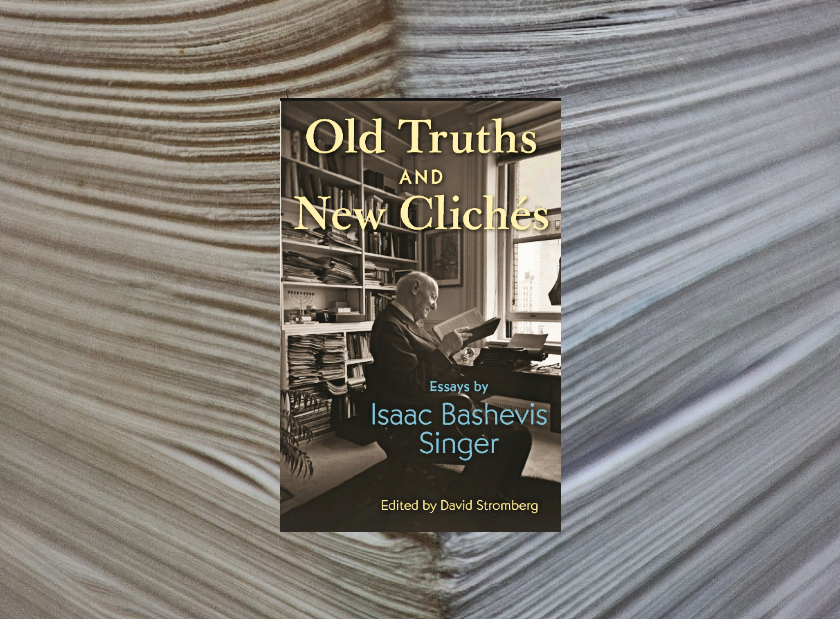

The question of which pieces would make it into the collection that became Old Truths and New Clichés: Essays by Isaac Bashevis Singer remained open until the very last moment. In normal circumstances, such decisions would have been made before the manuscript was delivered for typesetting, but in this case, the dynamic way in which Isaac Bashevis Singer wrote, rewrote, and rethought his ideas created dilemmas that carried themselves into the production process. For this book to be the best that it could, editorial changes were made in the proofing stage – essays were removed and paratexts were revised – because the process of working with Singer’s material for so many years created a kind of fog that only lifted at the last minute when all the pieces were falling in place.

There are at least three different versions of this collection in draft form. The first version put all of Singer’s essayistic nonfiction from the archives into the volume, whereas the second version picked out the few works that would be considered essential to Singer’s thinking and writing. The final version aimed to find a balance between the two extremes. Still, there are aspects of the first draft that were interesting in themselves – especially reviews, acceptance speeches, and other pieces of literary miscellania. Among them was a list: “Ten Reasons I Admire Henry Miller.” It appears here for the first time:

1) Henry Miller was a perfect egotist, which means he tried to be happy himself, never to make others unhappy.

2) He didn’t give a hoot about the critics. He never read them.

3) He never acknowledged Freud, Adler, Jung. As far as he was concerned the whole school of psychology never existed.

4) He never tried to solve a single sociological problem. As far as he was concerned this rotten world was good enough.

5) He never tried to find new ways or methods in literature. He wrote as he spoke – simply, clearly, without any pretension to style.

6) He never made the slightest effort to redeem humanity.

7) He kept away from all politicians.

8) He never preached anything, not even his own way of life.

9) He never complained, neither in life, nor in his writing.

10) He never strived for honors. Dishonor was good enough for him.

I was intrigued by this singular affirmation of a contemporaneous writer and so I searched his correspondence for letters from Miller. I found a few short letters, the first two dated January, 1965, in which Miller expresses his extreme enthusiasm for Singer’s work. “I finished Family Moskat the other night,” he writes, “feeling as if I had lived through 500 years of Jewish history, myth, legend, torture and humiliation. It was a real feast.” Miller, who was not Jewish, concludes his letter, “All I need to discover before I die is that little drop of Jewish blood in my veins.” And while I didn’t have access to Singer’s replies, I saw that they had a warm exchange and shared a sense of admiration for each other’s work. But I still didn’t understand where Singer’s list came from, and what had inspired him to compose these specific sentiments about Miller.

Then I came to a form letter sent from Miller to his colleagues, in which he asked for support in being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The letter asks the recipient to “write a few succinct lines” to the Swedish Academy and includes a PS: “If you are also vying for the prize, forget this and let me write one for you!” The letter is undated and the postmark is relatively faded, but you can make out the year as 1978, the same year that Singer received the Nobel.

A follow up letter, dated September 16, 1978, seems to reply to Singer’s own admission that he is, indeed, vying for the prize too. “I know it seems shameless but I know I deserve the prize… All my life I have had to fight for every crumb I received… So please forgive me! … I think you know that my heart is in the right place.” It’s a touching and vulnerable note that shows just how hard a writer whose influence on world literature today is unquestionable had to fight for a grain of recognition in his time. It was also written less than two years before Miller died in 1980.

Singer wrote out the list in his own handwriting. And, having found these few letters, I couldn’t escape the feeling that he’d written it after Miller’s death – perhaps out of a feeling of guilt for getting a prize that he believed Miller deserved too. But the Nobel Prize isn’t designed to be awarded to everyone who may be deserving. As Miller says in his letter, “it is a matter of politics,” and Singer served the politics of the moment, likely as the only Yiddish writer with the stature and renown to be awarded the prize. That didn’t mean Miller didn’t deserve it as well. But, at least from the traces Singer left behind, he seemed to acknowledge that there were other writers out there who were just as good – and who didn’t get the prize.

As a final note, apropos the Nobel Prize for Literature, people often call Singer the “only” Yiddish writer to receive a Nobel Prize. This, I believe, is a limited view of literature and history, and it’s not a view that reflects Singer’s own faith in the Yiddish language. So, when it comes up, I often say that Singer was the first Yiddish writer to win the Nobel Prize. Because, as Singer reminded his audiences, in Jewish history, the distance between dying and death can be very long.

David Stromberg, a writer, translator, and literary scholar, is editor for the Isaac Bashevis Singer Literary Trust. His books include Baddies, Idiot Love and the Elements of Intimacy, and A Short Inquiry into the End of the World.