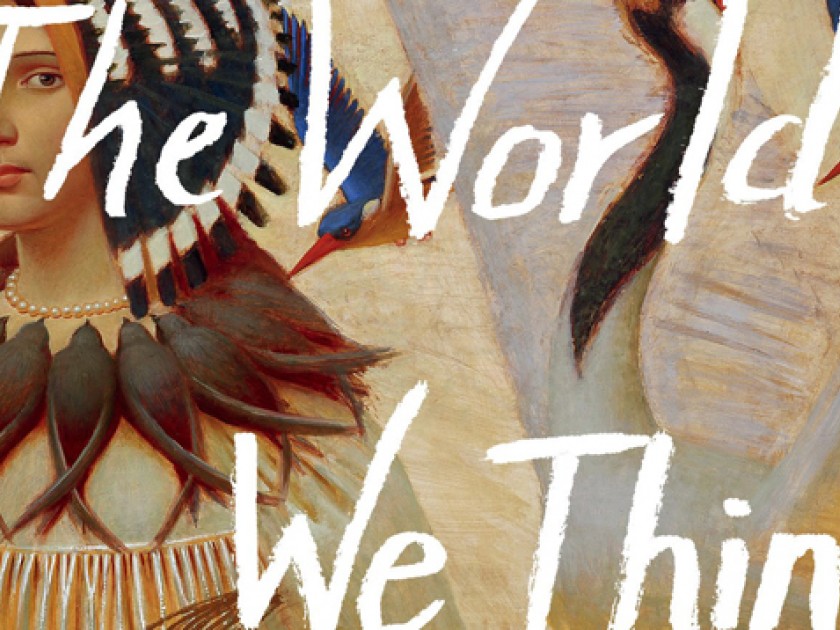

Dalia Rosenfeld, a graduate of the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop, moved to Israel two years ago to reinvent her life. And though she has been publishing sharply observed literary fiction in American journals and magazines for two decades, The Worlds We Think We Know (Milkweed Editions) is her first collection. The wait for these twenty new stories has been worth it.

Adam Rovner: The Worlds We Think We Know has already garnered praise from major American writers, including Adam Johnson, Cynthia Ozick, and Gary Shteyngart. Shteyngart has called your work “very funny, Jewish and wise.” Are you conscious of being a “Jewish writer?” What does that mean to you?

Dalia Rosenfeld: I wish I knew! I was hoping I was far enough removed from the immigrant experience to be unqualified to answer that question, but here I am, suddenly the holder of a second passport, a new immigrant to Israel. But that doesn’t help much either, because the days of linking “Jewish writer” to immigrant status are pretty much over now. If the question implies loyalty to a people, I feel that strongly outside the context of writing, but on the page my loyalty is to language. Jews owe their survival to the power of the written word — you can’t take your land with you into exile, but you can take your stories — which is not to suggest that focusing on language alone makes one a Jewish writer, but feeling at home in language constitutes a major part of the Jewish experience.

AR: Your prose certainly demonstrates that you feel at home in English, but can you really use a non-Jewish language to convey Jewish sensibility?

DR: I don’t know if such a thing as a “Jewish sensibility” exists. What I do know is that there are certain states of mind or being that I associate with Jews, and that my Jewish characters often possess. For one thing, they are conscious of a collective past, but rather than this past functioning as a unifying force, my characters find it hard to feel rooted in the present. It gives me great pleasure to reference the Jewish past because doing so connects me with what is familiar and offers a sense of comfort and continuity: a poppy seed cake burning in the oven, a Yiddish phrase, a story from the Torah that a bar mitzvah student couldn’t care less about. Maybe it’s this seeking a conversation with the past that makes one a Jewish writer?

AR: The collective past in the guise of the Holocaust appears in your title story and several other standouts. Can you speak about why the Holocaust’s long shadow enters your work?

