“Joe on Cleopatra.” Image courtesy of the author.

My great Uncle, the writer and director Joseph L. Mankiewicz, died at the age of eighty-three in February 1993. I didn’t know him very well, although he lived not far from where I grew up in Greenwich Village. I met him only once or twice as a boy, and my memories were of a remote older man, shrouded — or so I thought — in the shame of having made what I’d been told was the biggest bomb in Hollywood history, Cleopatra. Still, when I met him as an adult for the first time a few years before he died, I was struck by our family resemblance. He was pudgy, sweet, and kind; he reminded me of my beloved Uncle Frank and my Mom. He seemed like a mensch.

Then, at his funeral, something struck me. The service was held in a church not far from Joe’s adopted home of Bedford, an hour north of New York City. Afterwards, trying to squeeze through the exit to the church amid the throng milling around, I very nearly knocked the openly mourning actor Hume Cronyn down the church steps. I suddenly realized something. “Wait a minute,” I said to my cousin Ben. “Aren’t we Jewish?’

It is a question that has reverberated around certain families for decades, especially those having anything to do with Hollywood.

The movie industry, as Neal Gabler’s seminal book How the Jews Invented Hollywood makes abundantly clear, was founded almost exclusively by Jews. They were men from the East Coast who had been furriers and haberdashers in their former lives but who moved into the nascent business as it grew in the early 1900’s, before they eventually moved the whole damn thing West for sunnier climes. It was a better life out there, and the men who ran the studios — men like Adolph Zucker, Louis B. Mayer, and the Warner Brothers — quickly realized the power of their new art form. They weren’t just making money (though they were, hand over fist); they were crafting the American mythology in a whole new way, in flickering light beams projected on large screens across the country.

They weren’t just making money; they were crafting the American mythology in a whole new way, in flickering light beams projected on large screens across the country.

It was heady stuff, and also dangerous; the men understood that the stories they told would have to be American with a capital A. Without exception, the studio heads became full-throated proponents of Mom, baseball, and apple pie. The movies would show immorality — everybody loves a villain, after all — but the righteous virtues would have to win out.

In fact, one of the early screenwriters laid out the basic Hollywood story rules in a letter to a pal back East; he told him that in the movies, the good guys had to win, the bad guys had to lose, and both the hero and heroine had to remain virgins. This stood in direct contrast with the villain, who, at least until the final reel, “can have as much fun as he wants — cheating and stealing, getting rich and whipping the servants.”

The writer of that letter was Joe’s older brother, my grandfather: Herman Mankiewicz.

In many ways, Herman was the exemplar of the Eastern writer who came out West to write for the movies. The first born child of a domineering, immigrant Jewish father from Germany (but “Pop was a rip-snorting atheist,” his boys later insisted), Herman became, in many ways, the prototypical self-loathing alcoholic: large-hearted, brilliant, hilarious, self-destructive, and completely convinced he was better than the industry he was helping create. Herman soon sent another missive back East, and this one, with the exception of Citizen Kane (which he co-wrote with Orson Welles), became perhaps his most well-known literary legacy; it was a telegram to his old friend, Ben Hecht, imploring him to join him out West:

“WILL YOU ACCEPT THREE HUNDRED PER WEEK TO WORK FOR PARAMOUNT PICTURES,” Herman wired. “THE THREE HUNDRED IS PEANUTS. MILLIONS ARE TO BE GRABBED OUT HERE AND YOUR ONLY COMPETITION IS IDIOTS.”

Then, most crucially, Herman added the kicker: “DON’T LET THIS GET AROUND.”

