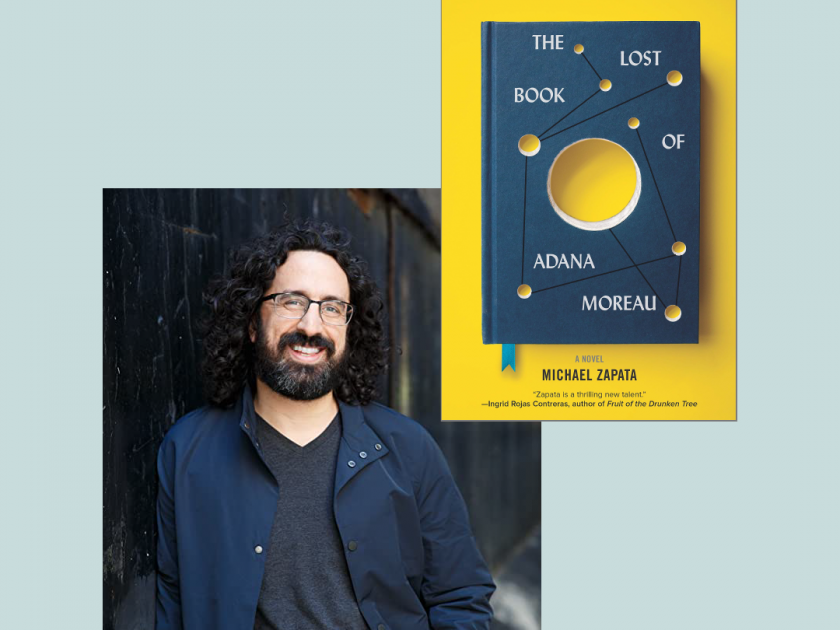

We spoke to Michael Zapata, author of The Lost Book of Adana Moreau, on May 6th as part of our JBC Authors at the Table series—you can watch the thirty minute chat here. Check out below some questions we didn’t have time for and keep the conversation going. See the whole lineup for JBC Authors at the Table.

Just as you show America to be a hybrid of different cultures, so too you show literature to be a hybrid of different genres. This book covers everything from science fiction, to journalism, to history, to works on physics… What do you see as the relationship between different genres? How can each one enhance the other?

My father is an immigrant from Ecuador and my mother’s family descended from early twentieth century Lithuanian Jewish refugees. I grew up between continents, languages, and histories, which is to say in liminal spaces. Those indistinct spaces feel very comfortable and apt to me when it comes to genre too, as if each genre itself were a world with its own evolutionary lineages and generally functioning rules, which, of course, can be embraced, bifurcated, defied, erased, upended, or merged with others. With climate change, late-capitalist horrors, and this terrible virus, the twenty-first century already feels increasingly uncanny, so maybe even the concept of genre has to be reinvented. I adore writers like Yuri Herrera, Idra Novey, Katy Simpson Smith, and Samantha Schweblin who are doing that work. Maybe we even need a new type of literature in which different genres, like particles at the quantum level, blink in and out of existence — a literature, in any case, that reckons with our era of unstable reality.

In the book, Javier tells Saul that his grandfather’s history books “present portraits of people rather than accounts of events” — do you feel as though your book does the same?

In the preface to his Memory of Fire Trilogy, which excavates and eviscerates some five hundred years of Latin American history, Eduardo Galeano writes, “I was a terrible history student. They taught me history as if it were a visit to a wax museum or to the land of the dead. I was over twenty before I discovered that the past was neither quiet nor mute.” That discovery is absolute fire. It’s the human voice, the vox humana, as the great oral historian Studs Terkel called it. In fact, in my novel, Saul’s grandfather and his work are unabashedly based on Studs Terkel, who did as much for the field of history as he did for fiction. The novel as a form with all its chaos, fear, desire, and even love allows for a direct confrontation with history as recorded (or largely invented) by elites. What emerges from our historical daze when we allow people to tell their own stories is meaning, remembrance, and, occasionally, rebellion.

It was interesting to bring in the comparison with Terezín. Have you been there?

Nazi leaders referred to Terezín as a “model ghetto,” but like everything with fascism that was a terrible illusion. Some prisoners worked and were even entertained when foreign journalists visited, but most were tortured and left to appalling conditions which resulted in mass death. Prisoners were even forced to contact family members to tell them they were being treated well. Fascism is inherently a fiction of madness — a nationalism that manufactures its own reality and sets out to erase all other realities. It’s the anti-multiverse. I’ve never been to Terezín, but I did speak to survivors of the Dirty War in Buenos Aires and they occasionally made comparisons to horrific Nazi practices, especially in places like the Navy Mechanics School, which was used as a secret detention center during the Dirty War and which is where that comparison in my novel originates from. Tens of thousands were disappeared into the abyss.

The opening quote: “Truly do we live on Earth?” — Nezahualcoyotl. What is the significance of this in the novel?

Although Nezahualcoyotl was a fifteenth century ruler of the city-state of Texcoco, he is often best remembered as a poet, one who interrogated reality and what the Nahuas then referred to as our “slippery Earth.” I love that phrase “slippery Earth,” even if I’ll never understand it. But I think it does feel like a certain state of living. Literature has always had notions of this sort of unreality or otherworldliness, and I’m fascinated with how both literature and theoretical physics try to describe the unseen and ask the essential question: what if? In their own ways, each character in my novel and I hope the novel itself contends with this concept of “what if” and the multiverse. Nezahualcoyotl died in 1472, just twenty years before the Columbian exchange and the collision of two Earths. He was right to ask that question.

What is your writing practice like in quarantine versus in regular times?

On walks around my neighborhood in Chicago, when others pass by in masks, my three year old son now says, “Daddy, move, there’s people,” and so we move to the grass and he watches them walk by, very still, even calm, like he’s watching something immovable, which is to say normal, and my heart breaks for him. I’m not writing, not really. My wife, a fifth through eighth grade art teacher at an International Baccalaureate public school, and I are working from home with our two sons so there is less and less time for reading and writing, but between slices of quarantine life — between the ceaseless lunches, the diapers, the half-blurry work Zoom meetings, the reality flattening Zoom burial of my dear uncle in Ecuador, the fiery tantrums and hugs, the sleepless nights, the stacks of email and unanswerable concerns, the grocery orders which take half a day, the mesmerizing LEGO cities — I’m somehow, if fleetingly, thinking more about fatherhood, the trepidation of loss, the fall of empire, America’s mass amnesia happening in real time etc. Of course, I don’t have any conclusions. I’m suspicious of anyone with a conclusion right now, but I do take solace in Roberto Bolaño’s words about writing in his masterpiece 2666: “In a word: experience is best. I won’t say you can’t get experience by hanging around libraries, but libraries are second to experience.”

Michael Zapata is a founding editor of MAKE Literary Magazine. He is the recipient of an Illinois Arts Council Award for Fiction, the City of Chicago DCASE Individual Artist Program award and a Pushcart nomination. As an educator, he taught literature and writing in high schools servicing dropout students. He is a graduate of the University of Iowa and has lived in New Orleans, Italy and Ecuador. He currently lives in Chicago with his family.