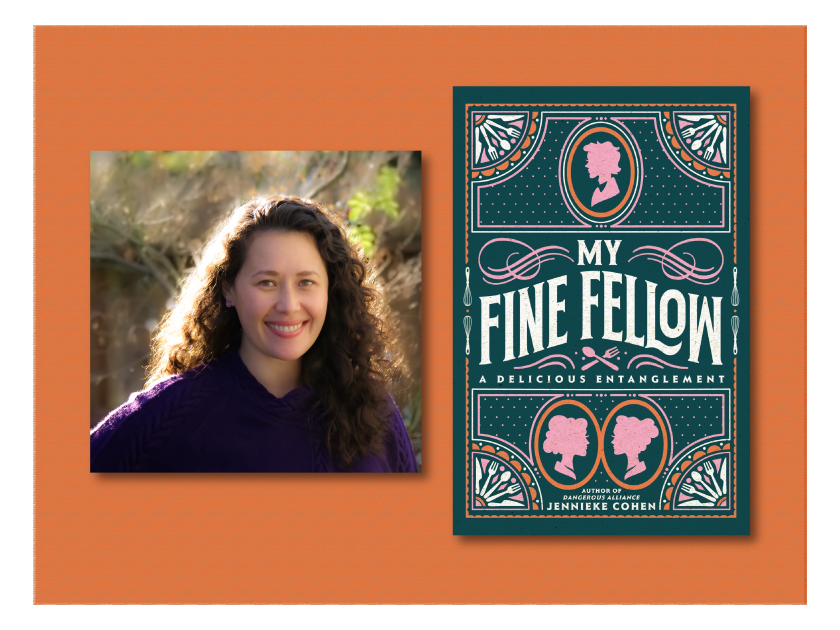

Author photo by Nasson Boroumand

Jennieke Cohen’s My Fine Fellow: A Delicious Entanglement was a 2023 Sydney Taylor Silver Medal winner in the young adult category. Emily Schneider spoke with the author about how she created this highly original work based on Pygmalion and My Fair Lady, including Jewish themes and characters. This interview is part of the Sydney Taylor Blog Award Tour. Find the full STBA blog tour schedule here.

Emily Schneider: I’m very pleased to be able to speak with you about My Fine Fellow. I’m sure our readers know that a popular trend in young adult literature is modernized versions of classic books, including Anne of Green Gables, Little Women, and The Secret Garden, usually with updated language and focusing on an exploration of contemporary issues. My Fine Fellow is a bit different. It’s based on George Bernard Shaw’s play, Pygmalion and the musical My Fair Lady. You set it in an earlier era, and introduce a central Jewish character along with the theme of antisemitism. What inspired you to write this truly original novel?

Jennieke Cohen: Well, thank you. I’ve always loved My Fair Lady, and I eventually started looking at the source material, Pygmalion, and some of Shaw’s other plays as well. And because My Fair Lady is one of my favorite musicals, I thought nobody had really done this. No one had redone it, at least not in the way that I envisioned. I thought I could do this in a totally different way. I could set it in a time period that’s not the original one, but not contemporize it either. I was also reading a book called The Jews of Georgian England by Tom M. Endelman, and I thought, why don’t I set it during the 1830s, and why don’t I figure out a way to have a Jewish character?

Because being a Jew, I really wanted to talk about my experience, although, obviously, the 1830s is not my era. However, I thought it would be a good time period for the book; it’s not used very often in YA literature. All of these factors combined, and then I decided I wanted to gender swap it as well so that I could have the girls be the ones with agency, the ones to teach this boy, Elijah Little, how to become a gentleman chef, as I do in the book.

ES: You begin with a relatively obscure counterfactual of history. The book’s premise is that Princess Charlotte, daughter of George IV, survived and became Queen. In that case, Queen Victoria and the royal family of today would not necessarily have inherited the throne.

JC: I didn’t want to write another Victorian novel where the women were put upon. Even in Regency novels, that’s often the case. And so I thought, is there a way that I can deviate from history? I picked this specific point where the timeline could split. Because the death of the popular Princess Charlotte was such a huge event, something we as Americans don’t generally know or care about, it gave me license to create a new world. It was also a way to give the girls more agency, as well as a better basis to have more diversity in the book, which was important to me.

ES: Do readers who bring knowledge of the sources or the history have a different experience reading the novel?

JC: Readers familiar with My Fair Lady and Pygmalion get some in-jokes, but most readers who relate to the book have not actually brought that prior knowledge to it. I do hope that it might pique their interest in watching the musical or reading the play.

ES: Speaking of the sources, Helena Higgins and Penelope Pickering are loosely modeled on Shaw’s characters and on their counterparts from My Fair Lady, but you haven’t only changed their gender, you’ve made their personalities somewhat different as well.

JC: Helena is based on Henry Higgins. She’s related to his archetype, but she does also have to deviate from it. She can’t just be him as a woman, that would be ridiculous. There are class dynamics at play as well as gender in the way that she treats Elijah. She’s in the aristocratic class, and Penelope is from the gentry. And then, of course, Elijah’s a member of the lower classes.

Penelope is obviously based on Colonel Pickering, who is very much a yes-man to Henry Higgins in the original. I wanted Penelope to be her own person, the type of girl who’s happy to get along, but when something that she feels strongly about really gets to her, she will stand up and say, “this is wrong.”

ES: Another way that the book stands apart from the trend is in your use of language. Most updated versions of classics, by definition, use modernized language. Instead, you have an ongoing dialogue with Shaw’s language. Sometimes you quote him directly. Sometimes you allude to the play or the musical, in a way that’s funny or sometimes critical. That had to be one of the most challenging parts of writing the book.