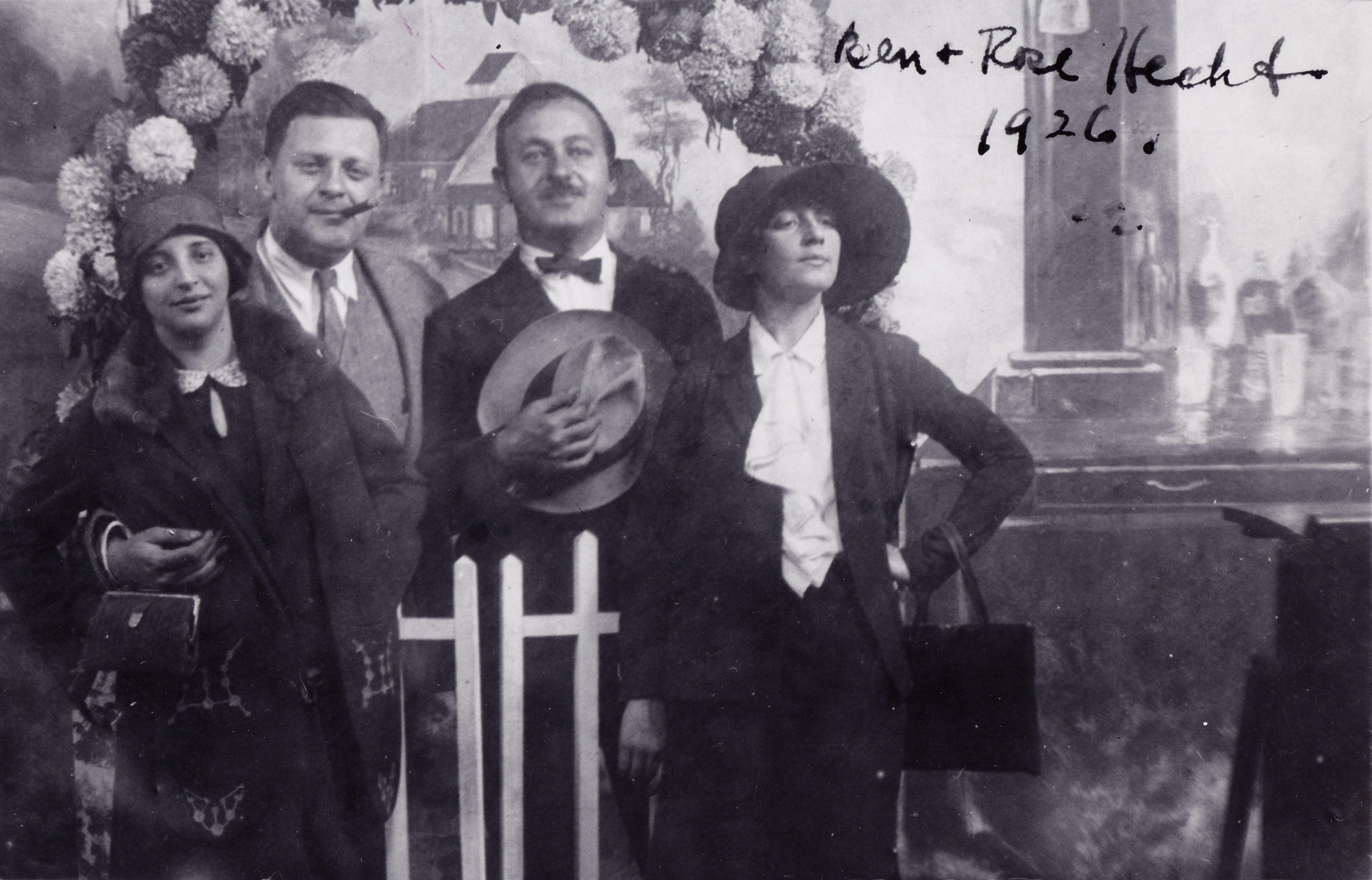

“The height of New York sophistication, Herman and Sara with Ben and Rose Hecht at Coney Island, 1926.”

The telegram started the flood. Before long, the studio lots were swamped with Eastern writers, playwrights, and novelists who understood — explicitly or implicitly — that movies were beneath their higher calling, but who found the easy money irresistible, and were only too willing to churn out the products that were transforming the nation’s self-image.

Because it was clear: the stories would bear no traces of the Jewish experience. The writers themselves, whether Jewish like my grandfather (and great-uncle) or Herman’s confreres Hecht or George S. Kaufmann, or non-Jews like Nunnaly Johnson and Charles MacArthur, were writing American stories now. In one mogul’s colorful phrase, the idea was to “hide the Jew.”

