to be silent once they settled into their new homes. Leesha, for example, was celebrated as a war hero when she first arrived in Canada and spoke with newspaper reporters when she immigrated to Toronto. By the early 1950s, however, she had ceased speaking about her experiences in the resistance or her personal losses during the war. That mirrored Gena’s experiences. Gena had also been interviewed immediately after she left Germany and arrived in London, but she stopped sharing her story once she moved into her in-laws’ home. Even when she felt an urge to record her experiences, the Bergen Belsen survivor remained quiet, secretly writing her memoirs in a mixture of Polish and English before hiding them away.

Many Jewish war brides began to discuss their war time experiences when their children reached adolescence and adulthood. After maintaining decades of silence, Leesha shared her past with her son when he inquired about her Holocaust experiences. According to her recollections, this questioning made everything “tumble out,” and within a decade, she transitioned from quietly divulging her painful past to her children to becoming heavily involved in Holocaust education efforts, publishing her memoir in 1978.

While many European and North African Jewish World War II war brides consented to interviews in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s, there were several who never publicly shared their experiences. Some of these Jewish war brides could be located only in the archival record; others emerged because they had been remembered as survivors by their children and grandchildren. My grandmother exemplified this latter category. In many ways, it was my grandmother’s experience, alongside the memoirs and interviews by women such as Flory and Gerda, that drove me to write Between Two Worlds: Jewish War Brides After the Holocaust, a history of the Jewish survivors who married American, British, and Canadian military personnel.

Between Two Worlds offers a different way of thinking about the Holocaust and its aftermath. I wanted to know more about survivors like my grandmother, Gena, and Flory: women and men who immigrated under a special category with separate visas and traveled on ships, trains, and planes paid for by the Allies. These Jewish war brides and their spouses floated between war bride, survivor, and military communities, never fully belonging to one or the other. They created families grounded in the traumas of both the Holocaust and World War II, having unique opportunities to create Jewish lives and Jewish communities after unspeakable trauma. My interview with Flory and her husband was one piece of a larger narrative on this overlooked story and provided me with the opportunity to introduce her and other lesser known heroes into histories of the Holocaust and World War II.

Robin Judd is an associate professor of history at The Ohio State University, where she directs the Hoffman Leaders and Leadership in History Fellowship program. Robin serves on the State of Ohio’s Commission for Holocaust and Genocide Education and Memorialization and is the immediate past president of the Association for Jewish Studies, the largest international society for scholars interested in Jewish Studies.