DR: Until recently, the Holocaust shaped my identity more than any other chapter in Jewish history. My father is a Holocaust scholar, and I grew up in a house in which the entire living room was given over to books on this subject. While my friends were reading Jane Eyre, I was reading about the Jews of Vienna being forced to clean the sidewalks with toothbrushes. What’s interesting is that I never felt burdened by this history; haunted, yes. Absolutely. Because it wasn’t just the books: it was also listening to the stories of survivors who came to see my father. When you relive your own memories, it’s traumatic, but when you experience another person’s, it’s something abnormal, unsettling. And it’s those haunted echoes that appear in my stories, sometimes just with a single image, such as a survivor reusing a tea bag until it resembles a shriveled walnut. Since moving to Israel, my preoccupation with how Jews died has shifted somewhat to how they live.

AR: Who are some of the writers who help you understand how Jews lived yesterday and how they live today?

DR: A partial list in no particular order would include Israeli authors Yaakov Shabtai, Yoel Hoffman, A. B. Yehoshua; American writers Rivka Galchen, Cynthia Ozick, Bellow, Malamud, Nicole Krauss, Jamaica Kincaid; Europeans such as Bruno Schulz, Kafka, Leo Perutz — a now obscure Austrian novelist (not to be confused with Yiddish writer I. L. Peretz) — and both I. B. and I. J. Singer.

AR: I can see the affinity your collection has with many of these writers. What I mean is that your stories often depict a sense of displacement. Sometimes it’s geographic — Americans in Israel, Russians in America, cosmopolitans in small towns. Why are uprooted characters so common in your stories?

DR: I’m drawn to characters whose actions are informed by an inner logic they themselves are not aware of, and that is guided — as you put it — by a state of displacement, sometimes forced, sometimes self-imposed, in which fixed boundaries fall away to give the characters a chance to redefine themselves. But they often squander the opportunity by engaging in a series of missteps, or self-sabotage, such as in my story “Swan Street,” where Misha, the protagonist, moves to America only to end up in a kind of voluntary exile, avoiding situations that would allow him to settle into his adoptive homeland. At the end of a story, I always discover the same thing: that human behavior is inscrutable — but still fun to write about.

AR: That comedy of human inscrutability comes across in your stories, many of which possess a wry sense of humor. Is humor difficult for you to write?

DR: I honestly wasn’t aware of this wry humor people keep pointing out until they started pointing it out. There’s no doubt that it’s healthier to find the humor in horrible situations than to stew in your own juice — something that I tend to do in real life. One of the purposes humor serves is to highlight our vulnerabilities without being held hostage by them.

AR: Many of your characters are women who reveal their vulnerabilities while at the same time demonstrating resiliency. Are you conscious of writing resilient female characters?

DR: I think a lot of writing happens on an unconscious level. The craft part is a conscious thing, but what motivates the characters to do what they do — they’re just like us, acting on impulses, intuition, instinct, feelings, all those things that can’t be explained rationally but that ultimately make us human. While I don’t divide the world into male/female, I find it hard to argue with a phrase I recently came across describing men as “expressively economical” with their emotions. This implies that women are not — that women are something else. And it is this “something else” that makes it hard to speak the same language, to enter into a realm of closeness that both sides desire, but in different ways. The resilience of a character comes when the love she seeks isn’t within her grasp, but still she can find beauty in the world.

AR: Your characters often seem lonely to me. Is writing a lonely activity for you?

DR: No! Writing is an antidote to loneliness. It’s what connects me with the world and helps me understand it better. Especially since I write in cafes, and in Israel people never leave you alone. For the last week, the same man has come up to me every morning and said, “Did you change that part of your story I told you to change?” He had shared some Persian proverb with me months ago, which I liked but altered a bit, and he was of the conviction that I should leave it the way it has been for the last five hundred years. I probably shouldn’t have showed him what I did with the proverb, but at the time I wanted to thank him. This morning he abbreviated his question to a single word: “Nu?”

AR: Nu? So what are you working on now?

DR: I thought I was working on a novel called The Physics of Time Travel in which an American woman moves to Israel and imagines parallels between her personal life and the trajectory of her adopted country. When I read the first chapter, I realized it was a stand-alone story and my interest in the theme had been exhausted, but in a good way. In a way that allowed me to write a second story about something totally different, and without feeling guilty about it. I’m now fifty pages into a second collection called The Physics of Time Travel.