As our editors work on the second issue of Jewish Book Council’s literary journal, Paper Brigade, we present a tribute to the group of resistance fighters who provided the inspiration for our publication’s name.

“The paper brigade was our resistance — our way of defying the Nazis,” explained Dina Abramowicz, a member of a small group of Jews in the Vilna Ghetto who risked their lives, while working under Nazi surveillance, to secretly rescue and hide thousands of Jewish books and documents the Nazis were planning to ship to Germany.

Vilna (Vilnius), Lithuania was a treasure-trove for the Nazis. Once known as the “Jerusalem of Lithuania,” it was a vibrant Jewish cultural and religious center with 105 synagogues, thriving educational institutions, enormous libraries, and prominent intelligentsia.

In 1942 the Nazis ordered Herman Kruk, head of the Vilna Ghetto library, and Zelig Kalmanovich, a director of prewar YIVO, to collect the very best “Jewish books, artwork, and museum valuables” for shipment to Germany, where they were to be displayed — after the Jews of Europe were murdered.

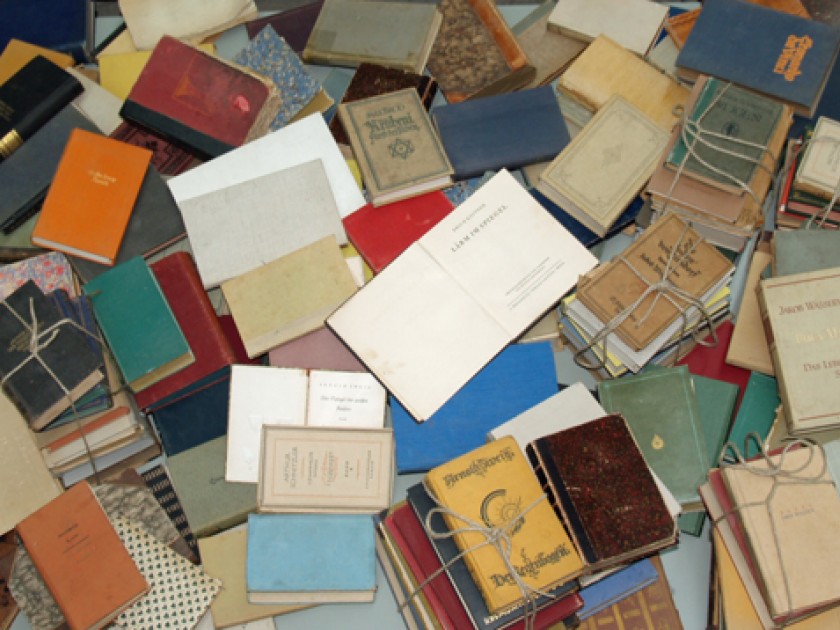

About a third of the books were to be preserved for the Germans; the rest were to be destroyed. When the Nazis carried out “a selection” of the books they wanted, they threw “70% of the books from the YIVO treasures into the trash as scrap paper.” Kruk wrote that “the Jewish workers employed on the project are literally weeping.… Your heart can break as you watch.”

Kruk recruited members of the Jewish intelligentsia to join his staff of forty men and women, including the Yiddish poets Abraham Sutzkever and Shmerke Kaczerginski, who became the leaders of the smuggling operations. Between March 1942 and September 1943, their “paper brigade” rescued thousands of books and tens of thousands of documents from Nazi hands.

The workers would typically hide the cherished books and papers and artifacts in their clothing and shoes — first to smuggle them out of the sorting building, and then to get past the police at the ghetto gates. If the Germans were on guard, they would confiscate everything and beat or shoot the offending Jews. But if Jewish policemen were on guard, they might allow the workers to pass because they were “only carrying papers.” (Thus the police dubbed them the “paper brigade.”)

Abraham Sutzkever (Photo: Fritz Cohen)

Abraham Sutzkever was the most ingenious rescuer of materials in the paper brigade, at one point obtaining a written permit to take wastepaper into the ghetto for use in his household oven. He then used the permit to bring in letters and manuscripts by Maxim Gorky, Sholem Aleichem, and Hayim Nachman Bialik; one of Theodore Herzl’s diaries; drawings by Marc Chagall; and a rare manuscript by the Vilna Gaon.

While some books and valuables were given to Polish or Lithuanian friends for safekeeping outside the ghetto, most were brought back to be hidden in the ghetto itself — in a concealed basement in the library and in underground bunkers spread throughout the ghetto. (For example, in October 1942 Kruk recorded 200 Torah scrolls in bunker #3.)

Although Kruk and Kalmanovich were not aware of it, about ten of the forty workers, including Sutzkever and Kaczerginski, were also members of the FPO, the ghetto’s underground Jewish fighting organization led by Abba Kovner. Along with the papers, they were also smuggling guns and ammunition into the ghetto for a planned revolt.

Sadly, in the end, most of the forty members of the paper brigade were murdered by the Germans, including Kruk and Kalmanovich. The only survivors were the paper brigade workers in the Jewish resistance — including Sutzkever, Kaczerginski, the fighter Rushka Korjak, and the librarian Dina Abramowicz (quoted earlier), all of whom escaped from the ghetto to join the Partisans.

In July 1944, they returned to Vilna with the Soviet Army and the Jewish partisan brigade and searched for the books they had hidden with a plan to use them as the foundation for a new Vilna Museum of the Jewish People. That story, and the story of how the documents were eventually reclaimed by YIVO — fifty years later — in New York, will be told in a forthcoming book by Professor David Fishman.

Lenore J. Weitzman is writing a book on the kashariyot, the young women who were secret couriers for the Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. She coedited Women in the Holocaust (Yale, 1999), a finalist for two National Jewish Book Awards, with Dalia Ofer.