Thus it was that even as the storm clouds of Nazism gathered over Germany in the early 1930s, Hollywood mostly ignored it. The German-American movie fans could not be offended, and, more crucially, the German foreign markets were simply too lucrative to risk. So while Hollywood’s shores were swelling with émigrés from Nazi Germany, like Fritz Lang and Bertolt Brecht, the movie studios turned a blind eye to Hitler’s rise to power.

While Hollywood’s shores were swelling with émigrés from Nazi Germany, like Fritz Lang and Bertolt Brecht, the movie studios turned a blind eye to Hitler’s rise to power.

But my grandfather, non-conformist to the last, had other ideas. In 1933, he set about on a quixotic attempt to make a movie about the dangers of fascism, targeting the biggest idiot of them all: Adolf Hitler. Much in the way Charlie Chaplin did seven years later with The Great Dictator, Herman’s proposed movie, “The Mad Dog of Europe,” would tell the satirical story of a fictional dictator; he set the screenplay in Transylvania and changed the dictator’s name all the way to Adolf Mitler.

Herman spent years developing the idea, and even employed a rare strategy to try and mollify studios who might be loath to bite the German hand. He wrote the original idea as a play, then had his friend, the producer Sam Jaffe, option the material, the better to shield the studios from the idea that they had actually commissioned an original work attacking the Nazis. The screenplay itself was compelling, telling a haunting, prescient tale of two families riven by the horrors of fascism— “You’ve thrown away loyalty and love and honor,” one character tells another who has become a collaborator with the Nazis. “Every time he opens his mouth, he lies,” another character declaims of Mitler.

The screenplay is sound and solid, and reading it, it’s easy to imagine the movie that might have sprung from it — intelligent, biting, dramatic, and even wise.

But it was never made. The huge market in Germany for American films made such a picture not only unplayable in Germany, but unproduceable in America. Always skittish about their Jewishness, the studio heads knew that putting forth any such staunchly anti-Nazi film would only remind the movie-going public of the non-Christian nature of the men who ran the business. Assimilation was and would remain the cardinal rule for the machers, who were glad to have put their days as furriers, hat-makers, and upholsterers in the rear-view mirror.

And so Hollywood honchos rejected “The Mad Dog of Europe” in favor of maintaining the cooperative relationship they had with the German government. Moving from one producer to the other, and one studio to the next, Herman eventually tried all the larger independent production companies, but it was no use. Georg Gyssling, the German consul in Los Angeles and a Nazi, went so far as to threaten the Hays Office that if “The Mad Dog of Europe” were made, his government might ban all American films from showing in Germany. At one point the Nazis upped the ante, saying that if the film were produced, actual harm would come to the Jews in Germany. Finally, Joseph Breen, the moralizing Catholic who ran the voluntary motion picture code under which the studios operated, weighed in, declaring: “Because of the large number of Jews active in the motion picture industry in this country, the charge is certain to be made that the Jews, as a class, are behind an anti-Hitler picture and using the entertainment screen for their own personal propaganda purposes. The entire industry, because of this, is likely to be indicted for the action of a mere handful.”

The movie was doomed. Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM, laid it out explicitly: “We have a terrific income in Germany, and as far as I’m concerned, this picture will never be made.”

Herman never got over the irony: his attempt to reveal the truth about Nazi Germany was stopped by the Nazis in the United States, a land of supposed freedom and democracy.

The only thing to do, if one was a Jew who wanted to succeed in Hollywood, was to continue to play the game. In subsequent years, as my grandfather’s career, Citizen Kane notwithstanding, continued its gradual descent, he would see his brother’s star rise, and soon, Joe, nearly twelve years younger and a far more political animal, would eclipse him, becoming first a successful producer (The Philadelphia Story, Woman of the Year, etc.), then starting to direct, and soon ascending the top ladder of Hollywood’s pecking order by winning Academy Awards for Best Direction and Screenplay honors two years in a row, for A Letter to Three Wives and All About Eve. Herman took it all in ruefully.

Would he have been surprised to learn that his brother’s funeral would be held in a Church?

Nick Davis is a writer, director, and producer. His book Competing With Idiots: Herman and Joe Mankiewicz: A Dual Portrait, was recently published by Knopf, and his film about the 1986 Mets, Once Upon a Time in Queens, recently aired on ESPN and is now available on streaming platforms. He lives in New York City with his wife and two daughters.