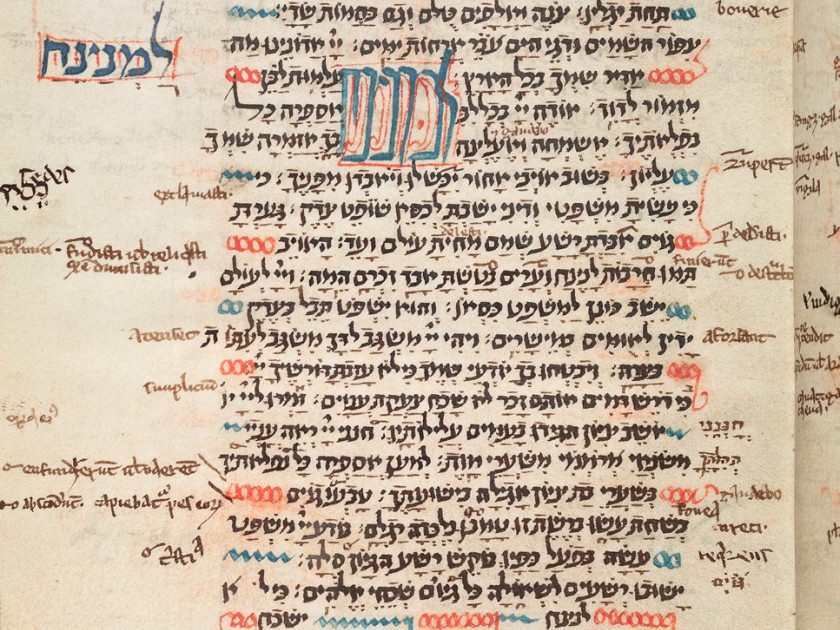

Thirteenth century Hebrew Psalter

For me, one of the most interesting, and pervasive, challenges in translating the Hebrew Bible with an eye to its literary power, was trying to find ways to bridge the substantial gap between ancient Hebrew and modern English. Some of the features of this gap proved to be insuperable, such as key terms in biblical Hebrew that had no real equivalent, or dangerously too many equivalents, in modern English. But the essential difference between the two languages is chiefly manifested in the terrific compactness of biblical Hebrew in comparison to modern English. Biblical Hebrew has a relatively small number of polysyllabic words, and because it is a language in which the syntactic and semantic function of words is typically indicated merely by the way verbs are conjugated, or by suffixes added to nouns, it has little need to use personal pronouns — to cite a central instance — although the language certainly has them and can introduce them at points for emphasis.

Here is a modest but characteristic instance: The only way to render the beginning of Psalm 23 in English is, as all translations do, “The Lord is my shepherd,” five words, six syllables. But the Hebrew is two concise words, four syllables, YHWH ro’i. No “my” is required because a first-person possessive suffix, a single syllable, is tacked onto the word for shepherd. The Hebrew does not even show “is” because the verb “to be” has no present tense, being merely implied by putting together a subject-noun and a predicate-noun. In this particular case, not much is lost by the added words and the additional two syllables in the English, but this very brief sentence and its English equivalent do illustrate the general problem, for very often the compactness of the original is crucial for its expressive force both in poetry and in narrative prose.

Some of the features of this gap proved to be insuperable, such as key terms in biblical Hebrew that had no real equivalent, or dangerously too many equivalents, in modern English.

My general strategy has been to eliminate all unnecessary words — in Psalms, not “happy is the man” but “happy the man” — and as much as feasible to avoid polysyllabic words, which in practice means favoring the Anglo-Saxon component of English over terms derived from Latin and Greek. I eliminated, for example, “iniquity” everywhere in my translation and for the Hebrew ‘avon used “crime,” a word that happens to derive from Latin but is a blessed single syllable.

Let me offer an example from Psalms where I think a small maneuver to tamp down English contributes to conveying the poetic force of the Hebrew. In Psalm 30:10, the beginning of the verse in the King James Version reads, “What profit is there in my blood.” The 1611 translation set the words “is there” in a different font because they are merely implied and don’t actually appear in the Hebrew. The decision to add those two words is unfortunate because anyone with an ear for poetry will recognize that this line has no perceptible rhythm. Modern translations produced by committees often seem to be guided by the assumption that everything must be made crystal clear; “blood,” for example, is changed to “death.” My rendering is, “What profit in my blood.” The “is there” struck me as altogether unnecessary, and what results is a replication of the Hebrew rhythm: MAH BEts’a bedaMI (uppercase marks the accented syllables). The pounding rhythm is important for the expressive effect of the line: it registers the desperation of the speaker urgently imploring God not to let him die. As elsewhere, rhythm is inseparable from meaning.

This microscopic example is a small illustration of what I have tried to do throughout my translation of the Bible and especially of the poetry. By tamping down English, as I have said, I have aimed, and perhaps even often succeeded, to convey in translation the rhythmic force and integrity of the strongest Psalms, the Book of Job, the poetry of the prophecies of Isaiah, the Song of Songs, and the other great poems of the Bible, many of them unique achievements in the ancient world. No translation, of course, can be more than an approximation of any magisterial work of literature, but I have worked in the conviction that a reasonable approximation is far better than the English versions that obscure the brilliance of the literary vehicle through which the biblical writers conveyed their vision.

Robert Alter is a professor of the Graduate School and emeritus professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley. His many books include The Pleasures of Reading in an Ideological Age, Imagined Cities: Urban Experience and the Language of the Novel, and Pen of Iron: American Prose and the King James Bible (Princeton). He lives in Berkeley, California.