JC: It actually seemed to come pretty easily – it was fun! I was pulling in pieces from the original, then turning them on their head a little bit, and throwing in some modern sensibilities, while still trying to keep the language of that era. I was reading a lot of British literature, but at the same time listening to audio of Wilkie Collins’ novels, and those by other Victorians. All of that percolated in my brain. And I wanted to have an omniscient narrator too, as they do in many Victorian novels.

And so I thought, is there a way that I can deviate from history? I picked this specific point where the timeline could split.

ES: The characters are so distinctive in the book. Elijah Little is modeled on Eliza Doolittle in the original. I find him to be one of the most interesting Jewish male characters in YA fiction. Tell us how you came up with the idea to make him Jewish, and to combine his identity with his class background.

JC: Initially I thought I was going to have him be the archetype for my family, my ancestors who came from Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus. And then, when I did more research, I realized these immigrants didn’t usually travel to Britain at this time period. I had to invent a different backstory for him, which was perfectly fine because it made him his own person, not just an homage to my family. I took a lot from my research into what Jews in that time period would have dealt with, how they would have lived; that’s the one aspect of the book that is as close to historically accurate as possible. Clearly, we’ve been dealing with prejudice forever. But Elijah evolved into his own character. I had to go back in and fill out more scenes that would contribute to that, like his scene with the tailor.

ES: Mr. Benjamin is the old Jewish tailor who fits Elijah for the elegant clothes he will need to appear in society. He is one of my favorite characters, and he represents the opposite end of the age spectrum. That was a terrific scene.

JC: It was actually a tough scene because I wanted to get it right. Mr. Benjamin couldn’t be a caricature of a tailor from the 1830s. He had to be somebody real, and a great way to get a glimpse of Elijah’s parents – who had died – and also bring in a totally different successful type of Jewish man rather than who Elijah was going to end up being. Mr. Benjamin may not attain that level, but he is successful nonetheless and happy with his life. I remember as I was finishing writing that scene, I was crying a bit as I was writing it, partly because of its father-son dynamics.

ES: Another departure from the original sources is the relationship between men and women. We talk about the objectifying male gaze, but in your novel you replace that with a female gaze. Penelope is attracted to Elijah. She definitely looks at him with fascination, but also respect.

JC: It was important for me to have them end up as equals, not as mentor and student. The romantic tension between Henry Higgins and Eliza Doolittle is unequal, and not ideal for me personally. In the original, Colonel Pickering was always much more of a gentleman toward Eliza than Henry Higgins was. I chose to take that further and have them end up having a real relationship and a real understanding of the minds.

ES: Elijah is Jewish, and Penelope’s background also marginalizes her within English society and forces her to be secretive about her identity. Could you speak to that?There’s a major focus on Jewish themes in the book, but there are also explorations of other kinds of racism and prejudice that encroach on people’s lives.

JC: I made Penelope Filipina and British, and I’m also half Filipina. It was important for me to include that in the book authentically. Because she is not white, she does not exactly hide who she is, but her parents have sent her to England to be able to be successful and to do what she wants with her life. They stay away to protect her identity, and she’s in England all on her own, figuring out how to be an adult. Helena, meanwhile, and everyone else who she lives near and associates with, just assume that she’s Caucasian. Penelope doesn’t want to deny who she is, but she also wants to avoid the consequences of racism. I did want to bring in the entire continuum of racism and prejudice. Helena, a character who develops throughout the book, doesn’t quite get it, and she has to wrap her head around what it means to have friends who are not the same as everybody else.

ES: Feminism is at the novel’s core. Readers might check Wikipedia to look up the Freedom of Female Education Bill that is referred to several times, but you invented it! It’s part of the book’s counterfactual element.

JC: I had to create this good reason for women to be able to have professions. Society does not change overnight; just the change of a monarch would not enable women to have different professions. I created a more concrete reason for it in the education bill, meaning that girls could be educated in careers that had been historically restricted to men. The changed timeline gave me the license to do that.

ES: The career you emphasize is the culinary arts. Your discussions of food in the book are highly detailed, but instead of validating snobbery about food, you democratize the art of cooking, emphasizing its multiculturalism. Every character has a specific relationship to food. You describe one of Elijah’s creations as “a stuffed bread in the shape of a round parcel filled with pickled beef, caraway, and cabbage, and topped with caramelized onions.” The reference to the humble bread shaped like a parcel is as important as the list of delicious ingredients.

JC: I’ve been immersed in cooking since I was a child. I would watch PBS and write down recipes from the TV shows, and then I’d try to recreate them, sometimes more successfully than other times. With the rise of the Food Network and British cooking shows, everything became more available. I really have grown up traveling with my parents, eating foods from all different cultures, and I wanted to showcase that in the book. So many foods and other traditions overlap. I had to do some deep dives in coming up with Elijah’s dishes.

ES: Your characters are not always optimistic about that embrace of differences. Elijah is often discouraged. Your narrator captures the cynicism of a Jewish man who is constantly aware of prejudice: “He still believed more people existed in the world who didn’t ask questions, not because they didn’t know to ask them. No, they didn’t ask because they only wanted the answers they created in their minds.” At the end of My Fine Fellow, do you think readers will share Elijah’s pessimism?

JC: This was a book that had to end happily. But I don’t think Elijah believes that all the prejudice has gone away, and I don’t think the reader should think that either. He’s only one person; maybe his life and Mr. Benjamin’s are good, but there are many other people whose lives have not improved. Maybe Elijah’s successes at the end of the book could be the first step, leading to something more for other people as well.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.